Aboriginal Astronomers Saw Stellar Blowup in 1843

The idea that ancient cultures were keen observers of the night sky is neither surprising nor new: think of the Druids, the Mayans, and the Babylonians. But most examples from the annals of archaeoastronomy seem to come from the northern hemisphere.Now a team of researchers from Macquarie Universit…

The idea that ancient cultures were keen observers of the night sky is neither surprising nor new: think of the Druids, the Mayans, and the Babylonians. But most examples from the annals of archaeoastronomy seem to come from the northern hemisphere.

Now a team of researchers from Macquarie University in Austrlia is reporting what they believe is the only indigenous record of one of the most spectacular southern astronomical events of the 19th century.

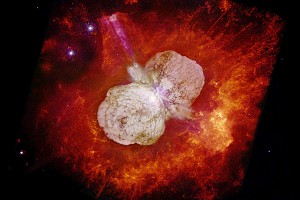

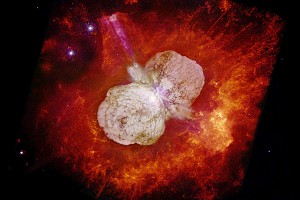

This Hubble image of the binary star Eta Carinae has always been one of my favorites. It looks like an explosion—which is exactly what it is. In 1843, this "hypergiant" star system, 100 times more massive than our sun and four million times as luminous, suddenly flared up to become brighter than every star in the sky except Sirius. Astronomers still aren't sure exactly what prompts Eta Carinae's periodic outbursts—it isn't a supernova, although it may someday become one. And by 1858 the star had settled back to its normal brightness, just as it always does.

A few years after the 1843 "Great Eruption," William Stanbridge, a wealthy Australian landowner, went out among the Boorong people of northwest Victoria to collect information on their knowledge of and myths about the night sky. Stanbridge found "two members of a Boorong family who had the reputation of having the best astronomical knowledge in the community," according to the Macquarie researchers. They sat down at "a small campfire under the stars, located on a large plain near Lake Tyrell," and talked about the sky overhead.

One of the stars named by the Boorong was Collowgullouric War, meaning "female crow," which the researchers identify (in a paper to be published in the Journal for Astronomical History and Heritage), as Eta Carinae. The dramatic temporary brightening "would have been widely observed by most, if not all, indigenous peoples of the southern hemisphere," say the authors. But as far as they can tell, Stanbridge's 1858 report is the only mention of it in the literature. Read the full paper here.

Now a team of researchers from Macquarie University in Austrlia is reporting what they believe is the only indigenous record of one of the most spectacular southern astronomical events of the 19th century.

This Hubble image of the binary star Eta Carinae has always been one of my favorites. It looks like an explosion—which is exactly what it is. In 1843, this "hypergiant" star system, 100 times more massive than our sun and four million times as luminous, suddenly flared up to become brighter than every star in the sky except Sirius. Astronomers still aren't sure exactly what prompts Eta Carinae's periodic outbursts—it isn't a supernova, although it may someday become one. And by 1858 the star had settled back to its normal brightness, just as it always does.

A few years after the 1843 "Great Eruption," William Stanbridge, a wealthy Australian landowner, went out among the Boorong people of northwest Victoria to collect information on their knowledge of and myths about the night sky. Stanbridge found "two members of a Boorong family who had the reputation of having the best astronomical knowledge in the community," according to the Macquarie researchers. They sat down at "a small campfire under the stars, located on a large plain near Lake Tyrell," and talked about the sky overhead.

One of the stars named by the Boorong was Collowgullouric War, meaning "female crow," which the researchers identify (in a paper to be published in the Journal for Astronomical History and Heritage), as Eta Carinae. The dramatic temporary brightening "would have been widely observed by most, if not all, indigenous peoples of the southern hemisphere," say the authors. But as far as they can tell, Stanbridge's 1858 report is the only mention of it in the literature. Read the full paper here.