Glenn Curtiss Was Here

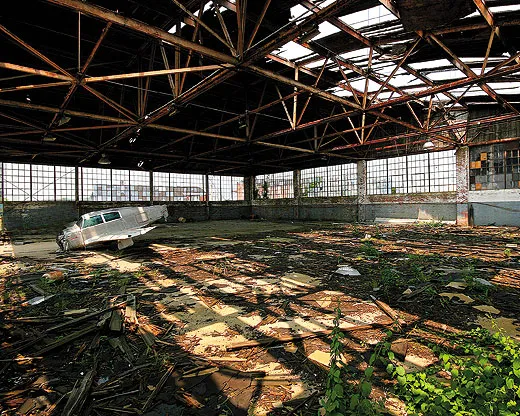

A 1920s hangar still stands at a Connecticut airport.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/Glenn-Curtiss-Was-Here-9-1-2012-3_FLASH.jpg)

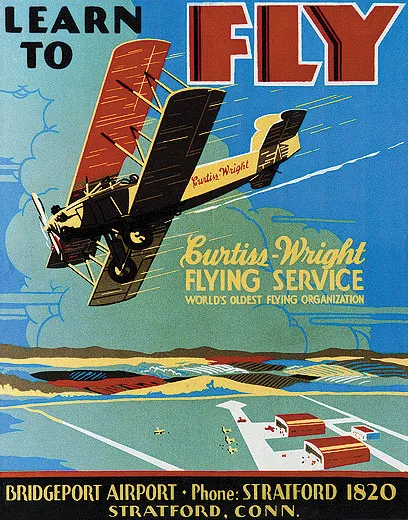

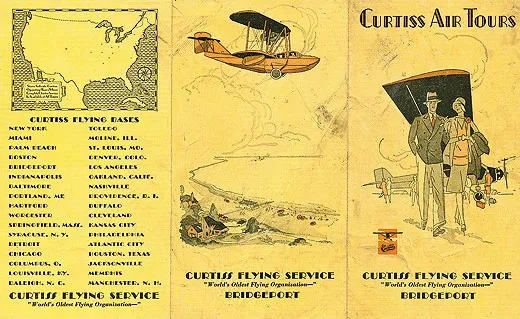

In 1928, Glenn Curtiss opened a branch of his flying school at a Stratford, Connecticut airport on Long Island Sound and painted his distinctive cursive logo on two new hangars, the first permanent structures at what is now Igor I. Sikorsky Memorial Airport, named for the Russian-American aviation pioneer. But the Great Depression forced the newly merged Curtiss-Wright to shrink operations, and the company withdrew from Stratford in the early 1930s.

In the decades since Curtiss called the airport home, other businesses have moved in and out, repainting the larger hangar with their logos and colors. As each company moved on, the paint faded and peeled, revealing the Curtiss name. Today, light filters through holes in the corrugated iron roof of the abandoned hangar and rubbish soaks in rainwater pooled on the concrete floor. Outside, an engine starts, then stutters, the sound echoing across the airport as a Cessna takes off.

The hangar is the focus of the Connecticut Air and Space Center, which wants to restore it as its headquarters and an aviation museum. The center’s executive director Andrew King expects to soon sign a long-term lease to relocate his group to the hangar, which will require renovations of up to $1 million.

In arranging King’s lease, the town of Stratford had to work with the neighboring city of Bridgeport, which bought the airfield in 1937. The two municipalities squabbled over the airport for decades, particularly regarding how much responsibility each bore for upgrades. But the current mayors say their common goal of supporting the Air and Space Center will help both cities, which were hit hard by the recession.

The Stratford grounds were first used as a racetrack in 1910, and soon airplanes began landing on the infield. It wasn’t until 1928, after Stratford officials signed a construction agreement with Bridgeport Airport, that the airfield was incorporated, with the Curtiss Flying School holding the lease. The following year, Igor Sikorsky built his flying boat factory next door, and Sikorsky and other aviation companies, including Chance-Vought, joined the holding company United Aircraft and Transport. In 1939, Vought and Sikorsky merged. That year, Sikorsky’s VS-300 lifted off near Vought-Sikorsky Building 6 to become the world’s first practical helicopter. Within a few years, Sikorsky was focused exclusively on helicopters, while Vought cranked out military aircraft like the F4U Corsair. For a while, the prototype XF4U was housed in a Curtiss hangar.

Morgan Kaolian remembers his first trip to the airport: It was 1936, and he was on a Sunday drive with his parents. They posed for a photo near the Curtiss hangar with a Vought Corsair biplane. Bridgeport Flying Services had by then taken over the lease from Curtiss. To fit its trainer aircraft in the hangar, BFS stacked them on their noses in custom-built blocks.

Kaolian took a joyride with his father in a Curtiss biplane. He still recalls sitting next to his dad as they circled over the saltwater marsh. He even remembers his pilot’s name: George “Zeke” Zahorsky, who, like several other Bridgeport Flying Service employees, became a Vought production test pilot.

In the early 1960s, Kaolian ran an ad agency in the original airport manager’s office and was responsible for repainting the hangar. Back then, he says, painters used chemicals in their oil-based paint to speed up drying. But the additives also reduced the longevity of the finish, which may be why the paint repeatedly peeled from the Curtiss logo. Kaolian became the airport manager in the 1970s, logging 34,000 hours teaching people to fly and making daily traffic reports.

The Air and Space Center expects to overhaul the Curtiss hangar within three years, and will also renovate the 1928 airport manager’s office. A structural engineer has already certified the soundness of the hangar’s steel frame. The Center has several Sikorsky helicopters, a Cessna O2A Skymaster and T-37 Tweet, a Lockheed T-33 Shooting Star, and a Northrop T-38 Talon. As a centerpiece of the restored hangar, the museum will showcase the FG-1D Goodyear-built F4U Corsair that had long sat atop a pylon at the airport entrance. Last year, Center volunteers took it to Breckenridge, Texas, where, with help from Ezell Aviation, they rebuilt much of the aircraft. In return, Ezell used it as a guide for restoring a Brewster-built F3A Corsair.

A native of England, Richard Mallory Allnutt is a photographer and aviation writer who has lived in the United States since childhood. To contribute to the Connecticut Air and Space Center, visit ctairandspace.org.