The Black Christmas Disaster

Zero visibility and four aircraft inbound: It quickly became the worst single day in early commercial aviation.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/f0/7c/f07c2a35-aa4b-4d45-8787-2a695e76681a/04g_am2018_lunghwadc20013arrive1935_live.jpg)

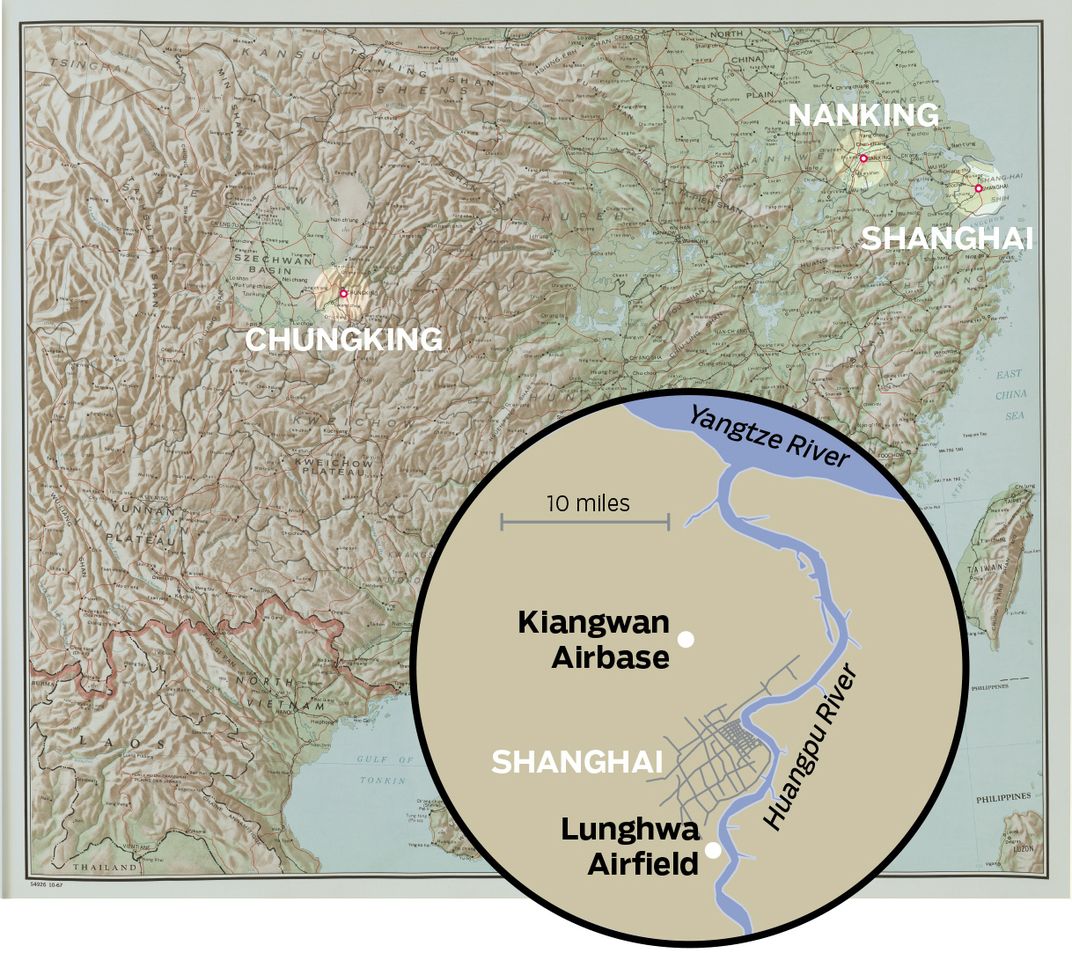

A heavy fog blanketed the airport in Shanghai, where four airliners were bound. A city on China’s eastern shore, where the Yangtze and Huangpu rivers run into the East China Sea, Shanghai has a climate not unlike San Francisco’s, with a morning fog that usually burns off by lunchtime. But on Christmas day 1946, instead of dissipating, the fog grew thicker as the day wore on. At the city’s Lunghwa Airport, tensions rose as visibility reached zero. Nervous airport staff who had been out celebrating the holiday began to report in once they heard about the incoming flights, whose pilots circled for hours, burning up fuel reserves and trying to get a glimpse of the runways below.

World War II had just ended. While most other countries were rebuilding from the devastation, China was still embroiled in its own civil war. It was an already vicious struggle that was escalating in 1946, and both sides—the Nationalists under Chiang Kai-shek and the Communists under Mao Tse-tung—were spending heavily to support their causes. As a result there was little money in China to repair war damage, and even less to improve infrastructure.

Lunghwa Airport, a hub for China’s struggling airlines, China National Aviation Corporation (CNAC) and Central Air Transport Corporation (CATC), was woefully inadequate for the traffic. With runways made from grass and gravel, the airport could be hard to spot even on clear days. In fog, the single light at the end of each runway became virtually invisible, leaving a radio beacon as the only indicator to a pilot that the aircraft was approaching its destination.

About 15 miles north of Lunghwa, Kiangwan Airfield was still being operated by the U.S. military. The air controllers had adapted a revolutionary new technology developed by the British and installed during the war at Kiangwan. The ground control approach (GCA) system comprised two oscillating radar antennas set up next to the runway; one scanned the airspace up and down and the other side to side, to about 30 miles out. In poor weather, a tower operator could locate inbound aircraft on a radarscope that displayed two paths: One showed how far to the left or right the aircraft was from the inbound path; the other showed how far above or below path it was. With these visual cues, the controller could direct the pilot to change his heading or altitude and talk him down until he could see the runway. The incoming aircraft needed only a functioning two-way radio and a pilot with basic instrument flying skills. The system was still so new that it wouldn’t be installed for testing at U.S. airports for another four months. (It finally went into general service at Washington National Airport outside the District of Columbia in 1952.)

William McDonald was CNAC’s chief pilot; he had come to the company after years in China with Claire Chennault and the Flying Tigers. McDonald was concerned about his airline’s safety procedures; in the past three years there had been at least 32 CNAC crashes in the region, killing over 100 people. He insisted, among other things, that company pilots get training on the GCA system in order to use Kiangwan in an emergency. But his reports show that Kiangwan’s control tower suffered from a faulty power supply and during the fall of 1946, the radar system wasn’t operational at least a quarter of the time. Of the 42 CNAC pilots who applied to practice on the system, only a few were able to complete a GCA landing by the end of the year.

**********

Early on December 25, McDonald was informed of the degrading weather conditions. After consulting with the station in Kiangwan, he ordered Lunghwa to close, sending home everyone except one officer, a clerk, and a Morse code operator. Pan American executive Lincoln Reynolds arrived at the airport around 6 a.m., hoping to get the first flight out to Nanking, and found it already closed. He was in Shanghai to work with Chinese officials in modernizing and expanding CNAC service (CNAC was a Pan Am subsidiary). After waiting several hours, he returned to town. He probably felt some relief at the delay. In 1933, Reynolds had suffered a broken neck in an airplane crash after his CNAC flight out of Shanghai took off despite heavy fog.

On December 25, CNAC senior tower operator Ronald Kliene, scheduled for a midnight shift, was called in to report to Lunghwa early; he later wrote an account of that day, with the observations of the staff who witnessed the events. His report and many others from the Christmas disaster have been collected by CNAC historian Tom Moore, whose uncle was a pilot for the company before he was killed in a 1942 crash. Moore has devoted years to gathering correspondence and remembrances about CNAC personnel that he publishes at cnac.org.

Kliene writes in his report that the morning started out calm. “The office of Flight Operations at Lunghwa Airport had had very little to do all day. It had been raining persistently with low cloud and fog dominating the whole eastern seaboard.” Many flight and ground personnel were celebrating the holiday in Shanghai. “The large influx of American servicemen to the city over the past year guaranteed a surfeit of parties and dances at military bases and clubs,” writes Kliene. Among the partiers was CNAC pilot Peter Goutiere, who wrote about the day in his memoir. “By the time I arrived back at the house, the weather was zero-zero, no visibility at all. It now sounded as if there were several planes milling around upstairs.” The tower controller had been monitoring radio transmissions, and by late afternoon the staff knew that four flights were still en route to Shanghai, all originating from Chungking, about 1,000 miles to the west: CNAC flights 115, 140, and 147 and CATC Flight 48.

At the controls of Flight 140, Captain James Greenwood was expecting his wife and children to arrive from the States to spend Christmas with him. Greenwood was relatively new to CNAC, but he was an accomplished pilot with years of commercial airline experience. Originally from Houston, Texas, he had come out to China because the salaries were better there. He was flying a DC-3 with 27 passengers and two other crew members. Flight 140 was scheduled to make several stops, including one at Nanking. Greenwood had made several attempts to land there, but was thwarted by fog. Visibility around Nanking deteriorated rapidly to zero, and the airport was ordered closed with Greenwood circling above.

Captain Rolf B. Preus was piloting Flight 115, a C-46 Curtiss Commando carrying 31 passengers and a crew of three. Preus, 30, was also an experienced pilot, having spent almost a year flying the route over the Himalayas known as the Hump, considered the most hazardous flight path in the world. Growing more and more concerned about fog, Preus radioed Greenwood over Nanking. They decided that their best chance was to fly on to Shanghai.

The captain of Flight 147, Francis Joseph Michiels, was born in Belgium but learned to fly in the U.S. Civilian Training Program during World War II. He later became an instructor, training U.S. and British military pilots in California, before joining CNAC in September 1945. His C-46 carried 17 passengers and three crew.

Tommy Wing was captain of the lone CATC flight, 48, a C-47 with seven passengers and three other crew members. Wing was a U.S. citizen, born in Chicago, and was previously a CNAC pilot. He was known for his sense of humor, and was well liked by his colleagues. Unfortunately for him, CNAC had two payroll schedules: The one for Chinese pilots was considerably lower than the one for Americans, and Wing’s employers placed him on the Chinese scale. For additional income, he had taken to smuggling cigarettes, but he was found out and fired. He simply walked over to the CATC offices, an airline that paid the same wages to all aircrew, and was hired.

Flight 48 was the first to reach Shanghai, and Wing was given permission to land at the military base if he could. Once there, he was instructed to attempt a GCA approach, although he had never used the system. “The first warning of the enormity of what was to follow was a call from Kiangwan airbase,” writes Kliene. “A CATC flight had made several attempts to land there…but all attempts had failed despite the best efforts of their radar assisted landing procedures.” CNAC pilot Oliver Glenn, who had avoided flying on Christmas day because he was recovering from pneumonia, later recounted what he’d heard from another pilot who was on the ground in Lunghwa that night: “[Wing] had probably never heard of a GCA and certainly had never practiced one. He shot the approach but must have been a little high and was told to ‘Take a wave-off—Take a wave-off!’ ”

Around 5:45 p.m., Wing’s aircraft banked to the left on descent. The C-47 struck the roof of a nearby building and cartwheeled into a neighborhood, killing several people on the ground. All 11 souls on Flight 48 were lost.

Pan Am’s Lincoln Reynolds was nearby at a pilot’s house getting ready for Christmas dinner when the phone rang at 6:45 p.m. with word of the crash. “The next great shock was the news that three CNAC planes were overhead trying to get in,” Reynolds wrote in a letter to his wife a week later. “I immediately went outside to look at the weather. It was not possible to see across the compound, 100 feet or so away.” He and the pilot rushed back to the airport.

Despite the failure of Flight 48, McDonald believed the GCA was the best hope at getting everyone safely on the ground. Still, he anguished over the decision. McDonald had been working to improve landing conditions throughout China. “I requested Col. Hsia to install night landing lights at Tsingtao [an airport north of Shanghai] but his reply was so ludicrous that I started taking action myself,” he wrote later. “On the night of December 25, Tsingtao weather was extremely good,” but the airport crew had never finished installing the lights.

Flights 140 and 147 had now arrived in Shanghai. McDonald had no other options, so he ordered Greenwood and Michiels to Kiangwan. Greenwood arrived first, but he found he couldn’t establish contact with the tower due to an intermittent radio failure in his DC-3. Unable to use the GCA system, he turned back to Lunghwa, leaving Michiels circling Kiangwan at 4,000 feet.

At Lunghwa, McDonald ordered the ground crew to pour strips of gasoline along the runways and light them, to make up for the dim beacon now failing to penetrate the fog. McDonald talked to Greenwood as best he could through the faulty radio, calmly guiding the pilot in. “In the tower his engines could be clearly heard but his flashing navigation lights were invisible, nor had anyone seen his forward landing lights,” writes Kliene.

Trying to spot Flight 140, Reynolds had climbed up to the hangar roof, and as he listened to the aircraft make low passes over runway, he began reliving his own crash. “All was deathly silent on the field. The only sound was that of the plane in the distance, getting louder and louder as it approached the field from the southwest…. I was shaking so hard I could hardly conceal it from those around me.” Then over the radio Greenwood’s calm voice announced that he had lost an engine. “McDonald stepped out onto the outer balcony of the tower in case the aircraft could be seen,” Kliene writes. “The spluttering of an engine was heard, then an eerie silence for a few seconds. The impact exploded from the wet darkness with mind shattering force.” A second aircraft had gone down.

Rescue personnel, including CNAC’s chief doctor, Charles F. Hoey, rushed to the crash site. Kliene reported that “Greenwood had aligned his aircraft correctly but, out of fuel, had stalled.” The aircraft came down in the intersection of two runways, skidding 1,000 yards and somersaulting at the end of the tarmac into the airfield. When the rescue team arrived, it was too late to save most of the victims, but Hoey and his staff waded through heavy rain and mud to reach several passengers. Reports on the number of fatalities differ, but the most realistic indicate that of the 30 people on board, 10 survived. Captain Greenwood did not make it. His recently arrived wife and children would return to the United States with his body.

“It was now abundantly clear that the other approaching aircraft was in extreme danger,” writes Kliene. “The crew would have heard the last transmissions of CNAC 140.” Preus, aboard Flight 115, was the only one of the four pilots who had experience with the GCA system, but the radio in his C-46 couldn’t transmit on the high frequency required to use it. Now perilously low on fuel, Preus called into Lunghwa that he was on a “long final.”

The people in the tower had been able to see his forward landing beams for just a moment, about 50 feet off the runway. Preus called in that he wasn’t happy with his first approach and would go around. Reynolds had gone back in the tower to wait. “[Preus] flew back and forth over the field several times, coming down as low as he dared. The Lunghwa Pagoda and chimneys of a nearby cement plant were serious hazards in the soup that hid them…. [McDonald] was talking to him all the time. He was calm and confident…. The fog had seemed to lighten a little. When it seemed he was nearing the inner marker there was a sudden, dull-like sound and then again that awful silence.”

It took rescue workers hours to find the wreckage. The airplane had crashed short of the airport in an area criss-crossed by canals, so naval craft were used to reach it. The C-46 had hit the ground, then skidded into a schoolhouse—fortunately empty—and started a small fire. The wreckage was massive, and the personnel who reached the scene declared that all 31 passengers had died. Preus survived, but with disfiguring injuries that caused enormous pain the rest of his life. He was sent back to the United States for treatment, and had his left leg amputated a few months later. Seven years later he developed leukemia, and died in 1959. He told friends later about the crash: “When I was trying to land in the fog, I only had time to pray ‘Dear God, please take care of me, Thy will be done,’ then I had to concentrate on my instruments again.”

In the Lunghwa tower, the catastrophic events of the preceding minutes had left everyone stunned, writes Kliene. “The numbing silence in the tower was broken by the sound of Captain Michiels’ voice: ‘Lunghwa Tower, this is See-nac 147. Landed Kiangwan 19:04. Over and out.’ ”

Francis Joseph Michiels was a big man, well thought of by all, but after Christmas 1946 he was judged a real hero. When he reached Kiangwan that night, his radio was able to pick up the ground instructions as he nosed his C-46 toward the runway. He knew about the GCA system but had never used it. Pilot Oliver Glenn wrote later that the secret of GCA is the pilot’s faith in the system; Michiels, truly flying blind, had surely mustered all his faith to follow the instructions that came through his headphones as the operators, watching Flight 147 on their radar, began talking him down. Michiels later told a colleague that he didn’t know if he saw the runway lights first or touched down first. “He was a damn cool customer to be able to do that,” writes Glenn of his friend. “Besides, he was the funniest guy I ever knew.” Later, after Michiels had been diagnosed with cancer, he used humor to deal with his illness. “When he was being treated for cancer he said he got so much radiation that his neighbors’ garage doors opened when he drove down the street,” remembers Glenn. Michiels died in 1982.

While the four flights known to be en route to Shanghai were now accounted for, there was one more flight that remained a mystery. Carrying 10 passengers, it had filed a plan for Shanghai but had never reported in, and for almost 24 hours it was feared lost. Finally airport staff learned that it had turned around and returned safely to Chungking.

The final count of those who died on Black Christmas, as it came to be called by CNAC pilots, is difficult to calculate. Records are incomplete, eyewitnesses disagreed, and the aftermath was so horrible that confusion overtook record keeping. Several reports have the body count as 62, yet one official report has it as high as 71, and Kliene’s account says 74 were killed on impact or died later of their injuries. Three of those killed were occupants of the houses near Kiangwan. Among the Flight 115 passengers who died was an air traffic control student on board for training. Two final victims of the Christmas tragedy were medics injured at Lunghwa after their ambulance ran off the road in the fog.

The effect on Shanghai’s air future was immediate. Within months, the airlines, driven by the horror of the crashes and by Chinese officials threatening to charge airline executives with criminal negligence, added a new runway at Lunghwa, along with high-intensity lights capable of penetrating fog.

In the wake of all the devastation, there was one heartening discovery. On December 26, the United Press sent out a single-line update from Shanghai: “When salvage crews lifted the wreckage of one of the planes they found 4-year-old Wong Didi fast asleep—the only uninjured survivor of the aerial accidents.”