James Borden Doesn’t Just Build Clocks, He Creates Sculptures that Tell Time

At the 32nd annual craft fair, the art and craft of the traditional clock takes on a whole new tick tock

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/61/37/613736ea-6b05-4230-a6df-126e6a779045/clock7.jpg)

Clockmaker James Borden and his sculptural wooden timekeepers make a compelling argument for the humanities. The Iowa-based craftsman attended Dana College, a small liberal arts school in Blair, Nebraska, where he took classes in history, art and science. “It was great for me because it involved integrating ideas, not studying just one,” says Borden. “You saw how all these different areas of thought connect with each other—just like a clock, which involves scientific principals of laws in motion, and physics and design.”

Borden had always loved clocks and other mechanical objects, and had even grown up in Rockford, Illinois, which was then home to a vast private collection of time-measuring devices. He'd only tinkered with them as a hobby, but his varied coursework—reading about the history of American clockmaking, for example, to learn how early New England clocks were fashioned from wood, and seeing the famous Glockenspiel tower clock while studying abroad in Munich—inspired him and a friend to take the plunge and build their own for a class project.

“We did a study on timekeeping, and we made this huge clock with wooden gears,” says Borden. “For me, that just got things rolling. “

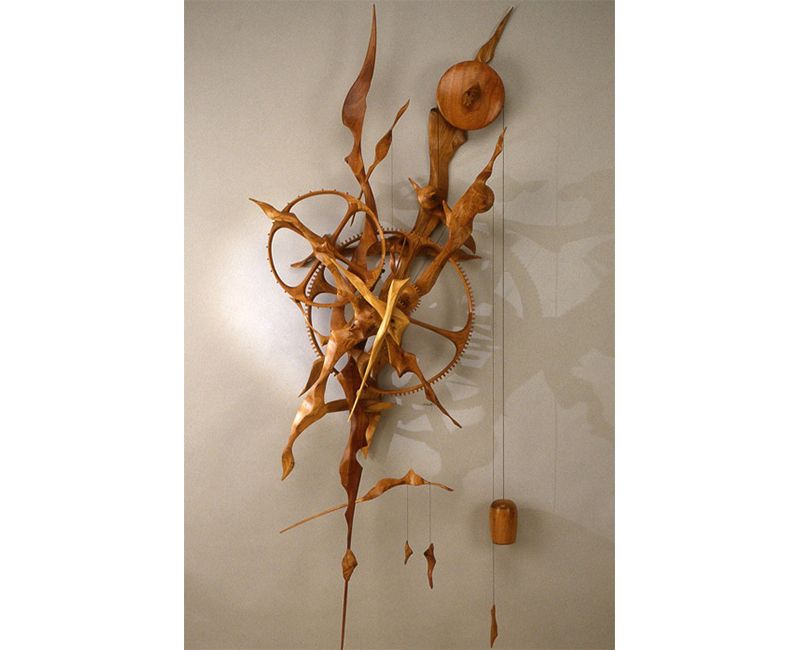

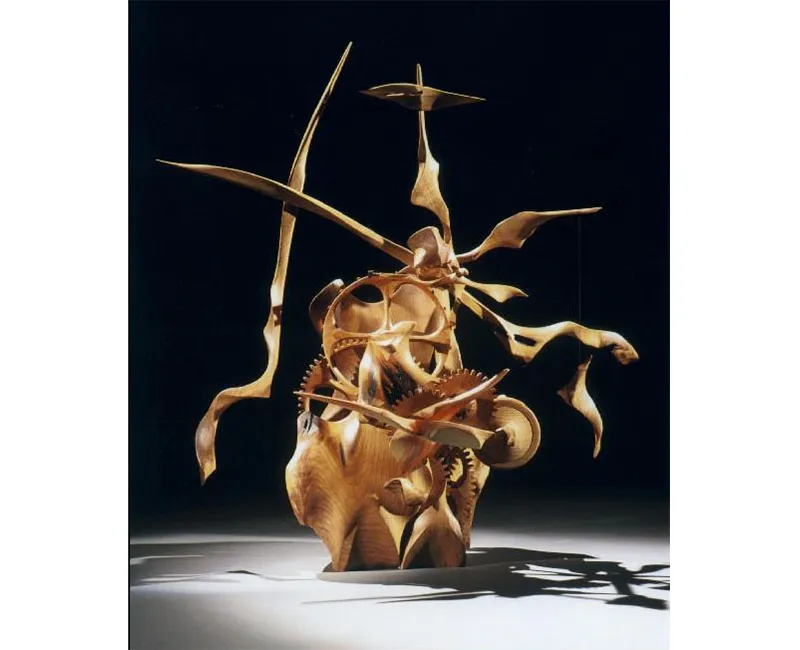

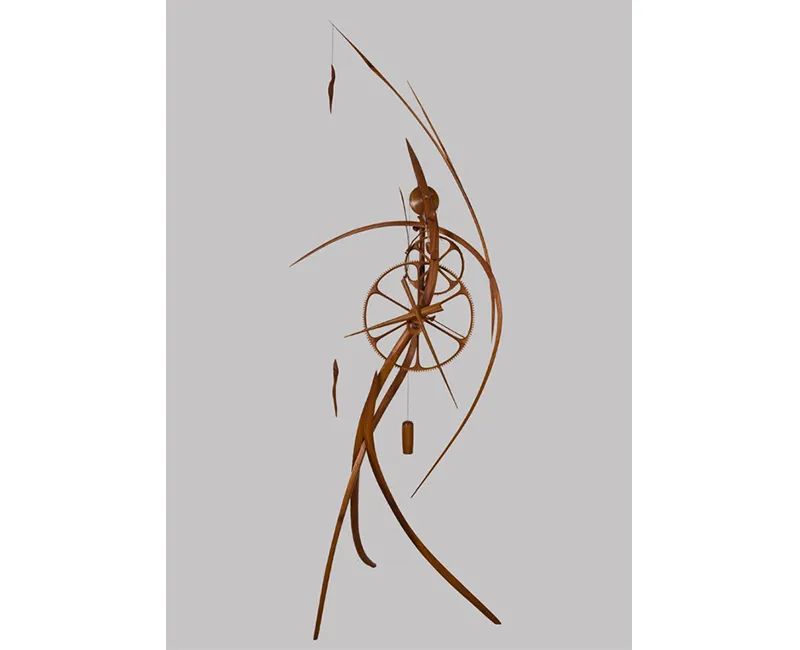

Now more than 30 years later, Borden is known nationwide for his business, Timeshapes, which sells large, hand-carved wooden clocks with sweeping levers, wheels and exposed gears whittled from black walnut, cherry wood and hickory. This week, his work will be once more displayed among other fine objects at the Smithsonian Craft Show, an encore to last years’ event in which he participated for the first time and won two prizes including the First Time Exhibitor Award and the Gold Award.

Borden finished his first clock in 1980, and spent the following year after college in his parents’ basement, building pieces that included a unique Victorian clock with no box, dials, face or numbers—an aesthetic forerunner of his future works. But despite his burning interest in the machines, Borden didn’t plan to work with them for a living.

Borden decided to attend Wartburg Theological Seminary in Dubuque, Iowa, where he met his wife, Barbara. About midway through the program, the erstwhile craftsman changed his mind; he realized his passion for clocks had turned into a lifelong pursuit. Borden opened up a clock shop, where he repaired and restored antique timepieces while attending seminary part-time. He graduated, but was never ordained. After their marriage, he and Barbara lived above the clock shop.

Gradually, Borden shifted away from fixing clocks to designing them. At first, his wooden clocks steered close to the side of tradition. But he later started fixating on the objects’ spinning mechanisms, and became intrigued with the idea of making a standing or hanging clock that didn’t have cabinets to shield its gears. He stretched out different components—building larger gears, levels, pendulums and hands—and got rid of any other part of the clock that didn’t, well, make it tick. Soon, the clocks grew to have more refined shapes, with curving, graceful arcs and large gears and levers that swung and spun free of any framework. “I consider them to be wooden kinetic sculptures that are an expression of time through shape and motion,” says Borden.

Borden and his family eventually relocated to Minnesota. There, he started to display his clocks in public settings, like malls, and began exhibiting at local and regional craft shows. A friend advised him to attend the American Craft Council's show in Baltimore, Maryland, which he did to great success. "The Midwest was a much more limited market, I guess, and it was hard for me to make sales," says Borden. "Then the Baltimore show really broke things open."

From then on, Borden's business took off; he now sells his clocks at juried craft fairs and exhibitions across the country, and also accepts commissions for private buyers. “Ninety-five percent of them go into peoples’ homes,” says Borden. “They can be sometimes fairly large clocks, I have one now that I’m finishing up for a home out in Massachusetts. The total clock sculpture is about 17 feet wide, and it hangs on the wall.” Each item is completely hand-hewn, says Borden, after carefully selecting the wood. He makes about 10 to 15 clocks a year, and sells them for prices ranging from $5,000 to $10,000 dollars a piece.

This year, Borden, who is now the father of two college-aged children and lives in Sibley, Iowa, with Barbara, will once again sell a range of clocks—free-standing, wall-mounted, large, small— at the Smithsonian Craft Show. Each purchase is unique, he says; they all "turn out a little different because every piece is designed and made by hand. They're not done with any kind of mass production techniques or patterns."

Instead, Borden's works are culmination of love, skill and time. "My wife likes to say that making a clock takes me my whole life,” says Borden. “All my background experience and learning and study goes into each one.”

The Smithsonian Craft Show opens at the National Building Museum on Thursday, April 10, and will run until Sunday, April 13. Tickets are available for purchase online. Admission is $15 a day, $25 for a two-day pass. Proceeds support the Smithsonian Women's Committee Grants Fund.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Fawcett-Bio.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Fawcett-Bio.jpg)