The Day Tammie Jo Shults Stepped Up

When disaster occurred at 32,000 feet, a veteran airline pilot knew exactly what to do.

:focal(1750x400:1751x401)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/81/09/810960d6-d1b8-49f1-864b-aa5e52c17ecd/tammie-jo-shults.jpg)

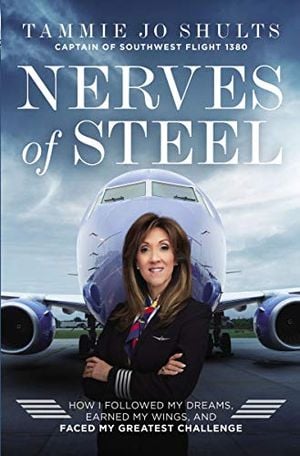

On April 17, 2018, Southwest Airlines Flight 1380 experienced an uncontained engine failure that crippled the Boeing 737, caused a cabin depressurization, and led to the death of a passenger among the 144 onboard. In the cockpit was First Officer Darren Ellisor and Captain Tammie Jo Shults, a former U.S. Navy fighter pilot. Shults wasn’t initially sure the aircraft would stay intact for a safe landing, and her autobiography, Nerves of Steel, is a riveting story that shows how her life experience served her well on that stressful day. Shults spoke with Air & Space senior associate editor Diane Tedeschi in October.

Why did you decide to write this book?

I have always read true stories and enjoyed gaining experience and wisdom through these “field trips.” When the spotlight from Southwest Airlines Flight 1380 shone on those of us involved, I decided I might have something to contribute.

Was the F/A-18 as much fun to fly as it looks?

More. Much more. If you think about the difference between watching a thrilling ride—a roller coaster, for example—and then actually riding one, you will have the beginning of an idea of how dynamically thrilling the F/A-18 is. Then add in not only riding but controlling it. Now you can start to imagine how demanding and amazing it is to fly the Hornet. Since it could boast a 1:1 thrust-to-drag ratio, you could point the nose straight up and defy gravity for about 30,000 feet. Or hum along the ground at a blurring speed and make shapes and colors meld into an impressionist’s perspective. My favorite flying was getting to use all of that in a single mission.

What was the first sign something was wrong aboard Flight 1380?

It was sudden and violent. We thought we had been hit by another aircraft. Darren and I instinctively grabbed the controls and leveled the wings. We fed in right rudder to pull the nose around and correct the skid, shallowing the dive that had naturally occurred when so much drag had been created at such a high altitude and with such a heavy aircraft. We could only “treat the symptoms” for a while, keeping control of the aircraft our priority. We would not know all the damage until we were on the ground. Descending through 10,000 feet, we had a call from the flight attendants to tell us about the window being [blown] out, the struggle to recover the passenger that had sat near the window, and the need for us to slow the aircraft down so they could assist her back into the cabin.

Did any of the skills you developed as a military pilot help you that day?

Yes. All of them. We only learn to fly once, and my background is Navy. My experience there emphasized hand-flying, airmanship, maintaining control of the aircraft, and “head work,” as the Navy calls it: common sense and keeping a healthy sense of priorities.

It has been reported that the Boeing 737 you were flying rolled 40 degrees to the left after the left engine came apart. How did you counter that left roll?

The aircraft did not roll to 40 degrees. It did a snap roll to the left, and Darren and I caught and stopped it passing 40 degrees.

What was the biggest challenge in landing the aircraft?

Remaining flexible and creative. We were about 10,000 pounds overweight for landing. And when we wanted to add power from the right [undamaged] engine, there was not enough rudder authority to compensate for the left skid. That meant the power we had anticipated using to level off over Philadelphia [the emergency landing site] and fly a stable pattern was not available. We were much more of a glider at that point, and we had to anticipate our glide path to the runway without using all of the remaining thrust.

The timing of extending the flaps and landing gear to arrive on the runway—not short of it—was our biggest challenge down close to the ground. I chose to use very little flaps. I could see some of the damage to our wing, and I could feel the drag versus power we had available. I chose flaps 5, which is a good tradeoff of lift for drag and allows a lower approach speed. If we landed too fast, we would blow our tires. There were also a few moments of having to figure out the last right-hand turn—into the thrust-producing engine. We began our approach to landing about 270 knots, slowing to about 160 knots before touching down on the runway.

Do you have any advice for young people who might be considering a career in aviation?

Aspirations mean nothing if you don’t act on them. Get started! “Adventure is worthwhile,” as Amelia Earhart once said. There are so many ways to begin—with no monetary expense. It will cost you time and effort. Go to captainshults.com and find links to places you can get free ground school and even scholarships to get started flying.

A Note to our Readers

Smithsonian magazine participates in affiliate link advertising programs. If you purchase an item through these links, we receive a commission.