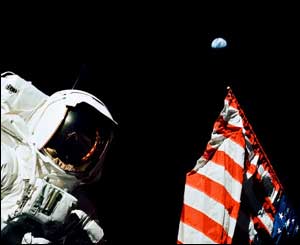

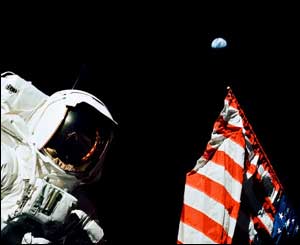

A Moonwalker Views His Old Stomping Grounds

Having settled into a new, lower orbit just 31 miles above the lunar surface, the Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter recently passed over the Apollo 17 site.We emailed moonwalker Harrison Schmitt, the Apollo 17 lunar module pilot and the only geologist—the only scientist—to have walked on the moon, and a…

Having settled into a new, lower orbit just 31 miles above the lunar surface, the Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter recently passed over the Apollo 17 site.

We emailed moonwalker Harrison Schmitt, the Apollo 17 lunar module pilot and the only geologist—the only scientist—to have walked on the moon, and asked him if he'd seen the new photos of his old stomping grounds. He had. Anything strike him as different from the way it looked in December 1972?

"The most surprising geological aspect of the image is the very dark area that begins about 100 meters north of the SEP site," he replied. "This is probably a concentration of black pyroclastic beads (also seen at Shorty Crater) in the regolith. If we had been able to see it before the Apollo 17 mission, we probably would have picked a station there for a stop on the way to Station 6 (the large boulder site at the base of the North Massif)."

When asked if there's anything he'd like to see in more detail on future LRO passes, Schmitt had a ready answer. "I suspect that they plan eventually to image the entire area; but a comparable image of Shorty Crater where we found the orange pyroclasitc glass and of the boulder tracks on the walls of the valley would be of great interest. This resolution and sun angle may make it possible to map the distribution of pyroclastic glass throughout the area and region."

What else did he think was noteworthy? "The very dark rectangle a the LRV final parking spot is puzzling," he said. "Something drastically changed the albedo of the upper surface of the LRV, probably the result of changes to the materials of the seats or because of deposits from broken silver-zinc batteries. Similary, the area immediately arouund the Challenger descent stage appears darkened, also probably because of contamination from the materials or fluids in the stage.

"Our EVA 1-3 LRV tracks away from the landing area are not obvious," he continued, "but I suspect other versions of the image will show them. That will be more difficult because the landing area had been lightened by the winnowing of fine material from the top of the regolith giving a very thin albedo enhancement. Tracks in this area look dark because of stirring up the normal dark regolith from below this enhancement.

"Just seeing this overhead, high sun angle detail of the Apollo 17 landing site in the Valley of Taurus-Littrow strikes my interest!" Schmitt wrote. "The pre-Apollo 17 photography we had for planning was at lower sun angles and at least ten times lower resolution. Having a record of our activities in the vicinity of the Challenger stirs great memories. My appreciation and awe goes to Mark Robinson and his LRO team."

We emailed moonwalker Harrison Schmitt, the Apollo 17 lunar module pilot and the only geologist—the only scientist—to have walked on the moon, and asked him if he'd seen the new photos of his old stomping grounds. He had. Anything strike him as different from the way it looked in December 1972?

"The most surprising geological aspect of the image is the very dark area that begins about 100 meters north of the SEP site," he replied. "This is probably a concentration of black pyroclastic beads (also seen at Shorty Crater) in the regolith. If we had been able to see it before the Apollo 17 mission, we probably would have picked a station there for a stop on the way to Station 6 (the large boulder site at the base of the North Massif)."

When asked if there's anything he'd like to see in more detail on future LRO passes, Schmitt had a ready answer. "I suspect that they plan eventually to image the entire area; but a comparable image of Shorty Crater where we found the orange pyroclasitc glass and of the boulder tracks on the walls of the valley would be of great interest. This resolution and sun angle may make it possible to map the distribution of pyroclastic glass throughout the area and region."

What else did he think was noteworthy? "The very dark rectangle a the LRV final parking spot is puzzling," he said. "Something drastically changed the albedo of the upper surface of the LRV, probably the result of changes to the materials of the seats or because of deposits from broken silver-zinc batteries. Similary, the area immediately arouund the Challenger descent stage appears darkened, also probably because of contamination from the materials or fluids in the stage.

"Our EVA 1-3 LRV tracks away from the landing area are not obvious," he continued, "but I suspect other versions of the image will show them. That will be more difficult because the landing area had been lightened by the winnowing of fine material from the top of the regolith giving a very thin albedo enhancement. Tracks in this area look dark because of stirring up the normal dark regolith from below this enhancement.

"Just seeing this overhead, high sun angle detail of the Apollo 17 landing site in the Valley of Taurus-Littrow strikes my interest!" Schmitt wrote. "The pre-Apollo 17 photography we had for planning was at lower sun angles and at least ten times lower resolution. Having a record of our activities in the vicinity of the Challenger stirs great memories. My appreciation and awe goes to Mark Robinson and his LRO team."