The Enduring Mystique of the Venetian Lagoon

Among islands barely emerging from the water, you find yourself in an ageless world

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/af/4c/af4c3fe5-8e39-4bc7-b01d-c59ddc2489e1/istock_000071982101_large_1024.jpg)

The tamarisk trees are blooming along the canals of Torcello. Their dusty-white plumes, hazy in the still air, blur even more in the water’s reflections. At the Torcello stop, you’re let off the vaporetto and there’s nothing, just a path along a canal. Most people come to see the two ancient churches. They pause for a drink or lunch, then catch the boat again. By late afternoon, the island falls into a somnolent peace. I’ll stay for two nights in this old light and summer torpor, this odd spot where a Somerset Maugham or Graham Greene character might wash up. I was here 20 years ago. Little has changed. The path was sandy, now it’s bricked. Wild purple allium spikes the weedy fields. A few souvenir concessions and places to stop for a bite have arrived. Otherwise, the island is caught in time—a time before a place such as Venice could be imagined.

On the voyage out, I took a photo. I caught a flat expanse of glittering water, a milky sky with high wispy clouds, and between water and sky, the low horizon line of a distant island, so thin it looked like a green brushstroke dividing the two expanses. This watery realm—so different from Venice, where winding canals are alive with working boats and everywhere the waters shimmer with lights, colorful palace facades, striped mooring poles and black silhouettes of gondolas. But way out in the lagoon: silence, a soft palette of tawny grasses, sand and water turning from pewter to teal to the old green of a celadon cup. Among islands barely emerging from the water, you find yourself back at the beginning. The city of Venice once was like these, just an idea of land. How crazy to think of building where the water table percolates just under the surface of the ground.

Torcello goes way back. The bishop of Altino, not far away on the mainland, moved his followers here in a.d. 638. Altino, which traces back to the eighth to sixth centuries b.c.—and is now on my must-visit list—had been flattened by Attila in 452, and subsequently harassed by other invaders. Some say the low and marshy island called to the bishop in a vision. There, his people would be less vulnerable to attacks. In the shallow waters, channels had to be cut, and in times of danger the defenders pulled up the bricole, deep-water markers, leaving enemies to flounder in mud. After eight centuries of a thriving civilization on Torcello, malaria and silt ruined life on the island. People migrated onto the equally undependable strands that gradually became Venice. Torcello, you might say, is the mother of Venice. Thereafter, the island’s five towns, many churches and palaces were raided for building materials, reducing the place to the few structures remaining today. Now Torcello claims only ten residents.

I must have been in a thousand churches during my years in Italy. It’s something to sort through on nights of insomnia, but Torcello’s church of Santa Maria Assunta may be the most interesting one I’ve ever seen. Built in 639, rebuilt in 1008, altered again and again, it’s barny and beamed, squared off and interrupted by rood screens. High windows, shafts of gray light, traces of fresco, shutters made of stone slabs—it’s a crude relic with a powerful force. You might not be prepared for the stunning mosaics. At the west end, a depiction of the Harrowing of Hell, the seven deadly sins, and the Last Judgment in gory detail. Serpents weave in and out of the skulls of the envious near a section of dismembered parts belonging to the slothful; the gluttons eat their own hands. The messages are complex. Beware! A small child is actually the Antichrist in disguise. Who imagined that Adam and Eve were down in hell? The mosaics form a graphic narrative as scary now as it was to the 11th- and 12th-century worshippers. The east-wall mosaic is startlingly different. In a glittering, tessellated and very tall apse rises the simple elongated Madonna holding her Baby. If you have binoculars, you see that she is weeping. Her right hand gestures toward the infant, as if to say, “This way.” In her left hand she holds a small white cloth, which early viewers would have recognized as a foreshadowing of the shroud. There’s often a collapsing of time in images of the Madonna; this one is dazzling. Jan Morris, in her seminal book Venice, quotes a child of her acquaintance who described the mosaic as “a thin young lady, holding God.”

Actually, the whole complex collapses time. What moves me most is the spolia, all the surviving bits across the centuries incorporated into the still living building: exposed sections of mosaic from the original 639 floor, the seventh-century altar, some 11th-century marble panels, a Roman sarcophagus said to have held the remains of St. Eliodoro, fragments of 13th-century frescoes, the ninth-century holy water font. This has been sacred ground as far back as memory goes.

Santa Fosca, the adjacent brick church, is all architecture, a compact Greek cross base topped by a round structure that looks like a big iced cupcake with a flattened peak. Stripped inside, except for Byzantine marble columns, the space is still mesmerizing because you can’t help but connect to the mind of the architect and the square, round and octagonal solutions he found. Nearby, two small museums display mosaics, stone carvings, paintings and archaeological finds. Cunningly cast bronze probes, tweezers, keys, spoons open to us intimate glimpses of life on Torcello. From many islands in the lagoon you can see the campanile, the exclamation point of Torcello. It was even taller before 1696, when it was lowered after lightning lopped off the top. Too bad it’s closed today. I would like to have seen the brick-ramped interior, which must make it easier to climb up for the view.

Ernest Hemingway secluded himself on Torcello to write Across the River and Into the Trees. I too checked into Locanda Cipriani, occupying the room next to his. You can sit under a pergola, sipping a Negroni, and plot the next year of your life. You can read by the window with the scent of roses and jasmine wafting through the curtains, or meander along paths lined with pomegranates and hydrangeas. The inn is, by now, a large part of the recent history of the island. There’s Kim Novak on the wall, chomping down on a big bite of pasta. All the British royals come and go in faded black-and-white photographs. How young and slender Princess Diana was. There’s Elton John! And Steve Jobs was here too, though no photo records his visit. I would like to have stayed a week. The waiters loved to chat, the food was fresh from the sea, and the deep quiet made my tense shoulders relax within two hours.

My favorite waiter had not been to Venice—only a half-hour trip—in five years. When I heard that, my perspective suddenly shifted. To those who live on the less traveled islands, it’s their world. I left Torcello ready to explore as much as possible of the 210-square-mile lagoon, only 8 percent of which is land. I hopped on and off the vaporetti for a few days. They are working craft—the metro and bus routes of the lagoon. Once off the busy Venice, Burano and Murano routes, residents of the scattered islands are taking trips to the market, to the cemetery, to visit relatives, to school. Their days are on water, and their dreams must be of water.

I stepped off at Sant’Erasmo for a bucolic walk along fields where the coveted castraure artichokes are grown. Castrated because the prized first buds are cut off, encouraging fuller growth for the plant. Those early, two or three violet-tinged little prizes are tender enough to grate, sprinkle with olive oil and eat raw. The second wave is almost as delectable, and the third growth is the normal carciofo but still special for the large heart and the particular taste that comes from saline dirt. Others who disembarked there jumped onto their waiting bicycles and sped off to the scattered farms that grow much of Venice’s produce. There’s a small hotel on the island with bikes for rent. Next time!

A stop close to Venice, San Michele with its dark cypresses is the cemetery island. Extensive, well-tended mausoleums resembling immense marble chests of drawers give way at the wilder edge of the island to the Protestant plot, where many stones are broken, graves are in the ground and the cypresses look especially moribund. This area seems cautionary for expats like me. Here are those who died far from home—the final stops of Great-Aunt Emily on the grand tour, seamen who caught fevers and mysterious others such as one Archibald Campbell, died 1891, whose lonesome marker says: “The heart knoweth its own bitterness and the stranger intermeddleth not therewith.” This is a story we never will know. Ezra Pound lies neglected and weedy, in contrast to the only tended grave in the section, that of Russian poet Joseph Brodsky, all covered in blooms. Walking out, I can’t help but feel the contrast of the exiles’ abandoned stones with the elaborate private chapels of Italian families festooned with live flowers. Not lingering on such thoughts, I board the vaporetto again for the island San Lazzaro degli Armeni, where another wandering expat found solace.

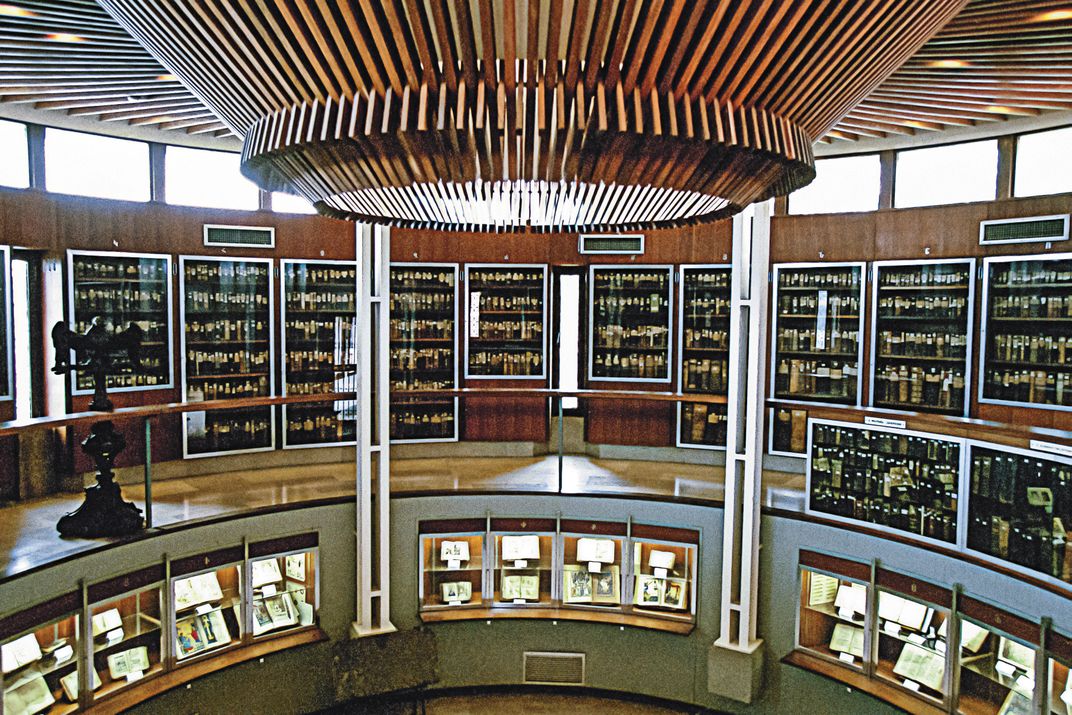

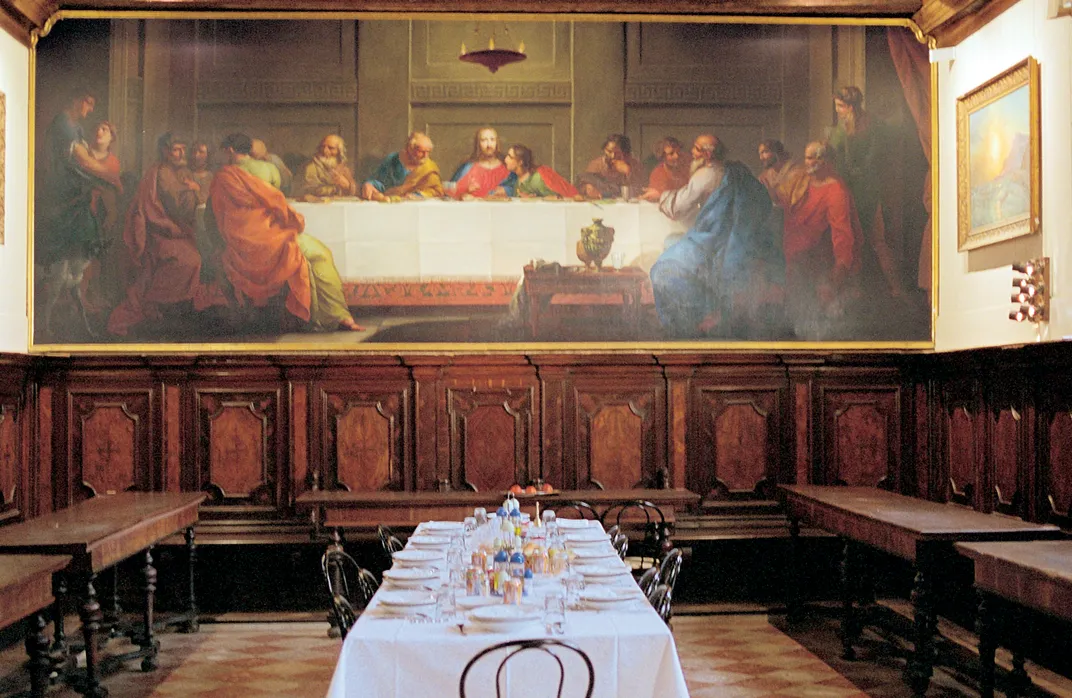

Lord Byron came here, possibly to escape his imbroglio of amours in the city. He rowed over from Venice to study Armenian with the monks, who were given political asylum and the island in 1717. By 1789, they’d started a printing enterprise known for producing works in many alphabets and languages, including Aramaic, Sanskrit and Gaelic. They’ve been here ever since, in a monastery filled with curiosities and with art, some mediocre and some interesting. I arrived at a serene cloister and with a few others followed a copiously bearded monk around the complex. Since I have an aversion to tours, I broke from the route and happily wandered AWOL for a while, discovering mummies, marble busts, rose-water liqueur made by the monks and a guest book where many visiting diasporic Armenians recorded their gratitude for this repository of their culture. What the monastery is most known for is the library of glass-fronted cases holding some of the monks’ 150,000 volumes, ranged around a room beneath frescoes of church elders who are reading books. There, you have to imagine Byron taking out volumes and trying to decipher various languages. I then found the dining room, with tables set for the monks’ silent supper, taken while overlooking, on the end wall, a huge painting of the Last Supper that must sober all their meals. San Lazzaro (Lazarus) previously was a refuge for sufferers of leprosy, as were other outposts in the lagoon. Paul Morand in his piercing memoir Venices credits the monks with importing Angora cats, but I did not see any sign of them.

I spent a night at Venice Certosa Hotel, a simple inn on La Certosa. The island is under development as a park, but right now is home only to a sailing school, a kayaking center and a boatyard for the repair of traditional small vessels. Kayaking in the lagoon looked fun and allows access to small islands. The inn’s restaurant was excellent, and the night should have been as deeply quiet as Torcello. However, the loose rigging on a sailboat near my window dinged all night. I departed early.

Across open water, the vaporetto speeds up to busy Burano, the island that explodes with color. What store offers house paint in magenta, ocher, grape purple, forest green? Why is no house painted the same color as the neighbor’s house on either side? “Oh, you’re doing yellow? Well, I’m going for Greek blue.” Burano—is there any place on Earth with as playful a palette? I’m getting off at the stop before—Mazzorbo. A small bridge connects them.

When I’m traveling, I always look at places with the question, Could I live here? Mazzorbo sets me dreaming of restoring a particular oxblood-red house with white trim right on the canal. Or is the yellow one more appealing? I don’t understand why Mazzorbo is not a coveted residential area for Venice. Once it was, like Torcello, a prosperous ancient settlement. The Latin name was Maiurbium, large urban place. Also like Torcello, it succumbed to fevers and silt. It languishes now, but one family has staked a big claim to a positive future for Mazzorbo. The Bisols, known for their many fine proseccos made in other parts of Italy, are reviving a plot of land where monks in earlier times made wines and farmed. By good fortune, the Bisols found the prized and rare Dorona grape—only five vines—on nearby Torcello. They discovered a few dozen others elsewhere in the lagoon, and from cuttings they started a vineyard. The family converted quayside buildings into Venissa, a small inn with an osteria and an innovative restaurant. The square pond of brackish water where the monks kept fish still exists in the shadow of the old campanile, last vestige of the religious complex. About 90 percent of the restaurant’s produce comes from the garden. How inspiring to see an idealistic project done just right. Theirs is a “km 0” restaurant, an Italian locavore designation signifying sustainable and homegrown. Dining at summer dusk on the edge of the vineyard in the quiet of these islands was bliss. And that golden wine! Maybe a bit of the setting sun melted into the glass. I was happy not to leave but to climb the stairs to a sloping beamed room with chic decor and a view of the canal. I hope this lively project lures others to the island and a little utopia flourishes again. Mazzorbo, otherwise, lies quiet in the lagoon time warp. Early walks on Burano before tourists arrive, around the perimeter of Mazzorbo, chats with women carrying groceries home from an expedition to market, a few people cultivating plots of tomatoes, onions and zucchini: a slow honey in this hive.

Just across the bridge to Burano, two bright wooden boats are moored near the vaporetto station. At the inn I was given the number of the skipper, who took me over to San Francesco del Deserto, the ultimate peaceful island. Only four Franciscans take care of the church, cloister and gardens. One of them guided me. His voice was so soothing that I wanted to curl up under a cypress and nap. He didn’t chatter, just let me look at the silvery, glazed-water views all around and watch a white egret that for a moment seemed like St. Francis returned. The monk related that when St. Francis visited in 1220, he performed his miracle of the birds. Throngs of them held forth with mighty song at the moment Francis wanted to pray. He told them to stop singing until he finished, which they did. It seems an easy miracle—I clap my hands and the cicadas always hush. Still, I hope it happened. Whether it did or not, the story survives, threading together all the days since on this small world amid other scattered small worlds.

The next day, as I waited on the quay for a water taxi, I remembered that many people consider “cellar door” the most pleasing sound in English. To my ear “lagoon,” with its hint of the moon, seems more beautiful. Or maybe this thought comes to me because the sound of “lagoon” has now gathered to itself vibrant marshy salt scents, a vast reflected sky, lone seabirds and the wavering and warp of time in secret places. The water taxi sped me to my hotel on the Grand Canal, back to the glorious, gaudy, fragile city I have loved for many years.

Navigating the Lagoon

Pick up an ACTV vaporetto map. On it, the routes of the many vaporetti, the people ferries that ply the lagoon, are numbered and color coded. At the train station, the airport, or anywhere there’s a vaporetto ticket kiosk, ask for the map called Linee di navigazione/Waterborne routes. Numbers on the boats correspond to the route numbers on the map. Note that the letter N designates night routes.

Vaporetto stations are all along the Grand Canal and at Fondamente Nove. If you’re unsure of your route, check with the attendant to make sure the ferry is going where you want to go. Rather than purchasing single tickets, you can buy an economical pass for a day or for several days. A three-day unlimited pass is 40 euros.

Motoscafi, private water taxis, are plentiful. There’s usually a stand near a vaporetto stop. Water taxis are expensive, but sometimes time is more valuable than money. From the airport to Torcello, I paid 130 euros. From Mazzorbo to the Grand Canal, I paid 80 euros.

Across the River and Into the Trees