Lighter Than Air

An illustrated history of balloons and airships.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/Lighter-than-Air-flash.jpg)

A senior aeronautics curator at the National Air and Space Museum, Tom Crouch has written extensively about the Wright brothers and other pioneers of flight. His newest book, Johns Hopkins University Press, 2009, $35), is a thoroughly researched and engagingly written history of buoyant flight from the balloonists of the 18th century to the military airship crews of World War II. The following excerpt is from a chapter titled “The Fabulous Silvery Fishes: The History of Rigid and Non-Rigid Airships, 1914–1945.”

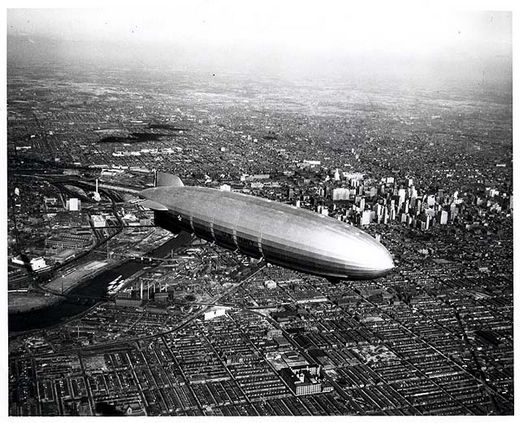

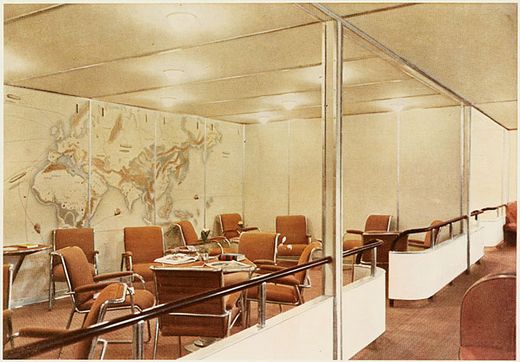

They were ships in the sky, and to watch one of the great craft pass majestically overhead was an emotional experience never to be forgotten. That was certainly the case for young John McCormick, an eight-year-old Iowa boy who stood with his grandmother as Graf Zeppelin flew directly over the family farm in the summer of 1929. The great dirigible was so low, he recalled six decades later, that they could see “every crease and contour from nose to fins…so low that we could see, or imagined we could see, people waving at us from the slanted windows of its passenger gondola.” Grandmother and grandson stood entranced. “Slowly, slowly the ship moved over us, beyond us, and at last was gone.”

Four-year-old David Lewis was on a Sunday outing in the family Dodge in 1935, when his mother suddenly exclaimed, “There’s a Zeppelin!” “Its engines,” he recalled, “hummed with a sound that reverberates in my memory seventy years later.” As an adult, Lewis wondered if that misty memory had been only a dream, until he saw a photo of the craft he had seen that day, and it all came flooding back. “The sound…echoing as the dirigible disappeared in the west, reaches out to me across the gulf of time that separates me from the child, yet connects me to a life-altering experience.”

So it was for Anne Chotzinoff Grossman, of Ridgefield, Connecticut, who encountered the Hindenburg in the fall of 1936. The shy first-grader was waiting for the bell that would end recess, when the shadow of the airship passed across the schoolyard. With her older brother Blair and his friends leading the way, she set off in pursuit. “We ran across fields and brooks and over stone walls, trying to keep the airship in sight.” Finally admitting defeat, “we made our way back to school, very late and very dirty, to face angry teachers.” She was ordered to the blackboard to write one hundred times, “I will not chase the Hindenburg”—a pretty tall order for a six-year-old.

Hugo Eckener, who guided the Zeppelin Company and its airships through the vagaries of politics and weather for four decades, understood the emotional experience evoked by the sight of a rigid airship cruising through the sky. “The mass of the mighty airship hull, which seemed matched by its lightness and grace,” he noted, “never failed to make a strong impression on people’s minds. It was…a fabulous silvery fish. Floating quietly in the ocean of air and captivating the eye…. And this fairy-like apparition, which seemed to melt into the silvery-blue background of the sky, when it appeared far away, lighted by the sun, seemed to be coming from another world and to be returned there like a dream.”

Copyright 2009 Johns Hopkins University Press