No Longer Afraid of the Dark

The civil engineering project that got the airmail through the night.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/8d/c2/8dc20ddd-a12b-4133-90c7-e593ecb24af8/night_nasm-nasm-9a06394.jpg)

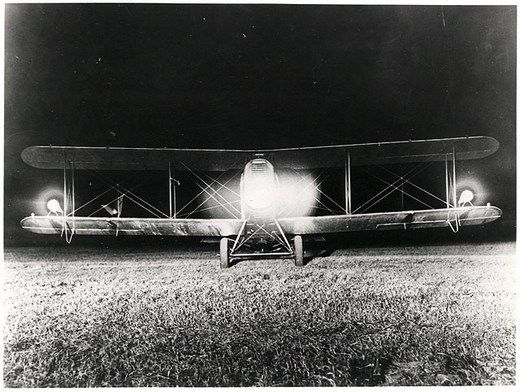

Some early airmail pilots feared they would become disoriented on night flights and lose control of their aircraft, just as some had lost their way when they flew through clouds. Others, having been given airplanes they considered unsafe and instruments that often didn’t work, doubted that management would light the way adequately. But in February 1923, several pilots volunteered for an experimental project to fly from North Platte, Nebraska, to an emergency field 25 miles away—at night.

It had been done before. Jack Knight famously flew the mail all night in 1921, but his achievement was a single demonstration proving that it could be done once, not the forerunner of a scheduled service requiring a corps of trained pilots, new instruments in airplanes, and expensive infrastructure on the ground. Before that service could begin, post office engineers lit an airway between Chicago and Cheyenne, an 885-mile flatland stretch of the transcontinental route. There on the prairie, the engineers wouldn’t face the expense of clearing landing fields on rugged mountainsides.

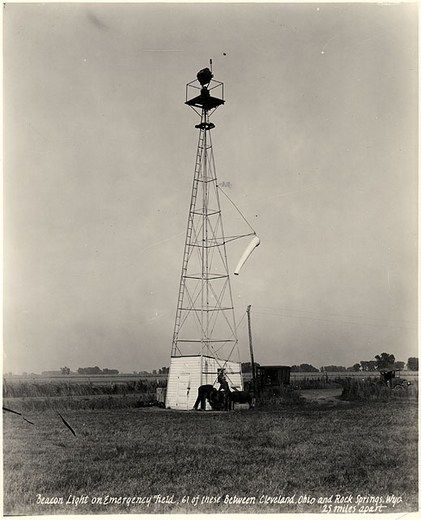

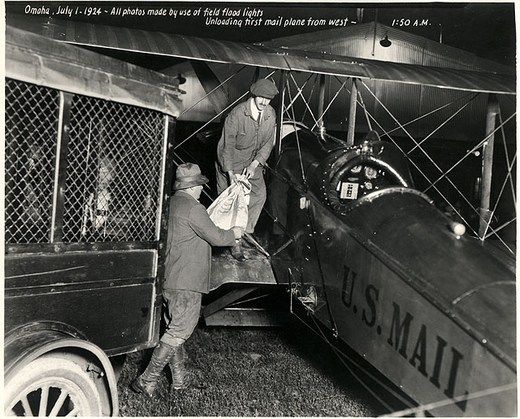

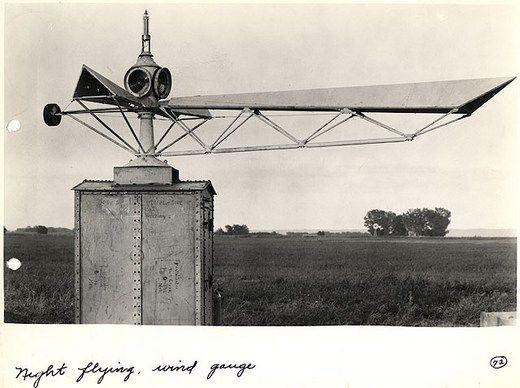

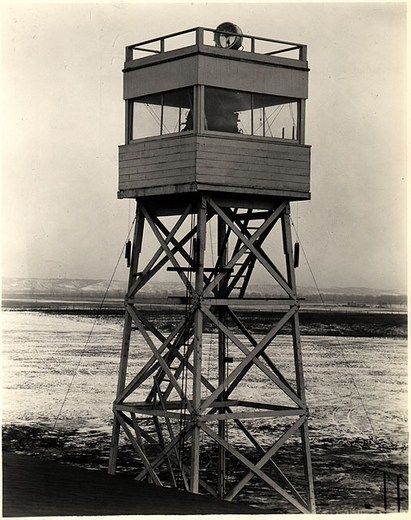

The de Havilland DH-4s used in the experiment were equipped with lights and other gear developed by the U.S. Army Air Service: landing, navigation, and cockpit lights; flares; and new starters and batteries. Once the tests were successful, the Post Office set up powerful, three-foot-diameter beacons at each major airfield, 18-inch beacons at emergency landing fields 25 miles apart, and 250 acetylene beacons at three-mile intervals along the route. With these lights in place, uninterrupted coast-to-coast air service began on July 1, 1924.

“We were like children venturing from home,” pilot Dean Smith wrote about the first night flights in his memoir By the Seat of my Pants. “It felt empty and lonesome out there, even with the beacons flashing, four or five visible ahead; we felt the fear of the unknown, the excitement of pioneering, and the satisfaction of the accomplishment.”

A greater accomplishment came in 1925 with the expansion of the night airway eastward from Chicago. Historian William Leary called the lighted route between Chicago and Cleveland “one of the wonders of early aviation.” But it would take more than beacons on the ground to expand the route from Cleveland to New York.

The de Havilland DH-4s that began service with the Post Office had unreliable compasses and airspeed indicators and an altimeter with measurements too coarse to be useful under 1,000 feet. Airmail pilots, out of necessity, were among the first to test advances in those instruments. A rudimentary barometric altimeter, for example, perfected by the Kollsman Instrument Company in 1928, was created by airmail technicians in Cleveland in 1925.

Paul Henderson, who was neither a pilot nor inventor and who had the unglamorous title of Second Assistant Postmaster General, deserves a good deal of the credit for developing the infrastructure that made night flying possible. In 1926, with the transcontinental route complete, the Post Office transferred the responsibility for infrastructure to the Department of Commerce. By 1933, 1,500 beacons created an 18,000-mile system of airways.