Scorned at First, These Seven Airplanes (Finally) Proved Their Mettle

Did they defy skeptics, or just outlast them?

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/61/d3/61d30ee7-18a5-4f10-ad9b-a6552da1940f/06m_on2060_b1b_5921053_live.jpg)

First impressions can be misleading. The history of aviation is filled with stories about aircraft that seemed to have limited value but that over time exceeded expectations. We found seven notable aircraft that struggled through their early years to eventually prove their worth.

Mach-busting Bomber

There’s an old joke in Washington, D.C.: “What’s the difference between Dracula and the B-1 bomber?” Answer: “You can actually kill Dracula.”

To be sure, the B-1 experienced many near-death experiences during its long road to deployment, but survive it did. In the 1960s, Secretary of Defense Robert McNamara shelved the idea of a bomber to deliver nuclear weapons to Soviet targets, favoring ICBMs instead. The Nixon administration revived it, the Carter administration canceled it, and the Reagan administration brought it back—only to see the B-1 remain on the ground because of fuel leaks and engine failures. Worse, its brand-new radar-jamming system tended to wreak havoc on its own radar, prompting the Armed Forces Journal to award the bomber the humiliating title of “World’s First Self-Jamming Bomber.”

Even more demeaning for B-1 pilots, they were benched in 1991 during Operation Desert Storm. They weren’t equipped to carry conventional bombs, leaving the task to an aging fleet of B-52s. Redemption finally came in 1998, during Operation Desert Fox, when two B-1s destroyed the barracks of Iraq’s elite Republican Guards. It has been flying continually ever since, in Kosovo, Afghanistan, and most recently against ISIS. Pilots who fly the B-1, or “Bone” as they call it, say it flies more like a fighter than a bomber, thanks to a 40-degrees-per-second roll rate, afterburners for instant power, and 3-G combat maneuvering. “During a ride in the left seat of the B-1 flight simulator, I got a feel for the Bone’s agility,” wrote David Noland for Air & Space in 2008. “A firm yank on the stick triggered a roll rate that left me dizzy.”

That maneuverability, coupled with exceptional payload capacity, has endowed the B-1 with a tactical role never envisioned by its designers: keeping close to the combat zone while coordinating aerial strikes with ground troops. “Our favorite asset at the company level was the B-1,” Lou Frketic, an Army company commander in Afghanistan, told the Washington Post. “They had more ordnance and longer loiter times, and they delivered ordnance to the desired location without trying to second-guess us with their own optics.”

The Air Force, which plans to fly the B-1 until 2036, is contemplating new missions for the bomber, including arming it with hypersonic weapons.

Double the Fire Power

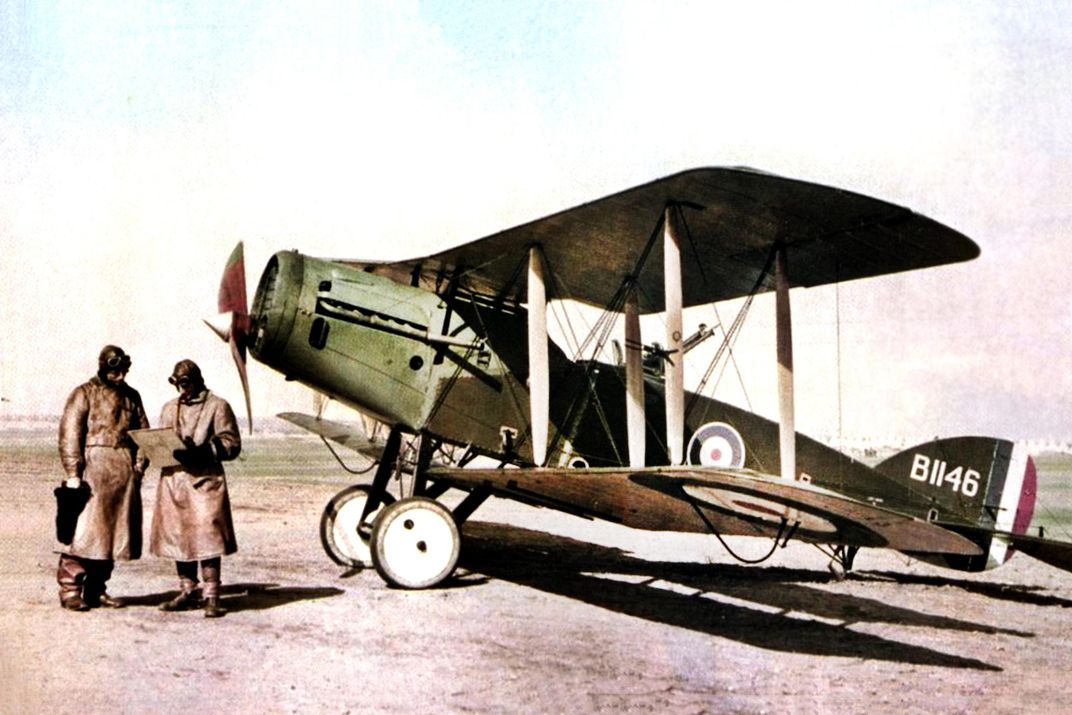

The Bristol F.2 was initially a disastrous solution to a disastrous problem. In 1915, just one year into the First World War, newly developed German aircraft were inflicting a terrible toll on British fliers. It became clear that the Royal Aircraft Factory BE2c—a cumbersome two-seat reconnaissance aircraft and light bomber—was outclassed and needed to be replaced. The press had dubbed it “Fokker Fodder.”

The two-seat Bristol F.2, known in the Royal Flying Corps as the “Brisfit,” offered several improvements over its predecessor. Whereas the gunner aboard a BE2c sat in front of the pilot—and had to return fire over the pilot’s head—the Brisfit was armed with both a synchronized, fixed, forward-firing Vickers machine gun for the pilot and a Lewis gun mounted on the observer’s rear cockpit. Only 52 of the initial model, the F.2A, were built before being supplanted by the F.2B—most of which were equipped with a powerful Rolls-Royce Falcon III liquid-cooled V12 engine, allowing the aircraft to climb at 889 feet per minute.

Yet the F.2’s initial foray into combat on April 5, 1917, was a catastrophe. An RFC patrol of six F.2As encountered a German squadron of five Albatros D.III biplanes. During the skirmish that followed, four F.2As were shot down and a fifth was badly damaged. Baron Manfred von Richthofen gloated that “the new British aeroplane was not to be feared.”

The RFC, however, came to realize that the fault lay not entirely in the airplane’s design but in the tactics. The pilots had been instructed to fly in the same tight defensive formation as the BE2c, relying on the crossfire of their rear gunners to fend off enemy aircraft. This made them easy prey for the Germans. But with the improved engines of the Brisfit, its pilots were able to revise their tactics and make the most of their airplanes’ speed and maneuverability. They began to fly their aircraft like single-seat dogfighters, with forward guns and an extra sting in the tail. “The back-to-back seating of pilot and rear gunner…made possible instant change from offense to defense and back again,” observed Royal Flying Corps Captain William Harvey while writing a history of his squadron after the war.

The Brisfit remained in service well after the First World War. It was finally retired in 1932.

Last of a Kind

Had it entered the Second World War sooner, the Curtiss SB2C Helldiver might have received a warmer welcome. But the dive-bomber’s introduction into service had been hampered by multiple delays. A prototype crashed two months after its maiden flight, a later version suffered structural failure of a wing during a diving test—killing the pilot—and, at one point during its development, the U.S. Navy demanded more than 880 modifications. Worse, the Helldiver had the misfortune of replacing the immensely popular Douglas SBD Dauntless—a light, maneuverable aircraft that had disabled three Japanese carriers at the Battle of Midway in less than eight minutes.

While the SBD had been dubbed “slow but deadly,” the SB2C became known among mechanics as “Son of a Bitch 2nd Class.”

And yet during the two years following its combat debut on November 11, 1943, the Helldiver sank more Japanese targets in the Pacific than any other U.S. or Allied aircraft. The Helldiver was faster than the Dauntless and could deliver its bombs with more precision. Ultimately, about 30 Navy squadrons operated Helldivers aboard 13 carriers.

Still, the aircraft was continually plagued by problems due, in part, to poor factory workmanship. The electrical system was unreliable, and the hydraulic system required frequent maintenance. The Helldiver underwent several upgrades, culminating in the SB2C-5, which featured a modified cockpit that grouped all electrically controlled equipment in a console on the pilot’s right side and all mechanical controls on the left. Instruments were located in panels in front of the pilot.

The Helldiver’s days were numbered, however. The development of air-to-surface rockets rendered dive-bombing obsolete. The SB2C remained in service until 1947, but it would be the last dive-bomber operated by the Navy.

Electronic War

Northrop Grumman’s EA-6B Prowler wasn’t the prettiest aircraft in the Navy and Marine Corps fleets (its nicknames included “Sky Pig”), but when it finally retired in 2019, it had served for nearly a half-century.

The secret to its longevity? It kept proving its worth, adapting to new missions even as it got older. It entered service in the skies over Vietnam—the first true electronic battlefield—jamming enemy radar and communications and conducting electronic surveillance. Decades later, in Iraq and Afghanistan, the Prowler was pivotal in disrupting ISIS communications and the radio signals used to set off improvised explosive devices.

Prior to the Prowler, engineers had tried putting electronic equipment into the bomb bays of B-25s, but the bombers weren’t fast enough to escort jets. So Grumman modified its own A-6 Intruders, giving the aircraft more powerful Pratt & Whitney J52 engines and sturdier landing gear.

Lieutenant Commander Ken O’Donnell, who flew an A-6 Intruder during Operation Desert Storm, was glad to have the Prowlers along. During that conflict, 12 Marine Corps Prowlers flew 516 flight hours, rendering U.S. bombers invisible to Iraqi detection and destroying ground radar. “We were able to have full dominance of the air,” O’Donnell told the Everett News. “No one was able to touch us.”

On March 14, 2019, the Marine Corps’ last Prowler made its final flight. During its 48 years of service, not a single one was lost in combat.

Most Recognizable Airliner

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/8c/dd/8cdd5baa-3315-4250-8150-3e69f18c03ca/06r_on2020_74715e_jj14_live.jpg)

The Boeing 747, the “Queen of the Skies” for nearly four decades, was expected to have a short reign as a passenger jet. “It was designed as an interim airliner, to carry lots of passengers until the Boeing 2707 SST would enter service,” says Bob van der Linden, the Curator of Air Transportation and Special Purpose Aircraft at the Smithsonian’s National Air and Space Museum. “They thought that they could sell about 400. Boeing has sold well over 1,500 and has changed the world in so doing. Not bad for an interim design.”

Indeed, when the 747 first took flight in 1969, both Boeing and Pan American had anticipated that it would soldier on as a cargo transport after its “inevitable” decline as a jumbo jet ferrying as many as 660 people per flight. The 747’s most distinctive feature, the teardrop-shaped hump above the main deck, was a design choice born of planned obsolescence as a passenger jet: Its purpose was to give the aircraft a hinged nose for a front-loading cargo door.

Yet that hump would be one of the features to usher in the age of glamorous air travel that the 747 came to symbolize. The extra space behind the cockpit became a piano bar and lounge, helping transform the travel experience into aviation’s equivalent of the cruise ship—glitzy, stately, yet affordable for almost everybody. And with its then-record-breaking speed of Mach 0.92 and range of 5,300 nautical miles, airlines in the Pacific, like Singapore and Cathay, seized on the opportunity to create new routes.

Although the 1973 oil crisis and airline deregulation brought an end to the piano bars, the 747 remained the largest airliner available for decades. The last one to carry passengers for a U.S. airline landed in Arizona on January 3, 2018.

Spycraft

Its initial four-year mission over the Soviet bloc would stretch into 60 years of global duty, as the U-2 (which re-entered Air Force service in 1957) proved its value time and again—alerting the United States to Soviet nuclear missiles entering Cuba; tracking weapons development in Iraq; surveilling battlefields in Korea, Vietnam, and Afghanistan.

Despite the introduction of the long-endurance, remotely piloted Global Hawk, the U-2 still flies—mainly because of its adaptability. “The U-2’s almost like Mr. Potato Head,” Major Travis “Lefty” Patterson, a U-2 pilot, said during an event at the Intrepid Sea, Air & Space Museum in New York City last May. “So you can take a pod off here and a nose off here and put a new thing on pretty quickly. Just because it’s got big wings, it’s got a big engine, so we’ve got a lot of size, weight, and power advantage over a lot of other high-altitude aircraft.”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/66/36/663674a1-c5bc-48e5-becd-7c7dc3ebc5b1/06q_on2060_u2traininggeneric960601-f-6300r-041_live.jpg)

One of America’s most iconic and enduring aircraft—and the first one ever built explicitly for espionage—began as a design submission that nobody asked for and that the Air Force wanted nothing to do with.

In 1953, the U.S. government—desperate for eyes in the sky above the Soviet Union and Eastern Europe—solicited three contractors for a reconnaissance aircraft that could fly on missions that stretched 6,400 miles at an altitude of 70,000 feet, beyond the reach of fighters and radar. When Lockheed heard about the project, it sent in its own proposal. The CL-282, designed by aviation legend Kelly Johnson, boasted long sailplane-style wings and, to reduce weight, it had only one engine and was stripped of armor and an ejection seat. The Air Force made its feelings known when General Curtis LeMay left during the CL-282 presentation, saying that the “whole business was a waste of time.”

But under pressure from President Dwight Eisenhower, the CIA took over the program and helped create the aircraft that would be designated U-2 ( “U” for “utility”), with the much livelier nickname “Dragon Lady.”

Swing-Wing Terrain Hugger

Ignoring the objections of a military selection board, Secretary of Defense Robert McNamara awarded an aircraft contract to General Dynamics that promised to fulfill his personal desire to save millions of dollars by using a common airframe for both the Air Force and the Navy. The Air Force got the F-111 to satisfy its requirements for a long-range, ground-hugging penetrator. For the Navy, the F-111B was supposed to be a carrier-based interceptor for fleet protection that would be able to engage Soviet bombers. But Navy pilots wanted an agile fighter, not a missile-armed behemoth. In 1968, the F-111B program was scuttled.

Initially, the Air Force F-111As didn’t fare much better. Three of the six aircraft deployed to Vietnam in 1968 crashed during the initial 55 missions. The losses were attributed to defective control actuators for the horizontal stabilizer, forcing the Air Force to spend $100 million correcting the malfunction. But Air Force officers defended the airplane, pointing out that its record of 21 accidents in its first 80,000 hours compared favorably with 39 for the Dassault Mirage and 33 for the Convair F‐106 Delta Dart.

Indeed, the F-111 and its variants went on to serve for 30 years. They flew more than 4,000 missions in Vietnam with only six combat losses. In 1986, the Air Force assigned 18 F-111Fs to Operation El Dorado Canyon, which struck high-profile targets inside Libya. During Operation Desert Storm, F-111s destroyed more than 1,500 Iraqi tanks and armored vehicles. When the F-111 was retired in 1996, its nickname was made official: The Aardvark, with its nose pointed down, hunting close to the ground.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/mark-strauss-240.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/mark-strauss-240.jpg)