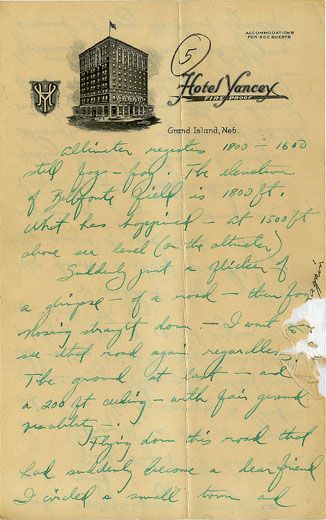

“Hell Stretch”

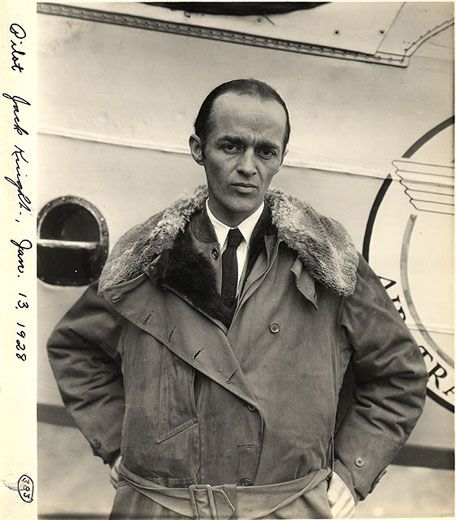

The man who saved the airmail describes the fearsome flight across the Alleghenies in 1919.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/f4/23/f4231795-d831-412b-8f08-4ccee2dc1ef5/jack_white_2.jpg)

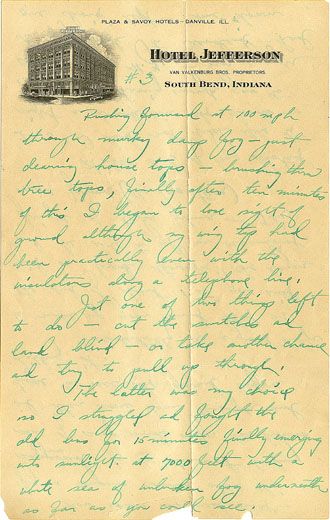

Jack Knight became famous in February 1921 for flying the first overnight trip to carry the mail from North Platte, Nebraska, to Chicago. But the more harrowing journeys he and his fellow airmail pilots faced were the flights over the Allegheny mountains between Cleveland and New York. The pilots developed a coffin humor about this leg of the trip, which they called “hell stretch.”

In Knight’s notes recalling the experience (see page images and transcription below), the pilot refers to the “variety of weather, ranging from dense fog, to sleet and freezing mist—interspersed with terrific blizzards.” In an open cockpit biplane, the trip must have been at best a miserable experience; frequently it was a fatal one.

The notes appear to have been written in hotels where Knight stayed when he flew the mail on the central part of the transcontinental route. After he became famous, he was probably urged by newspaper editors and others to tell his stories of flying the mail.

The notes are part of the James H. “Jack” Knight Collection donated to the National Air and Space Museum archives in 1988 by J. Ted Beebe.

Flying the U.S. Mail: Hold Everything—1919 Version

Introduction, Part 1

Our business of flying the U.S. Air Mail has changed considerably, since 1919.

In the old days—the motto was—The mail must go—regardless of fog, sleet, etc. We were flying Liberty motorized DHA ships, and in those days the Liberty Motor had many bad faults, such as burning out bearings—breaking connecting rods, stripping cam shafts, gears, etc.

It was truly a survival of the “fittest” (and luckiest) because any of the pilots in 1919 would pull out of a terminal field in fog and practically impossible weather rather than risk the possibility of another ship flying in while they were held up for weather.

The Allegheny Mountains between Cleveland and New York have a choice variety of weather, ranging from dense fog, to sleet and freezing mist—interspersed with terrific blizzards.

The character of the terrain is such that at times our future health [and] happiness depended on our [“motto”?] “in good weather”—Well! In bad weather we hung on every explosion of the exhaust with a prayer. (A thankful prayer.)

Deep gullies and high hills heavily timbered made fog flying a very risky touchy affair. Flying at 30 to 50 feet with never over 100 feet forward visibility in the average fog—made a great many angels of good pilots. Rushing thru this murk at 100 M.P.H.—Suddenly a wooded hillside looms up—just about 1/10 of a second of indecision and it’s just too bad.

Scene 1, Part 2

Woodland Hills Park—improvised flying field 1919 for U.S. Air Mail.

Superintendant—field manager chief mechanic and pilot in office waiting for mail truck to find its way from Cleveland P.O. to air field.

Very dense fog limiting ground visibility to about 200 feet. Pilot apparently very nervous—divides his time smoking cigarettes and looking out of window trying to kid himself into believing that the fog is lifting and flying conditions are getting better.

Superintendant very irritable and apparently determined that if mail truck gets to field—pilot will fly it out—or else.

Well! The [truck] arrived—it was my turn to go—the other ship had left New York—where flying conditions were better. Weather at Bellefonte (our intermediate station) was reported “dense fog” with probability of clearing. Bellefonte 215 miles distant, and in the heart of the Allegheny Mountains approximately 2’-10” [2 hours, 10 minutes] flying if things went well.

Climbing into my suit as slowly as possible—without invoking suspicion that I was stalling for a few more additional minutes.

“Pull the blocks,”—another minute gained in adjusting goggles and final inspection of motor instruments—finally a half hearted wave to chief mechanic—and I fed her the gun and was off in the fog.

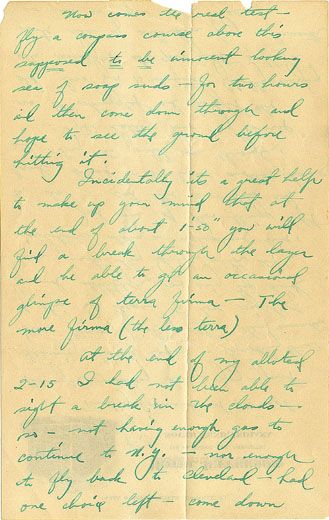

Pushing forward at 100 mph through murky damp fog—just clearing house tops—brushing thru tree tops, finally after ten minutes of this I began to lose sight of ground although my wing tip had been practically even with the insulators along a telephone line.

Just one of two things left to do—cut the switches and land blind—or take another chance and try to pull up through.

The latter was my choice so I struggled and fought the old [“bus”?] for 15 minutes finally emerging into sunlight at 7000 feet with a white sea of unbroken fog underneath as far as [I could] see.

Now cam[e the] real test—fly a compass course above this supposed to be innocent looking sea of soap suds—for two hours and then come down through and hope to see the ground before hitting it.

Incidentally it’s a great help to make up your mind that at the end of about 1’-50” you will find a break through the layer and be able to get an occasional glimpse of terra firma—the more firma (the less terra).

At the end of my allotted 2-15 I had not been able to sight a break in the clouds—so—not having enough gas to continue to N.Y.—nor enough to fly back to Cleveland—had one choice left—come down through and pray fervently that the angel of good luck remain roosted on your shoulder until you have landed & stopped rolling.

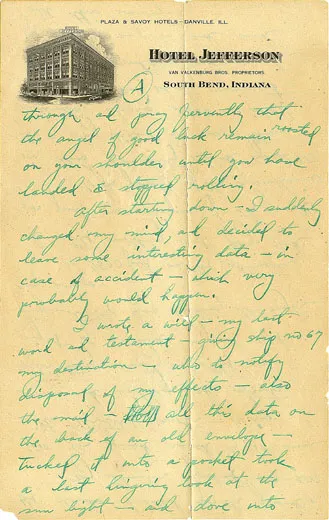

After starting down—I suddenly changed my mind, and decided to leave some interesting data—in case of accident—which very probably would happen.

I wrote a will—my last word and testament—giving ship no. 67 my destination—who to notify disposal of my effects—also the mail—all this data on the back of an old envelope—tucked it into a pocket took a last lingering look at the sun light—and dove into the clouds headed for the ground.

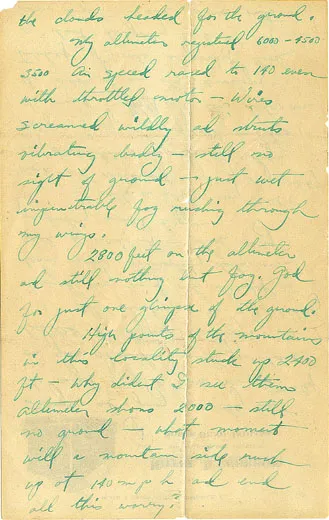

My altimeter registered 6000-4500 3500 air speed raised to 140 even with throttled motor—wires screamed wildly and struts vibrating badly—still no sight of ground—just wet impenetrable fog rushing through my wings.

2800 feet on the altimeter and still nothing but fog. God for just one glimpse of the ground.

High points of the mountains in this locality stuck up 2400 ft—why didn’t I see them altimeter shows 2000—still no ground—what moment will a mountain side rush up at 140 mph and end all this worry?

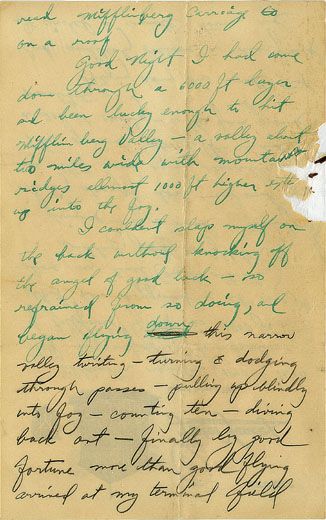

Altimeter registers 1800-1600 still fog—fog. The elevation of Bellefonte field is 1800 ft. What has happened—at 1500 ft above sea level (on the altimeter).

Suddenly just a flicker of a glimpse—of a road—then fog again. Nosing straight down—I want to see that road again regardless. The ground at last—and a 200 ft ceiling—with fair ground visibility.

Flying down this road that had suddenly become a dear friend I circled a small town and read Mifflinberg Carriage Co on a roof.

Good night I had some [?] through a 6000 ft layer and been lucky enough to hit Mifflinberg Valley—a valley about two miles wide with mountainous ridges almost 1000 ft higher extending up into the fog.

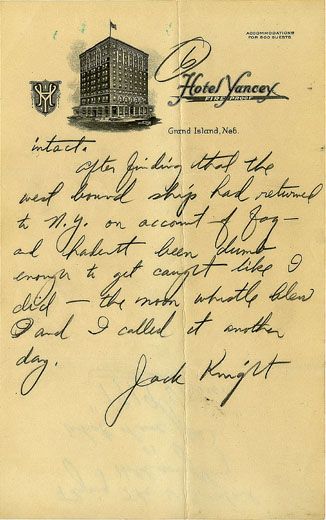

I couldn’t slap myself on the back without knocking off the angel of good luck—so refrained from so doing, and began flying down this narrow valley twisting—turning & dodging through passes—pulling up blindly into fog—counting ten—diving back out—finally by good fortune more than good flying arrived at my terminal field intact.

After finding that the west bound ship had returned to N.Y. on account of fog—and hadn’t been dumb enough to get caught like I did—the noon whistle blew and I called it another day.

--Jack Knight