Second Life for Hangar One

The Moffett Field landmark may yet house aircraft again.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/HangarOne-1.jpg)

Last December, H211 LLC, a company owned by three Google executives, offered to foot $33 million for restoring Hangar One, located on NASA’s Ames Research Center campus in California: in exchange, the company wants space in the hangar to park private aircraft owned by Google’s Sergei Brin, Larry Page, and Eric Schmidt. The proposal, says H211 director of operations Ken Ambrose, would reserve some of the hangar’s space for a museum or other educational facilities. But the offer, Ambrose says, has been met with nothing but “puzzling silence” from the space agency.

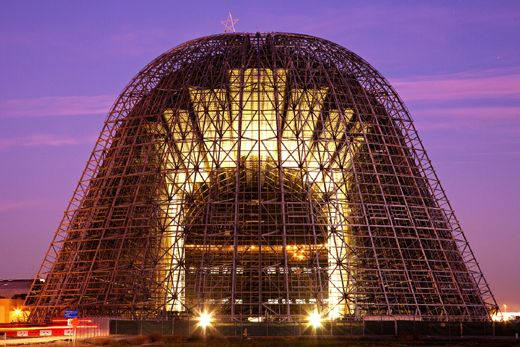

Built in the 1930s at what was then the Navy’s Moffett airfield, Hangar One housed the USS Macon. At the time, the hangar had the longest span of any building ever constructed, says Keith Venter, Ames’ historic preservation officer. “It’s 300,000 square feet of column-free space, which is enormous,” he says. “You could fit three Titanic ships side by side inside.”

The Macon was lost in a storm in 1935, and its sibling, the Akron, went down in 1933. The 1937 Hindenburg fire spelled the end of the great dirigibles. The hangar later housed smaller blimps and surveillance aircraft. (In 1994, the Navy turned Moffett Field over to Ames.) But for those who grew up in the hangar’s shadow, it remains a symbol of engineering prowess. “They built this with slide rules and tables, not with computers and all the materials we have today,” says Lenny Siegel, a founder of the Save Hangar One Committee.

In 1997, the Navy discovered the hangar’s siding was leaching polychlorinated biphenyls. It was declared a toxic site and closed in 2002. The Navy considered demolition, or turning the roof into a solar array. But historic preservationists rallied around it as an architectural gem in the Streamline Moderne style. Ultimately, rehabilitation was deemed cheaper than demolition. The work was divvied up between the Navy, which began removing the hangar’s contaminated skin last year, and NASA, which is responsible for the building’s re-use and re-siding.

In 2011, NASA proposed spending $32.8 million to re-side the hangar, but the NASA inspector general’s office concluded that since the agency had not identified a use for the hangar, the project wasn’t a fit for NASA’s facility construction funds.

Although the question of how to pay for re-siding the hangar remained, the rehab continued. By last January, the deskinning was at the midway point, with workers coating the stainless steel skeleton with an epoxy to prevent further environmental contamination.

Local Congress members have embraced the H211 proposal. So has the community, says Siegel, especially the idea of public-use space. “No one questions that the top executives of Google have the money to do whatever it takes to make the hangar usable,” he says.

At the February briefing announcing NASA’s 2013 budget proposal, which gave no clue as to the hangar’s fate, Ames center director Pete Worden promised that an answer is in the offing, saying that “NASA is delighted by private industry willing to do things that preserve and expand our aerospace infrastructure.” But, he said, there’s still an administrative process to complete.

Until then, hangar fans fret that if negotiations fall through and the hangar remains half-naked, the epoxy won’t last forever. Even the hangar itself seems anxious, if you believe the @MoffettHangar1 Twitter account, through which it complains of its fear of rain: “I dreamt I was bathing in a large vat of Rust-Oleum” and “I don’t have a better half. Just a wetter half.”