More than 70 Years Later, Rabaul’s Aerial Battleground Is Still Haunting

The “Japanese Gibraltar” was the scene of desperate fighting in the fall of 1943.

:focal(1175x513:1176x514)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/7f/b9/7fb99e79-42af-42ba-961c-0903a2e8940f/rabaul_simpson_harbor_pan_11-5-12.jpg)

I was well acquainted with Rabaul long before I went there. As a space shuttle astronaut in the 1990s, I had looked down from Earth orbit on the active volcanoes at this Papua New Guinea site on the island of New Britain. It wasn’t until last year, though, that I visited for myself to see traces of the World War II aerial battles for which Rabaul is best known—battles that culminated in a series of dramatic Allied raids 76 years ago this month.

Simpson Harbor, the drowned throat of a fuming volcanic caldera, is in fact best seen from the Rabaul volcanological observatory. The ridgetop site offers sweeping views of this superb anchorage, whose capture by Japan in January 1942 enabled the Imperial Japanese Navy to project sea and air power into the Solomon Islands, New Guinea, and the surrounding waters. Rabaul became a Japanese Gibraltar.

After the Americans seized Guadalcanal, 660 miles to the southeast, in August 1942, the Japanese mounted their counterstroke through Rabaul. Bristling warships of the infamous Tokyo Express steamed down “The Slot,” intent on retaking Guadalcanal, and Japanese airfields ringing the harbor launched strike after strike at the shoestring U.S. Marine air group on Henderson Field.

Even before Guadalcanal, American and allied aircraft struck back at Rabaul. Beginning in the spring of 1942, medium and heavy bombers, from B-26 Marauders to B-24 Liberators, made the long run over New Guinea’s Owen Stanley Mountains to hit the enemy base. Later, from Guadalcanal’s Henderson Field and from bases along the Solomon chain, more bombers rose to attack shipping, destroy supply dumps, and cripple Japanese air strength.

Rabaul was the most heavily defended target in the southwest Pacific, ringed by 367 anti-aircraft guns. Allied attempts to damage the base gave rise to savage sea, air, and land engagements from 1942 to 1945, claiming hundreds of planes and pilots.

Today, the Kokopo War Museum near the Vunakanau Japanese airfield preserves an eclectic collection of heavily weathered weaponry and aircraft. The museum’s tropical lawn is littered with large-caliber Japanese flak guns, salvaged aero engines, and the fuselage and wings of a Mitsubishi A6M2 Model 21 Zero fighter.

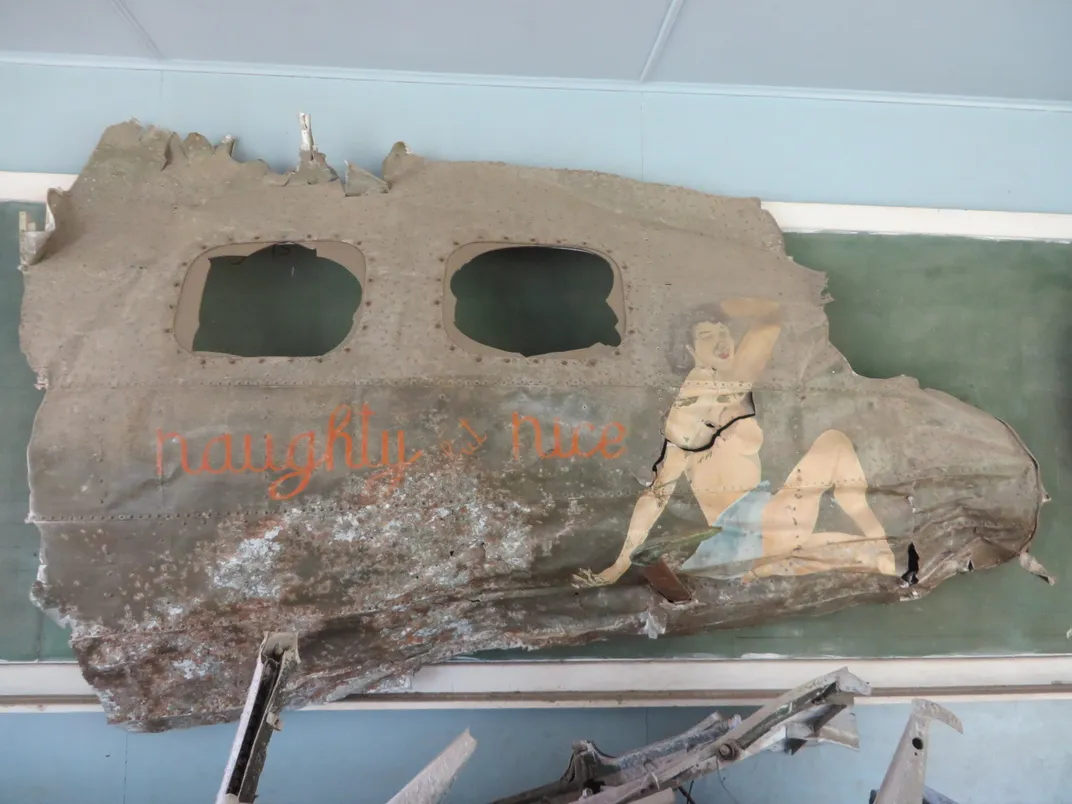

On the museum’s second floor are cockpit fragments of the B-17E Flying Fortress, Naughty But Nice. Early on the morning of June 26, 1943, darkness cloaked the bomber’s 10-man crew as they dodged searchlights and intense flak to unload their bombs on Vunakanau. First Lieutenant Jose Holguin, the navigator, had already set course for their home field on New Guinea when a Nakajima J1N1 Gekko night fighter raked the B-17 with a hail of 20mm cannon fire. Exploding shells killed the pilot and ignited the left wing. Only Holguin got out of the spiraling bomber, parachuting into the jungle below. Locals nursed his fractured spine and bullet wounds in his jaw and left leg, but eventually surrendered him to the Japanese in hopes of getting him medical help.

What Holguin received instead was two years of brutal interrogation, slow starvation, and medical neglect. At war’s end, he was one of only nine Allied prisoners liberated from Rabaul. He returned in the 1980s, determined to help locate his crewmates’ remains; the last were recovered from the impact site in 2001.

In the ash-draped, scattered buildings of old Rabaul town, the New Guinea Club, a pre-war gathering spot for Australian residents, now exhibits the salvaged drop tank from a Zero fighter, along with wing segments bearing Rising Sun insignia, canopy frames, and an arsenal of Japanese automatic weapons. The twisted, nearly abstract fuselage of a Nakajima Ki-43-I “Oscar” fighter, shot down in 1943, still bears its weathered green camouflage and red “meatball.”

Next door is the underground command center for the Japanese naval antiaircraft defenses. Built of reinforced concrete, the whitewashed interior still bears military graffiti and a plotting chart to track incoming Allied raids. Because of his visit in April 1943, days before his plane was shot down by U.S. Army Air Forces P-38 Lightning fighters, the command post is still called the Yamamoto Bunker.

Near the wartime Lakunai airstrip, a wrecked Mitsubishi Ki-21 “Sally” twin-engine bomber is the largest aircraft to be seen around Rabaul. Exhumed from under three feet of ash after a 1994 eruption, the forlorn Sally is stark evidence of the pounding delivered by the Allied aerial siege. By February 1944, the bombers had destroyed so many aircraft that the Japanese withdrew their few surviving planes to Truk. For the rest of the war, the 97,000-man garrison defending Rabaul went underground, waiting for an invasion that never came.

For the Allied aircrews running its gauntlet of flak and fighters, Rabaul was a living hell. It was even worse for those shot down and captured by the Japanese. The saddest Rabaul relics are the more than 300 miles of tunnels and bomb shelters dug into the volcanic rock by slave laborers and Allied POWs. In early 1944, the Japanese ordered captured airmen into a shallow cave, ostensibly to avoid incessant air raids. The site is still visible on Observatory Road. Enduring hellish heat, filth, and crowding, and given no food or water, the prisoners hung on by sucking dew from the tunnel’s blackout curtain. On March 4 and 5, 1944, Japanese guards, angered by a particularly heavy Allied raid, marched out 21 prisoners, who were likely executed in an atrocity known as the Tunnel Hill Massacre.

The handful of airmen who survived would never forget their ordeal. Today, those still visible relics of the Pacific air war in and around Rabaul are powerful reminders of the courage and dedication of those who flew, and fought, and fell.