Staring at the Sun: It’s NOT a “Mass of Incandescent Gas”

Solar astrophysicist Mark Weber presents new research about that “miasma of incandescent plasma” at the Air and Space Museum

![]()

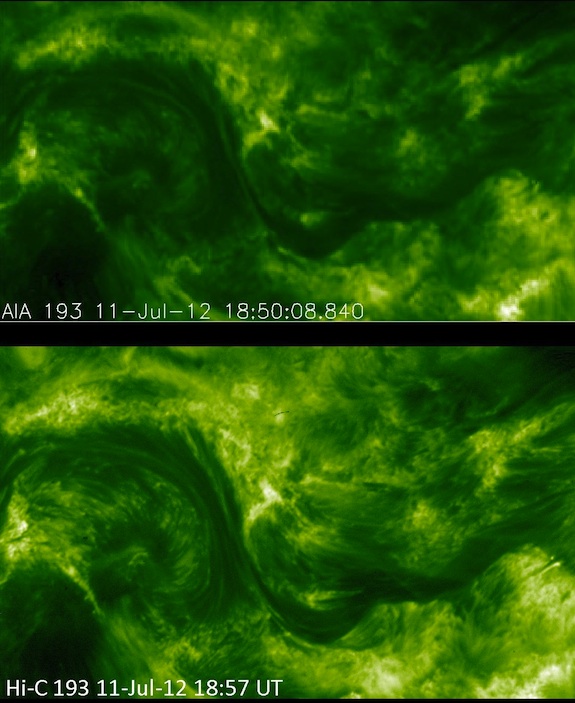

Hi-C captured the most detailed images of the sun’s corona in July 2012. Courtesy of NASA

When the band They Might Be Giants re-recorded the 1959 song “Why Does the Sun Shine?” for its 1993 EP, they played to a much-repeated piece of science fiction. The track, subtitled “The Sun is a Mass of Incandescent Gas,” gets some basic sun science wrong. “A gas is a state of matter in which the material is not ionized, so all of the atoms still have all of their electrons and really the sun’s gas is in a state called plasma,” says Smithsonian astrophysicist Mark Weber.

Though scientists had known this for quite some time, once it was pointed out to the band, it promptly issued an updated track in 2009, “Why Does the Sun Really Shine? The Sun is a Miasma of Incandescent Plasma.”

But Weber, who will present Saturday, November 17 at the Air and Space Museum, says, that’s not all that’s new in the world of sun science.

“The sun is a very interesting object of study,” he says. “People shouldn’t assume that we’ve moved on from the sun.”

The sun does all kinds of things, Weber says, “it has all sorts of different features and all sorts of different events and phenomenologies.”

One of the phenomena currently on the minds of solar researchers is why the corona, the plasma atmosphere surrounding the surface of the sun, is so incredibly hot. “All of the energy from the sun comes from the interior of the sun and so sort of a simple, thermodynamic interpretation would expect the temperature of the sun to decrease as you go further and further away from the core,” says Weber. And that’s mostly true, he says, with one notable exception: “There’s a point we call the transition region, where the temperature rockets from a few thousand degrees at the surface of the sun up to millions of degrees in the corona.”

Weber’s particular focus is determining precisely how hot the corona is. Scientists are also trying to understand what processes might be heating the plasma to such extremes. Weber says, “There’s a lots of great ideas, it’s not that we don’t have any idea what’s going on,” adding, “What might be heating one part of the corona, like say a single standing loop of plasma, might be very different from what’s going on, say, in an active region, which are these areas over sun spots that are really hot and have all kinds of eruptions happening all the time.”

Between the transition region and the erupting sun spots, Weber seeks to show people that the sun is anything but static. “A lot of people have this idea that the sun is a yellow ball in the sky and that we understand everything about it.” But he says the sun is incredibly dynamic and has been dazzling scientists for hundreds of years. In fact, in the 19th century, scientists believed they had discovered completely new elements while studying the spectral emissions from the sun. “They were seeing spectral lines that they couldn’t identify,” says Weber. “That’s because these lines are coming from very highly ionized ions, which implies a very high temperature.” But at the time, says Weber, “No one expected that the temperature of the atmosphere of the sun was so much hotter, that just didn’t occur to people.” And so they named the new element–which was actually highly ionized iron–coronium.

Comparing older, less detailed images of the corona with Hi-C’s newer, more detailed images, researchers were able to see more than ever before. Courtesy of NASA

Now of course, scientists are capable of collecting far more sophisticated analysis, including from a recent rocket mission called the High Resolution Coronal Imager, or Hi-C. “We got to see a small section of the solar atmosphere at a higher resolution than anyone had ever observed before,” says Weber, who was involved in the project. One of the things they were finally able to see was that what had once been thought to be single loops of plasma were in fact multiple intricately braided strands. Weber says, “We could even see the braiding sort of twisting around and shifting, as we were watching the sun with this rocket flight.”

With all the new imaging available, Weber says people are amazed to discover how beautiful the sun truly is. He says, “You’re just sort of overwhelmed by how much is going on.” And, he adds, “It’s a fascinating area to do physics in!”

As part of the Smithsonian’s Stars Lecture Series, Mark Weber will present his lecture, The Dynamic Sun at the Air and Space Museum, Saturday, November 17 at starting at 5:15 p.m.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Leah-Binkovitz-240.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Leah-Binkovitz-240.jpg)