Scramble!

NATO’s Baltic Air Policing mission calls on an age-old combination of quick reaction and hot jets.

:focal(2500x911:2501x912)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/04/7a/047ad8cb-686f-4537-b4e3-e08650e0f15e/09j_fm2019_opener_live.jpg)

The sky over Lithuania was pale blue, the forest surrounding the air field deep green, and the armed Spanish air force Eurofighter Typhoon light gray. When the jet reached the end of the runway, it turned and paused, its insect-sharp nose and stubby canards dipping slightly. Suddenly its two engines, afterburners lit, kicked it into the air. A wingman followed seconds later, and the two Spanish fighters quickly faded into distant dots, headed north. What I had witnessed that summer day in 2017—beginning only eight minutes earlier when a Klaxon alert flushed two pilots from the ready room—is a standing ritual in air forces around the world. When deployed to the Baltics, responsible for guarding NATO’s eastern flank, each scramble needs to be perfect.

In NATO military parlance, it’s a Quick Reaction Alert, or QRA. The U.S. Department of Defense prefers Airspace Control Alert (ACA), but informally almost everyone calls it a “scramble.”

The Spanish Eurofighters that afternoon were on a training mission, a “T-scramble.” A real-world interception is called an “alpha-scramble.” By any name, QRA means armed fighters and crews standing ready 24/7 to launch within minutes to intercept unidentified aircraft approaching sovereign airspace without a flight plan or a squawking radar identification transponder.

Peacetime QRA is low-glamor police work to a fighter pilot, but virtually every nation with sufficient resources keeps fighters on alert, from the United Kingdom’s brand-new Typhoons to Cuba’s ancient MiGs. Fighters in the continental United States stand ready at 14 U.S. airports in places like Homestead, Florida; Chicopee, Massachusetts; and Portland, Oregon. Canada, which shares the North American Air Defense (NORAD) mission with the United States, adds at least two more. Not far from where we were standing in Lithuania, fighters were certainly standing QRA for the Russian Federation.

The Spanish fighters were in Lithuania last summer on a rotating NATO detachment near the small city of Šiauliai (show-lee), on a four-month deployment in the alliance’s Baltic Air Policing (BAP) program. NATO sends fighter detachments to Šiauliai because Lithuania, Latvia, and Estonia—which all joined NATO in 2004—are too small to afford their own advanced fighters for QRA. Looming large to the east of the Baltic states is Russia, with its large and capable military. The Soviet Union annexed all three Baltic nations during World War II and released them only when it broke apart in 1991. Russia’s 2014 annexation of Crimea has made NATO jittery about the three small Baltic allies.

A number of other air forces fly QRA missions in the area. South and west of Šiauliai, Danish and Polish F-16s protect their respective countries, integrated into NATO’s command structure. To the north, formally neutral nations Sweden and Finland guard their own airspace.

The Baltic Air Policing arrangement is unusual but not unprecedented: NATO also rotates fighters to Iceland (which doesn’t have a military), and the airspace of Albania, Slovenia, Montenegro, and Luxembourg are all secured by larger neighbors. In 2014, concerned over Russia’s activities in Ukraine, NATO added deployments to Ämari in Estonia and to Romania’s Mihail Kogalniceanu Airport. When I visited Šiauliai, the base hosted two detachments, six Spanish Tranche 2 Typhoons and four Portuguese air force F-16AMs. To the north, the French air force was at Ämari with four Mirage 2000-5Fs.

* * *

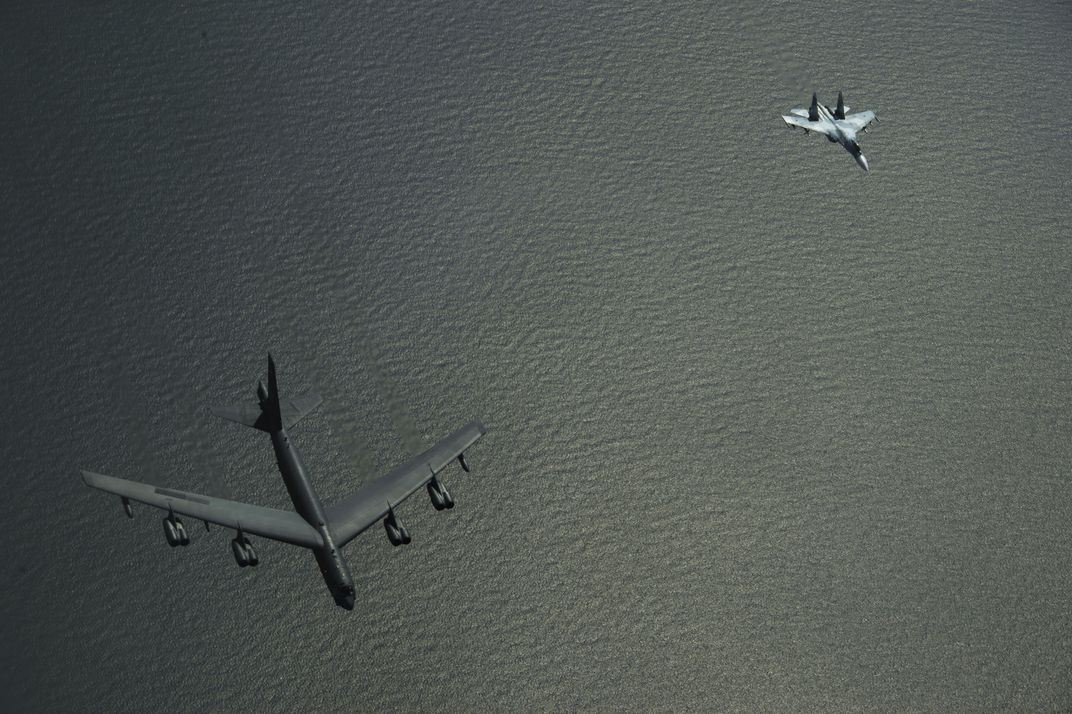

The deployments may be signals to Russia, but nobody wants to inflame tensions. Everyone I talked with—the Spanish air force officers, their Portuguese air force counterparts standing QRA at the other end of Šiauliai’s runway, the Lithuanian air force personnel who run and secure the base, the NATO spokesman in Germany—agree on one major point: BAP is about keeping the peace, not preparing for war. The QRA fighters are armed, but their mission is to chase, identify, and escort airplanes that aren’t communicating with air traffic controllers. So-called “non-squawkers” can be a menace unless escorted, like a car on the highway at night without lights on, so QRA pilots are launched to verify that they’re staying away. The BAP pilots earn the bulk of their pay intercepting Russian military airplanes, which routinely fly between the motherland and Kaliningrad, a heavily militarized Russian enclave wedged between southern Lithuania and northern Poland. Even with transponders off, such flights are perfectly legal, and the Russians fully expect NATO to investigate unidentified radar blips, just as they intercept aircraft near their own shores (which, not infrequently, are NATO intelligence-gathering flights).

* * *

Scrambling to intercept non-squawking Russians is part of the routine, says Lieutenant Colonel João “Sedi” Rosa, who commanded the Portuguese air force’s detachment of F-16s. “There are whole weeks without an interception scramble and then there are weeks when we scramble a lot of times. We are the reactors. It all depends on the action of the others. We are used to this. This type of mission doesn’t change.”

In other words, this mission isn’t much different from what BAP pilots do at home, policing the skies over their own nations. Rosa remembers one special scramble back home to follow a Russian Tu-95 Bear as it cruised down the Portuguese coast sniffing for electronic signals, but for the colonel, BAP means a break from the usual cast of QRA interceptees in Portuguese air space: lost general aviation pilots, crews with medical problems, and low-and-slow drug runners.

Aerial drug runners are rare birds over the Baltic. As “a fairly sensitive area,” Rosa says, Baltic airspace is intensely monitored. In addition to rotating BAP detachments, a no-squawk aircraft on the wrong track can pass under scrutiny by the Swedes, Finns, Poles, Danes, or Russians. NATO nations’ responses are handled by the Combined Air Operations Center (CAOC) in Uedem, Germany, which tells the Baltic Air Policing interceptors when to take off and where to go. “They have the big picture. This is not a pilot-controlled mission,” Rosa emphasizes. “The pilots are the eyes and the CAOC are the generals. We are given a heading and altitude by the ground controller.” The pilot’s job is to find the mysterious “track,” identify it, and report back. What they have seen over the Baltic, says Rosa, is every type of airplane in Russia’s military inventory, from transports to spyplanes to fighters.

“We are not planning to shoot,” says U.S. Air Force Lieutenant Colonel Clint Guenther, who flew on the most recent U.S. rotation to Šiauliai, from August 30, 2017 to January 8, 2018. “We’re there to identify and report, but we do scramble fully armed with air-to-air missiles.” Guenther’s BAP detachment was drawn from F-15Cs of the 493rd Fighter Squadron, ordinarily based at RAF Lakenheath in eastern England. Deploying on the mission requires a commitment of four combat-ready interceptors, two ready to go and two in reserve at all times, with their pilots and maintainers on steady alert under a temporary “transfer of authority” to NATO command.

“We’re there to defend the sovereign skies,” Guenther continues, “to make sure that the aircraft is telling [civilian air traffic control] where they are supposed to be and where they are supposed to be going.” When a pilot gets an alpha-scramble alert, Guenther concedes, “it is a super adrenaline rush. We train all the time but nothing can really replace the experience of actually intercepting a no-kidding foreign aircraft, whether it’s a civilian or military aircraft.

“From the horn going off to us taking off is normally less than about eight minutes, and that’s from anywhere in the QRA facility. Sometimes it’s as quick as five minutes depending on where we’re at. Then it’s a mad rush to go, find the aircraft, and get our systems all set up. Get the camera set up in the cockpit so we are able to film or take pictures or whatever we need to identify the target of interest.”

During their block on the BAP mission, the 493rd made 30 alpha-scrambles and “interrogated” 70 Russian military aircraft. “We saw all kinds of aircraft from [intelligence, surveillance, reconnaissance]assets to cargo aircraft to commercial aircraft, fighters, bombers—we saw it all,” says Guenther. “There were times we were intercepting aircraft going 170 knots and other times we were going 350 knots.” The interceptors must try to close to within 300-500 feet to snap clear photographs of the aircraft’s identification numbers, Guenther explains. “But normally it’s a pretty benign environment where aircraft are going straight and level.” Both Russia and NATO generally object to such intercepts but characterize them as “professional.”

Scrambling today might be routine and somewhat friendly, but it was forged in the fire that was the Battle of Britain. You know the scene: Very young men in tailored Royal Air Force uniforms and life vests lounge around, awaiting the alert bell to dash to their Spitfires and climb to death or glory. Unlike so many of the myths that follow war, this one is true. The RAF did invent scrambling—or at least the vocabulary.

Arguably, the founding father of the scramble was RAF Air Marshall Hugh Dowding, who assembled his defensive fighters into a nick-of-time air defense system. The Dowding System (which was never called that in his time) had three legs: a new radio direction-finding technology called radar, an underground control center to collate and analyze reports of incoming enemies, and QRA fighters under direct radio control. Starting in 1936, this experimental air defense system was put through its paces with a series of trial interceptions at RAF Biggin Hill and—to the surprise of many—it worked. By 1937, the network was refined such that the slow, obsolete Gloster Gauntlet biplanes used in the test were able to intercept mock-intruders 85 percent of the time. The system required a standard radio code vocabulary, and the RAF quickly created one that included the words “vector” for direction, “angels” for altitude, and “scramble” for, well, for scrambling. Over the next two years, the United Kingdom built “Chain Home” radar stations at a feverish pace, connected them to RAF Fighter Command via protected underground phone lines, and constructed a force of modern Spitfire and Hurricane fighters. The Dowding System was declared operational shortly before the formal outbreak of World War II, and though it had issues (dumping too much information on pilots, for example) it was just in time to hold off sustained attacks by the fearsome Luftwaffe.

Dowding may have formalized the scramble, but the roots of QRA go back to the interwar politics of airpower. During the 1930s, Claire Chennault was the leading U.S. Army Air Corps proponent for pursuit pilots against the then-dominant “bomber boys,” spearheaded by Billy Mitchell. The bomber will always get through, said the bomber boys, so the only practical defense was a strategic bomber offense so tremendous that the enemy could not respond. Chennault loudly disagreed. If the United States could build a force of modern interceptors, he argued, they could blunt any bomber offensive, and key to that defense was not to waste fuel, aircraft, or pilot morale on endless air patrols. Chennault held that interceptors should be kept ready on the ground, to be launched only after a network of observation posts reported an approaching enemy, and he proved the effectiveness of his theory with the Flying Tigers.

QRA collapsed virtually overnight at the end of World War II as the Allies reaped the peace dividend. U.S. Army Air Corps personnel fell from 2,250,000 in 1945 to 300,000 by early 1947. But air defense systems were revived as tensions grew between the Western allies and the Soviet Union. In 1949 the Soviets set off their first atomic bomb and deployed the Tupolev Tu-4, a reverse-engineered copy of the long-range, high-flying B-29. An international arms race began in earnest, and 1952 saw the unveiling of the massive Tupolev Tu-95, the nuclear-capable Bear that still keeps air forces awake at night. The second great age of QRA had begun.

The thought of Russian bombers and airborne armies crossing over the Arctic Circle touched off a near-panic in Washington. Suddenly newly formed squadrons were sitting QRA in brand-new jet interceptors. Improved radar systems were rushed to far-flung corners of North America, and soldiers in Alaska prepared for imminent conflict. “They Guard Our Arctic Frontier Against the Reds,” the Saturday Evening Post reported in September 1950. “Fighter planes scramble aloft, antiaircraft guns rake their muzzles belligerently towards the sky while on the ground, a host of cooks, cobblers and typewriting soldiers of sundry clerkly skills clap on steel helmets and scurry to the perimeter defenses to add the strength of their carbines to the strength of ground forces.” The United States and Canada agreed in 1957 on a joint air defense command, NORAD. Cold war QRA reached a new level in the late 1950s and early 1960s as the U.S. Air Force deployed its “century series” of interceptors (including the blazingly fast F-104 Starfighter), designed not as agile dogfighters but as supersonic weapon-system carriers.

The scrambles of that era were not all sweetness and courtesy. Both NATO and the Soviets deliberately overflew one another’s territory, photographing military installations and cataloging electronic signals. They forced defenders to scramble their QRA assets and turn on their most advanced radars then watched how quickly and forcefully the other could scramble. This game of aerial chicken could be deadly, and one of the earliest shoot-downs took place over the Baltic. In April 1950, Soviet fighters shot down a U.S. Navy PB4Y Privateer surveillance plane, which may or may not have been inside Soviet (what is now Latvian) airspace. All 10 crew members were killed.

Over time, changes in the technology and strategy of nuclear warfare—notably intercontinental ballistic missiles (ICBMs) and sophisticated surface-to-air missiles (SAMs)—eroded the dependence on interceptors. Missiles, satellites, and exotic electronics became the frontline guardians of American skies. By the time the Soviet Union collapsed in 1991 and the Open Skies Treaty was signed in 1992, ending tit-for-tat spyplane stalking, a lot of the steam (and the budget) had already gone out of the U.S. QRA commitment. The number of U.S. and Canadian interceptors assigned to NORAD fell from 750 in 1969 to 200 in 1990. In 1991, the U.S. Air Force deactivated its last active-duty stateside interceptor squadron and turned the responsibility over to the Air National Guard. Budget cutters further reduced the number of interceptor ANG units. On the morning of September 11, 2001, there were only 14 fighters ready to protect the continental United States.

* * *

Whether a different QRA system could have parried the 9/11 attacks is impossible to say, but the horrors of the day galvanized governments worldwide to reassert their aerial borders. Non-squawking airliners are now serious business. In March 2018, for example, a pair of Italian air force Typhoons went supersonic over northern Italy to overtake a non-responsive Air France Boeing 777. The interceptors reestablished radio contact with the airliner near the French-Italian border but forced it to make a 360-degree circle over the Alps to demonstrate that the crew had control, not hijackers. (Not everyone got the same memo. In 2014 Italian and French fighters escorted a hijacked Ethiopian airliner to a safe landing in Geneva, Switzerland, because the Swiss air force didn’t stand alert outside business hours, instead relying on agreements with Italy and France. The Swiss now stand alert every day during daylight hours, with the aim of a 24/7 alert by 2020.)

American QRA intercepts are common, though usually little-noted. In August 2018, NORAD reported that in the time since the 9/11 attacks, U.S. and Canadian jets conducted more than 1,800 intercepts of non-military aircraft. The statement came after NORAD scrambled two F-15Cs from Portland, Oregon to intercept a ground service agent who stole a Bombardier Q400 turboprop airliner from Seattle-Tacoma International Airport. The F-15s caught up to him within minutes of his unauthorized takeoff. The apparently suicidal pilot performed aerobatics over southern Puget Sound for nearly an hour, with the F-15s circling nearby. But they could do nothing when the airliner rolled over and crashed on lightly populated Ketron Island, killing only the pilot.

Back in the Baltics, the BAP mission remains peacekeeping, but the Baltic is a crowded neighborhood and the neighbors are heavily armed. It is not a good place to be nervous. The importance of “peaceful routine” became starkly clear seven weeks after I left Lithuania, when, during a training mission over Estonia with two French Mirage 2000s from the Ämari BAP detachment, a Spanish air force Eurofighter from Šiauliai accidentally fired an AIM-120 AMRAAM air-to-air missile. Fortunately, the missile didn’t strike another aircraft. Unfortunately, the missile disappeared over a nature preserve in central Estonia, where searchers were unable to find it despite an exhaustive 10-day search with helicopters, ground troops, and drones.

The accident became an international incident. The Spanish fighter detachment immediately stood down from operations, pending an investigation by the Spanish Ministry of Defense. The Estonian Defense Minister temporarily shut down NATO air exercises over Estonia. The Russian Ministry of Defense denounced the incident as further evidence that NATO’s presence in the Baltic was a threat to regional security.

At the end of August, new NATO detachments arrived for the Baltic Air Policing mission: Belgian air force F-16s flew into Šiauliai, and German air force Eurofighters replaced the French at Ämari. The Spanish detachment returned home to face the music. Today, Baltic Air Policing is flown by the Germans (who prefer two deployments back to back) with their Eurofighters, and the Polish air force with F-16s.

Perhaps QRA is more like police work than anyone imagines; most of us never notice police cars until we can’t find one. I remembered the day I took the train from Šiauliai back to Vilnius, the Lithuanian capital, to catch my airplane ride home. Lithuanian passenger trains are decorated with a giant stylized version of the national symbol, the Vytis, a medieval knight on horseback brandishing a sword over his head. Lithuania had to fight for its existence repeatedly in the 20th century, having been invaded by the Poles, the Soviet Union, Nazi Germany, and then the Soviets again. Now, under NATO’s protective umbrella, the nation can breathe a little easier. Waiting for the train at Šiauliai, I heard aircraft roar overhead. It was a pair of Eurofighters gliding down to land at the air base a few kilometers to the west. No one looked up aside from young children and a visiting journalist who wondered if flying QRA was the dullest duty imaginable for a fighter pilot. Except when it isn’t.