Q+A: New Yorker Writer Adam Gopnik Talks American Art, Writing and Going Back to School

The critic will discuss “What Makes American Art American” Wednesday at the American Art Museum

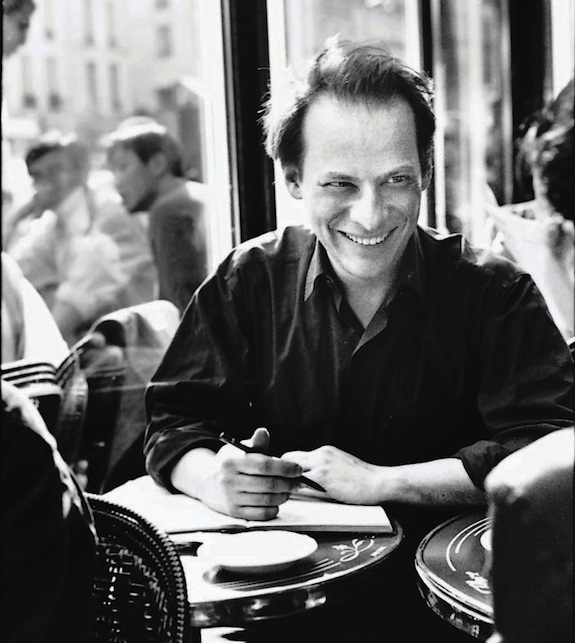

Critic Adam Gopnik will be speaking at the Smithsonian American Art Museum on Wednesday, October 10th. Photo courtesy of the museum

Adam Gopnik is a staff writer at The New Yorker. An essayist in the grand tradition of E.B. White, Gopnik brings a studied, yet enthusiastically amateur, eye to everything from baseball to art to politics. Published in 2000, his book Paris to the Moon, grew out of his time spent writing for The New Yorker‘s “Paris Journals.” He has won three National Magazine Awards for his essays and written a number of books, including Through the Children’s Gate, Angels and Ages: A Short Book About Darwin, Lincoln, and Modern Life and The Table Comes First: France, Family, and the Meaning of Food.

Gopnik, 56, was born in Philadelphia and raised in Montreal. He graduated from McGill University and completed his graduate coursework at the Institute of Fine Arts, New York University. In 1990, he curated the exhibit “High/Low” at the Museum of Modern Art.

This Wednesday, he will be lecturing at the Smithsonian American Art Museum as part of the Clarice Smith Distinguished Lectures in American Art series. We talked by telephone with the writer from his New York apartment about American art, his writing career and his plans to go back to school.

The lecture for Wednesday’s talk is titled “What Makes American Art American?” That’s a lot of ground to cover, can we have a preview?

A few years ago I gave a keynote address when the Smithsonian American Art Museum reopened and I tried to talk, then, about the difficulties of making sense of the idea of American art. In other words, you can take a strong position. My little brother Blake who is the art critic for Newsweek’s Daily Beast insists that it’s kind of narrow and shallow chauvinism to talk about American art having special qualities, that to say that there is some essence that passes from John James Audubon to Winslow Homer to Richard Serra, we’re deluding ourselves. Art is inherently cosmopolitan and international and trying to see it in national terms betrays its essence.

On the other hand, you have very powerful arguments that there are specifically American traditions in the visual arts. You may remember that Robert Hughes in American Visions made that kind of case. I want to ask again how can we think about that, how should we think about it? Does it make any sense to talk about American art as a subject in itself?

The other question that I want to ask, and it’s the one I’ve added to this meditation since last I spoke in Washington is what about the question of drawing boundaries? One of the things that’s been specific about people looking at American art for a long time is that we more easily include things like furniture—think of Shaker chairs—the decorative arts, cartooning in our understanding of what American art is. If you look at the early collections of American art in museums, for instance at the Metropolitan Museum here in New York, you see that they very easily broke those lines between the fine and the decorative and applied arts in ways that they weren’t doing in collections of European art at the same time. That was done originally, as a kind of gesture of diminution. You could look at American art as a kind of lesser relative, still something that was cadet and on its way. And so you could include lots of seemingly extraneous material sort of on an anthropological basis. We were looking at ourselves anthropologically. As that’s persisted, it raises another set of questions. Is that enriching? Is that evermore legitimate? Is that a kind of model that should be allowed to sort of infect the halls of European art? That’s the new question that I’m going to try to raise in addition to rehearsing, because I don’t think it ever gets stale, the fundamental question of what we mean when we talk about American art.

It’s hard not to think of art divided along those traditional, national lines.

That’s the natural way to see it, and I think that’s the right way to see it. I think we can talk about continuities in American art as we can talk about real continuities in French art or, God help us, in English art. But they’re not self evident, they’re not transparent.

Trumpeter Swan, John James Audubon, 1838.

So what defines American art?

The title I gave to the last lecture was in terms of two poles: “The overabundant larder and the luminous oblong blur.” On the one hand, you have the overabundant larder, you have this sense of plenty. It’s best exemplified in Audubon’s work. If you think about what Audubon set out to do, it was something completely new. He was trying to make a picture of every single bird and every single four-legged beast in North America. He was totally omnivorous and democratic, there’s no sequencing, there was no, “these are the noble beasts and birds and these are the lesser beasts and birds.” It’s everything at once. That sense of inclusion, of inspection, of the complete inventory, that’s a very American idea. In obvious ways it runs direct from Audubon to someone like Andy Warhol, that same omnivorous, democratic, Whitman-like appetite for the totality of experience without hierarchy within it. That’s why for Warhol, Elvis and Marilyn are the holy figures, rather than holy figures being holy figures.

And against that you have what I call, the luminous oblong blur. That comes from an evangelist back in the 1920s, who said once when someone asked what does God look like to you, “Like a luminous oblong blur.” That’s the sense that transcendent experience, spiritual experience, religious experience is available, it’s out there. W.H. Auden once said that it’s the deepest American belief that when you find the right gimmick, you’ll be able to build the new Jerusalem in 30 minutes. It’s that sense, that that transcendent, powerful, sublime experience is there for the asking. You find the luminous in something like 19th century landscape and it runs right through to Mark Rothko and Barnett Newman and the sublime abstract painters of the 1940s and 50s. They think what they’re showing you is not pain, but paradise, or some version of it. That’s a very powerful tradition in American art as well.

Called “the finest book on France in recent years” in the New York Times book review, Paris to the Moon details the fabulous and mundane realities of life in Paris.

I read that you said, your work is about a longing for modernity in a postmodern world. I was wondering how your work fits into this trajectory of American art?

Did I say that? That’s a bit full of itself isn’t it? I think it’s true, I apologize if it seems pompous. What I meant by it, when I said it and I’m sure I did, is that the art and civilization that I cherish and love is that of modernity. It’s the essentially optimistic, forward-looking and in some way ironic way but in some deep sense confident world of Paris and the Cubists of 1910 or Pollock and the abstract expressionists in 1947. It’s not that these worlds were without deep flaws and a sense of tragedy but they believed in a future for art. They believed in the possibility of lucid communications. They believed in the possibility of creativity. We live in a postmodern age in which those things themselves–lucidity and creativity–are all thrown in essential doubt. In that sense, that’s what I meant in longing for modernism in a postmodern age.

In terms of my own work, I think that one of the great privileges I have had writing for The New Yorker, but it’s also in a sense an extension of the kind of sensibility I happen to have, is that I like to do lots of different kinds of things. I hate this sense of specialization. I have an appetite for lots of different kinds of experience. One of the pleasures of being an essayist as opposed to a specialist or an academic is that you get to write about lots of different kinds of things. It’s no accident, then, that The New Yorker as an institution is kind of unique to America. There’s no French New Yorker, there’s no British New Yorker because it relies on the notion that you can write with authority without having any expertise about lots of different things. That idea of the amateur enthusiast is one that is very much a part of a certain kind of omnivorous American tradition.

How has studying art history helped you go on to examine all these topics?

I just was going back on a sentimental journey a week ago to Montreal to McGill University, where I did my undergraduate work in art history and it was sort of heartbreaking to me because they don’t have an art history department anymore. It’s now something like communications and visual history or something very postmodern and up-to-date. I think they still teach art history but they teach it within this much broader, anthropological context. The point is, I had this wonderful mentor-professor in psychology, which is what I started out in. I was torn about whether to go into art history or stay in psychology and I was agonizing over it with the self-importance that you have at 22. He calmed me down and he said, listen, this is not an important decision. An important decision is whether you’re going to go into art history, psychology, or dentistry. That’s an important decision because it will make your life very different, but decisions that seem really hard aren’t very hard because it means you’ve got something to be said on both sides. I probably wouldn’t have been very different had I taken the turn to psychology rather than art history.

I do think that the habit of looking and the practice of describing (which, I think is sadly decayed in art history as it’s practiced now, but as far as I’m concerned it’s at the core of it and is what all the great art historians did) I think that is a hugely helpful foundation for anybody who wants to be a writer. In fact, I’d go farther and actually even say that it’s a better foundation than creative writing because to confront something as complicated and as many-sided and as non-verbal as a great work of art and try to begin to find a language of metaphor, evocation, context and historical placement for it, is in some respects the hardest challenge that any writer can have.

I completely agree, and having studied it, I was heartened to hear you had an art history background, though I know you didn’t complete the Ph.D. program at New York University.

I didn’t, I’m ABD (All-But-Dissertation) I guess the year…I did my orals in 1984, so you can figure it out, but it’s almost 30 years now. I’ll do it someday. I’m the only one, of five brothers and sisters, without a PhD. Some day I’ll go back and get it. When I was studying art history back in the 70s and 80s it was still very much an old-fashioned disciplined. You mostly did archival research and most of the professors did iconography, just puzzle solving about what’s the little dog mean in the righthand corner of the picture. Now, of course, it’s been totally revolutionized and modernized and I think it makes you long for the old archival, iconographic tradition which seemed terribly stultifying when I was part of it.

I no longer write regularly about the visual arts, though I try to write often about them when something stirs me. But I still feel, if you’ll allow me a semi-sentimental moment, that there’s no rush of excitement as great as that of walking into a great museum and being aware that you’re in proximity to beautiful things.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Leah-Binkovitz-240.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Leah-Binkovitz-240.jpg)