Babe Ruth Hit a Home Run With Celebrity Product Endorsements

The Great Bambino was one of the first athletes to be famous enough to require a publicity agent to handle his affairs

He was the first baseball player to hit 60 home runs in a single season and later his record of more than 700 career homers made Babe Ruth seem nearly superhuman.

In fact, researchers at Columbia University became so entranced by his knack for setting records that they conducted an efficiency study on the Sultan of Swat and found that he was actually more productive and powerful than the average person—working at 90 percent efficiency compared to the average 60 percent.

By the end of his career, he held 56 records and was among the first five players inducted into the Baseball Hall of Fame.

This summer a new exhibition at the National Portrait Gallery chronicles Ruth’s professional and personal life as part of the museum’s “One Life” series, which has delved into the lives of such luminaries as Martin Luther King Jr., Sandra Day O’Connor, Elvis Presley, Walt Whitman, Dolores Huerta, Ronald Reagan and Katharine Hepburn.

“He could be loud and brash and overbearing, but the old players I talked with invariably smiled when they remembered Ruth and spoke fondly of him,” wrote Ruth’s biographer, Robert W. Creamer for Smithsonian magazine in 1994. “Once, probing for an adverse opinion, I asked an old-timer, ‘Why did some people dislike Ruth?’ ‘Dislike him?’ he said. ‘People got mad at him, but I never heard of anybody who didn’t like Babe Ruth.’”

Ruth’s unprecedented athletic prowess pushed him into the public’s consciousness in a way never seen before. He was one of the first to be famous enough to require a publicity agent to handle his affairs. The agent, Christy Walsh, was responsible for arranging the efficiency studies at Columbia that were eventually published in Popular Science in 1921.

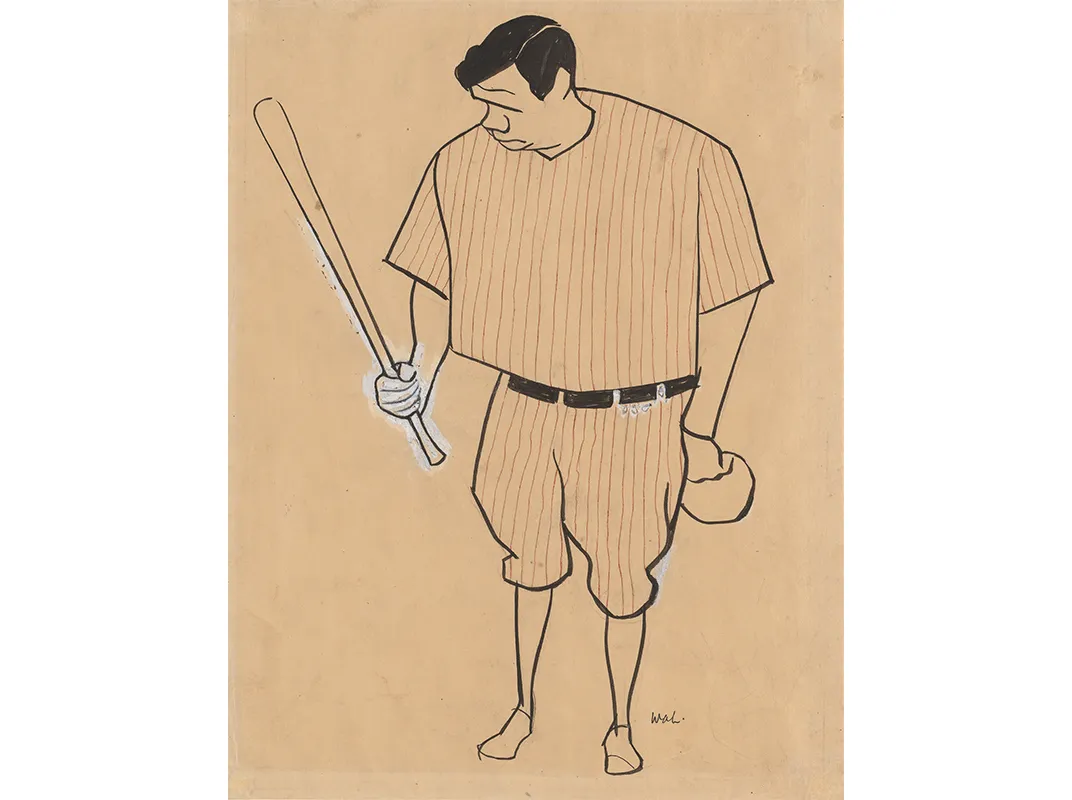

Walsh was also involved in leveraging the Babe’s fame into fortune. In one of the first contracts of its kind, Walsh secured Ruth’s permission to tack his name on a ghostwritten sports column. Later, he further commodified Ruth’s name and image in some of the first celebrity-endorsed product marketing. A box of “Babe Ruth Underwear” and a wrapper from “Ruth’s Home Run” chocolate are both on display in the exhibition.

While the Babe’s athletic achievements were known around the world, his life outside the stadium remained unreported. Unlike the ubiquitous tabloid coverage of today’s celebrities, Babe’s personal life was just that—personal. In that era reporters met Ruth, who led a tabloid-worthy life wrought with affairs and an illegitimate child, at the baseball field and let him leave in peace.

“He wouldn’t have lasted in this day and age,” says historian and curator of the exhibition James G. Barber, noting today’s media obsession with celebrities and their personal lives.

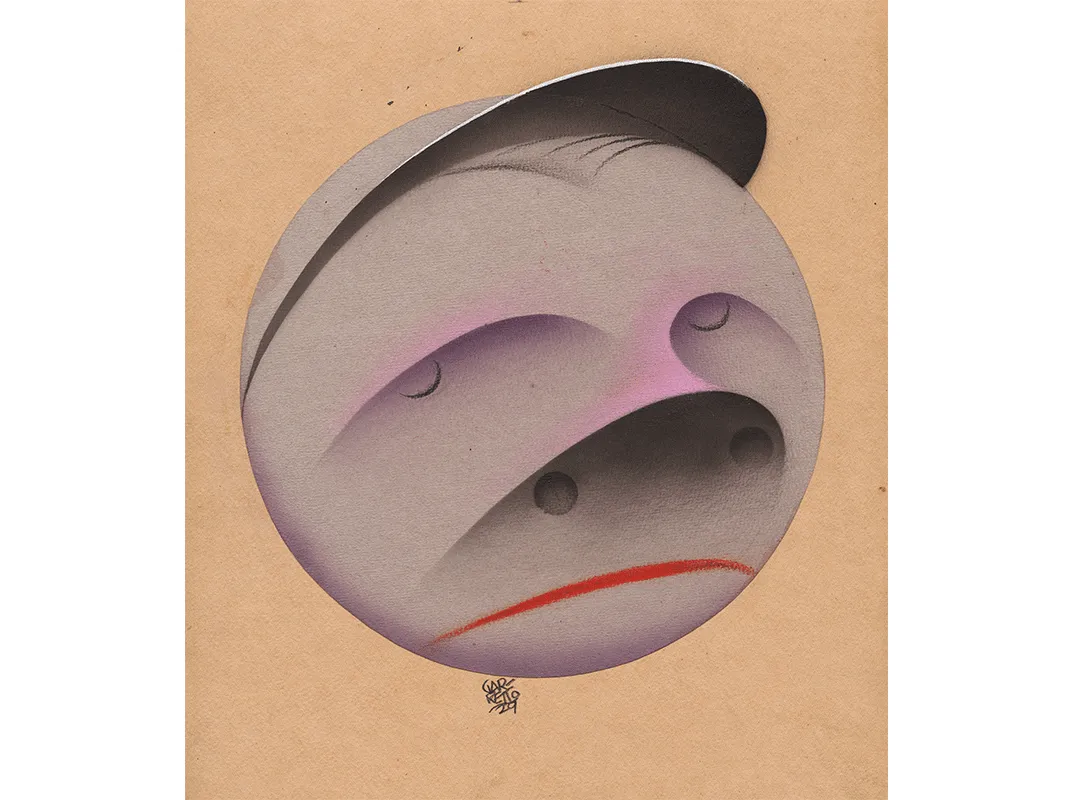

Although little is known about Ruth’s life outside the stadium besides his penchant for beautiful women, Barber aimed to paint a near-complete picture of Ruth—one as family man, philanthropist, and, of course, enviable baseball player.

“My great interest with Babe Ruth is his personal life. That’s something that’s hard to capture, it’s hard to recreate,” says Barber. But the show's prints, photographs, memorabilia and advertising materials deliver a compelling narrative.

A photograph of Ruth with his wife and daughter shows Ruth’s softer side, though it was later revealed that the young child in the picture was that of one of Ruth’s mistresses.

In another photograph from 1926, Babe Ruth poses with a group of children at an orphanage called St. Ann’s Home. A young child in the photo holds one of those “Ruth’s Home Run” chocolate wrappers.

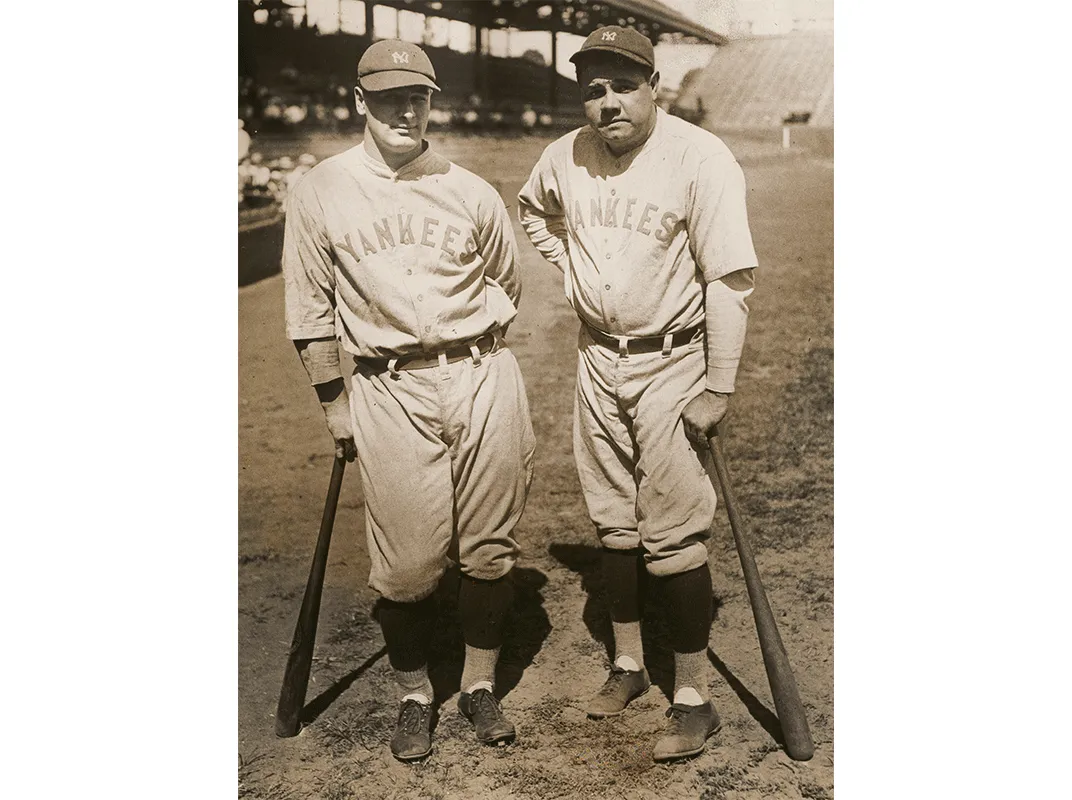

Few studio photographs exist of the Babe, but in one sepia-toned image from 1920 Ruth wears his signature Yankees uniform and poses with a baseball bat. Just under his knee is his signature in perfect script, a skill for which Ruth took great pride.

“His life was a mess but his signature was letter perfect,” says Barber.

In addition to the photographs of Ruth on the field, and the products marked with his round face, the exhibition features a baseball bat he once gifted to the mayor of Chicago.

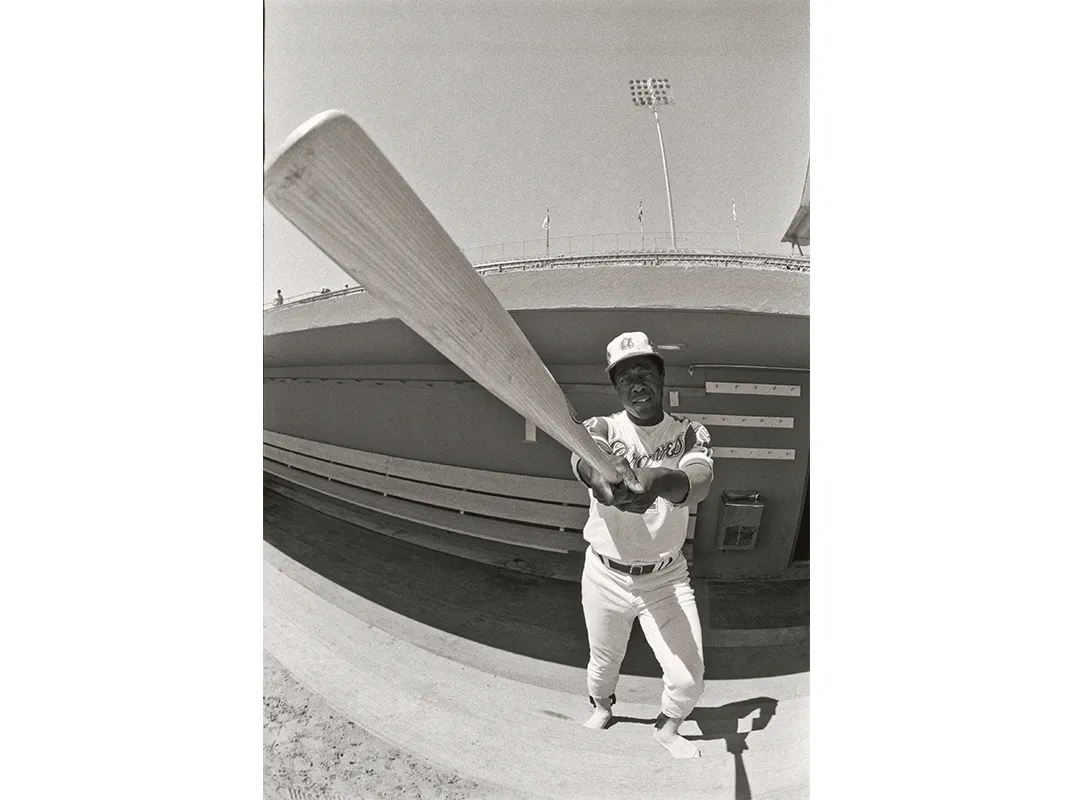

At the end of the exhibition are images and paraphernalia from Ruth’s funeral, which in 1948 attracted tens of thousands of fans to St. Patrick’s cathedral in New York. Other photographs feature baseball players who eventually broke some of Ruth’s records such as Hank Aaron, Roger Maris and Whitey Ford.

“He was the best player who ever lived. He was better than Ty Cobb, better than Joe DiMaggio, better than Henry Aaron, better than Bobby Bonds. He was by far the most flamboyant. There’s never been anyone else like him,” wrote Creamer.

“One Life: Babe Ruth” continues through May 21, 2017 at the National Portrait Gallery.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/DSC_0154.JPG.jpeg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/97/f2/97f291d6-8066-40e0-914c-227ce5a748c9/npg_2011_11-ruth-rweb.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/8c/04/8c04f9fd-9016-483c-a19d-6c1ef98fa6e5/ruthportraitweb.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/50/d3/50d34612-3275-4f8d-a425-4c8270dee7f3/whiteyweb.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/b3/91/b391983d-3a47-4df5-8c61-4913405c70ae/npg_93_350-ruth-rweb.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/DSC_0154.JPG.jpeg)