A Century Before Elon Musk, There Was Fritz von Opel

With the Austrian visionary Max Valier, this German tycoon started the world’s first rocket program.

:focal(2237x1118:2238x1119)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/34/05/3405e971-1139-43e8-97a9-2757f5274a4a/fritz-von-opel-im-rak-2-502775.jpg)

This may sound familiar: One of the world’s richest men—also a charismatic figure skilled at public relations—starts his own privately funded automobile and rocket business, with a goal to revolutionize both fields.

If Fritz von Opel seems like a clone of Elon Musk, there are differences. He worked in the 1920s, not the 2020s. Von Opel inherited his fortune rather than making it himself. Although he has a significant place in the history of rocketry, he was more financier than engineer. And finally, while Musk might actually succeed in transforming space travel, for von Opel it was more of a side interest.

Fritz von Opel, who died 50 years ago this month, was born in 1899. He was the son of Wilhelm von Opel, whose automobile manufacturing business led him to became known as “the Henry Ford of Germany.” After graduating from the Technical University of Darmstadt with a degree in engineering, Fritz was made director of testing for the Opel car works and put in charge of publicity. The latter suited his flamboyant personality, as he was already well known in Germany as a sportsman and winner of speedboat, motorbike, and automobile races.

Like other car manufacturers at the time, the Opel company had a hand in early aviation. In 1909 it put up a $4,000 prize, most likely for a distance record, and by 1912 was producing a 60-hp aircraft engine. But Fritz von Opel’s introduction to rockets came in 1927, when he became acquainted with the Austrian science popularizer Max Valier, then the leading European champion of the possibility of spaceflight.

Valier’s life had been changed three years earlier by reading Hermann Oberth’s The Rocket into Interplanetary Space, the first detailed plan for how humankind might achieve spaceflight with the development of liquid-propellant rockets fueled either by liquid oxygen and alcohol or liquid oxygen and liquid hydrogen. Taken as he was with Oberth’s ideas, Valier thought the book was “unintelligible” to the layperson, since it was loaded with advanced mathematics. But he understood the astounding significance of what Oberth was proposing: The liquid-propellant rocket was the true key to venturing out into the solar system and beyond.

After reading Oberth’s book in January 1924, Valier proposed to the author and to the publisher Oldenbourg that he would popularize the book by means of illustrated articles and lantern-slide lectures, and could even collaborate with Oberth on another book geared to the lay reader. Valier ended up writing it on his own. His Der Vorstoss in den Weltraum (The Advance into Space) came out in 1925, and was a phenomenal success. Raketenfahrt: Eine Technische Möglichkeit (Rocket Travel: A Technical Possibility), followed three years later, and also was hugely popular. In addition, he wrote a stream of magazine and newspaper articles on space travel and lectured widely on the topic. Valier thus became one of the premier explainers of Oberth’s ideas for spaceflight, and even advanced some futuristic visions of his own.

While Oberth was primarily a theorist, Valier wanted to see his ideas put into action. So, as early as mid-July 1924, Valier had already conceived a way to help build an experimental liquid-propellant rocket, although it wasn’t until 1927 that he started to create what was, in effect, his own space program.

He needed a backer, though. After striking out with the Junkers aircraft company and several foreign companies, he turned in the autumn of 1927 to Fritz von Opel. The young car tycoon saw the possibilities at once, especially the publicity he could gain for himself and his family's company. On December 8, a contract was signed between Valier and von Opel, which included in its final phase a partnership in a venture toward human rocket flights.

Also signing on to the contract was Friedrich Sander, who owned a pyrotechnical company in Wesermünde, on Germany’s North Sea coast. There he produced gunpowder-fueled rockets with life-saving ropes for offshore rescue operations, as well as signal rockets for merchant and other ships. Sander’s rockets, in their steel casings, were quite reliable for the day, even if they produced an extremely smoky exhaust.

In early 1928 Valier and Sander ran a series of elementary static tests at Wesermünde to record the basics of rocket thrust production and burn times. Meanwhile, at Opel’s sprawling automobile plant in Rüsselsheim am Main, between Frankfurt and Mainz, Fritz monitored the construction of a special car to be fitted with banks of Sander rockets. He and Valier had agreed that a rocket car, using a standard Opel chassis, would be the first step in Valier's development of rockets for space travel.

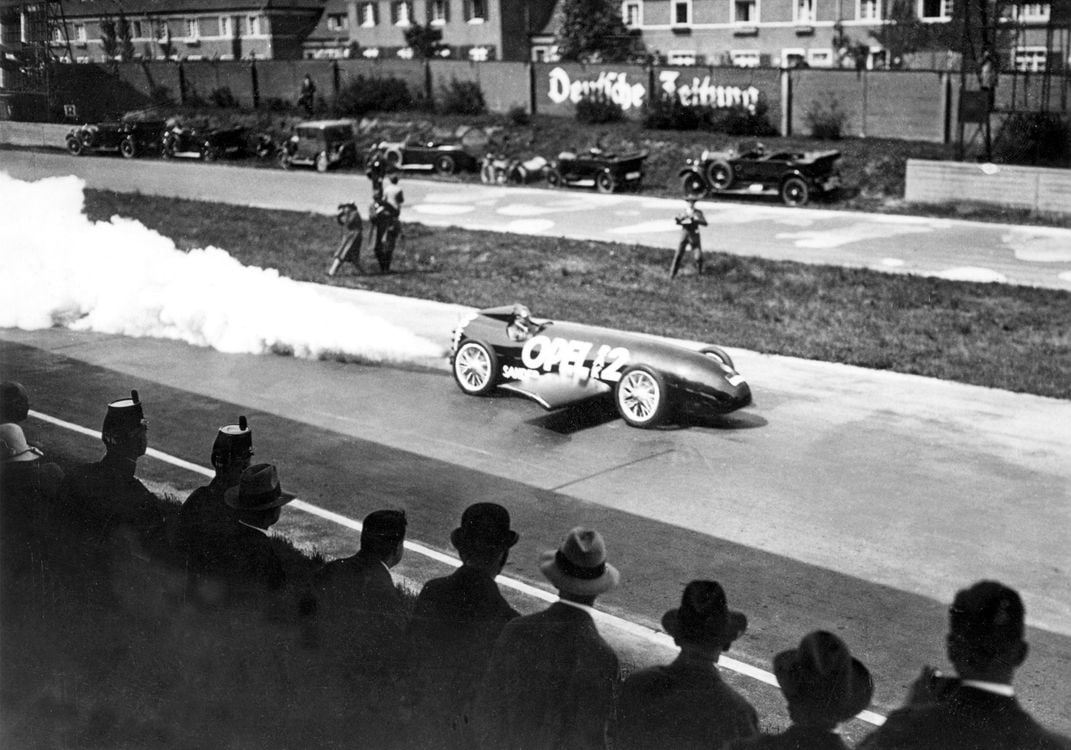

On March 12, on a track located at the Opel plant, former race car driver Kurt C. Volkhart took his seat at the controls of the shiny black car to get ready for its first trial run. Boldly emblazoned on both sides of the car was the name “Opel,” attesting to the fact that this was more of a publicity stunt than an engineering breakthrough. In fact, because it used ordinary solid-propellant rockets, Opel’s vehicle didn’t really advance rocket technology at all.

The Opel-RAK 1, as it was called, reached 47 mph on its first test, and graduated to higher-thrust Sander rockets. On May 23, Von Opel himself took the wheel for the first public demonstration at Berlin’s Avus Speedway, before crowds and newsreel cameramen. This Opel-RAK 2 car, with a full bank of 24 higher-thrust Sander rockets, attained a top speed of 143 mph.

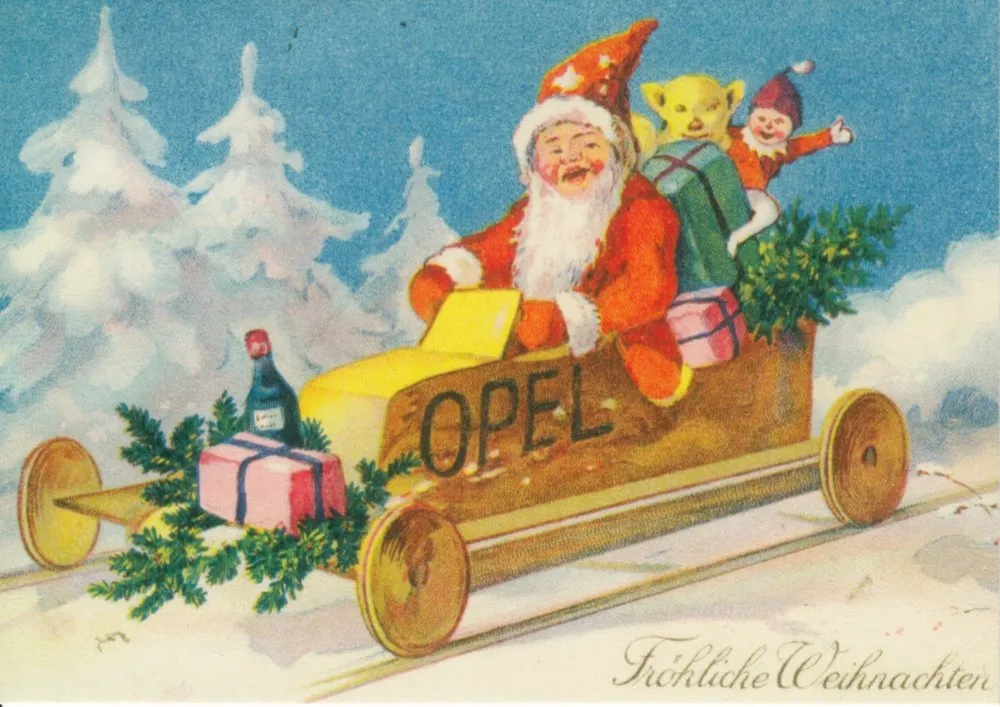

If nothing else, these stunts brought rocket propulsion to the attention of the general public and led to a minor fad—called Raketenrumnmel, or “rocket rumble.” Even 16-year old Wernher von Braun was bitten by the bug, constructing his own homemade rocket car and nearly killing himself in the process. The Opel RAK cars appeared in everything from advertisements to poems, Christmas cards, and commemorative coins. In a way, they previewed the surge of space-oriented toys and popular culture leading up to the Space Age of the late 1950s.

Opel’s rocket cars soon led to other stunts: the “RAK 3” railway car experiments of 1928, rocket-powered motorcycles (nicknamed “The Monster”), boats, ice sleds, and inevitably, rocket-powered airplanes. In fact, Valier and von Opel had started work on a rocket plane back in mid-March, just three days before the first Opel-RAK 1 trial. Valier and Sander had gone to a popular gliding spot in the Rhön mountains to speak with the famous airplane designer Alexander Lippisch and Fritz Stamer, a prominent glider pilot, about the feasibility of installing Sander’s rockets on one of the planes.

As a result of this meeting, von Opel purchased a small, tailless canard-type aircraft built by Lippisch and attached a series of Sander’s rockets in a box-like arrangement. On June 11, Stamer flew this aircraft, named the Ente (“Duck”), for a few meters under rocket power. Although a number of experimental model rocket planes had been flown in the 1880s, and perhaps even earlier, this was likely the first full-scale rocket plane flight with a pilot onboard.

A second version followed, designed and built by Julius Hatry, and von Opel himself briefly flew this plane for a few seconds (it was actually more of a hop) at Frankfurt-am-Main on September 30, 1929. Von Opel proclaimed it the “world’s first rocket plane,” conveniently ignoring that it had been preceded by Stamer’s and Hatry’s earlier attempts.

By that time, the partnership between Valier, von Opel and Sander had already come apart. In his book, Raketenfahrt, Valier blamed their falling out on “scientific and personal differences.” Valier continued to pursue his spaceflight plans, this time collaborating with industrialist Paul Heylandt, whose specialty was manufacturing containers and transporters for super-cold liquified gases like liquid oxygen. Heylandt was completely enthralled by Valier’s visionary concepts for spaceflight using liquid-fueled rockets. With his backing, Valier got as far as building a rocket engine that ran for 22 minutes on March 22, 1930. With that confidence booster, he announced that he was working on a rocket plane to fly across the English Channel in record time, which would be an important step leading to spaceflight. Sadly, he never got a chance to see it through. During a static rocket test on May 17, he was killed when a rocket motor exploded and a piece of shrapnel pierced his aorta.

As for von Opel, not long after Vallier cut ties with him he left the family business when the company was bought out by General Motors. A millionaire at the age of 30, he and his wife moved to the United States by 1940. After the war he returned to Europe, spending most of his time yachting around the Cote d’Azur.

Von Opel died of diabetes at San Moritz in April 1971, and so lived long enough to see the early Apollo flights to the moon. Neither he nor Max Valier probably envisioned how far rocketry would progress in a single lifetime.