The Hottest New Accessory for Songbirds: Tiny GPS-Enabled Backpacks

Peter Marra and Michael Hallworth of the Smithsonian Migratory Bird Center test a groundbreaking device that tracks birds’ migrations

:focal(1363x392:1364x393)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/40/38/4038de36-5cb1-4fd8-8c9e-bd0b6c1942d6/bird2.jpg)

Olive green with black stripes along its chest, the dainty ovenbird weighs just over 20 grams and fits easily in the palm of a person’s hand. Every year, the tiny songbird treks thousands of miles, making an annual migration from its breeding areas in the Northern United States and Canada to the warmer climes of Mexico, Central America and the Caribbean. Because the ovenbird is so small, there hasn’t been a way to document the path of its extensive journey—until now.

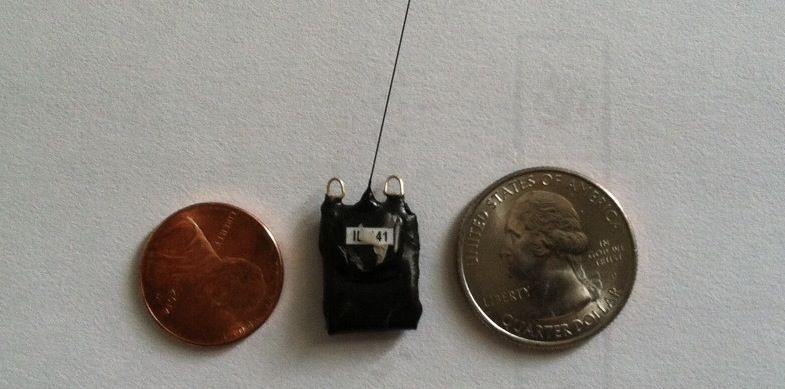

The Smithsonian Conservation Biology Institute’s Migratory Bird Center, led by Peter Marra, was the first to test a groundbreaking device that comes in the form of a miniature backpack equipped with a GPS tag. The device is the lightest ever produced, weighing less than a gram, so smaller animals like the ovenbird are still able to wear it. The precision of the device is also unique—offering location measurements within 10 meters compared to the much broader estimates spanning 150 to 200 kilometers that previous technology provided.

“Tracking an animal this small, with a device of this size, and with this degree of precision has never been done,” says Marra in a release. Before the invention of this backpack, the smallest GPS tracker was 12 grams, designed for animals no smaller than 250 grams themselves. The new tracker works by automatically turning on for 70 seconds at a time, during 8 to 10 different points along a bird’s trip.

Marra and his colleague Michael Hallworth recently announced their breakthrough in Scientific Reports, highlighting its potential to help refine conservation efforts. If scientists are able to clearly delineate a bird’s path, the hope is that they can better target key threats along its route including deforestation.

Nearly twenty years ago, while he was working on his Ph.D in ecology at Dartmouth, Marra first began thinking about different ways to monitor birds’ migratory patterns, as a means of promoting effective and targeted conservation. Back then, while he reached out to cell phone companies and other partners, the technology didn’t quite yet provide the kind of functionality that Marra envisioned.

“In the past ten years, the types of devices that are out there and the sizes of devices have really changed,” says Marra. He collaborated with Lotek Wireless, an Ontario, Canada, company that builds wildlife monitoring systems, to craft this iteration of the backpack. “Developing the device was all about tradeoffs,” he says, “Like weight vs. power. We were pleased to test a design that met those needs.”

One major requirement is that the device had to be light enough, no more than five percent of the wearer’s body weight. Additionally, as they travel, birds put on extra fat and muscle on their chests, so it needed to accomodate these changes while allowing wearers to freely use their wings. Given these considerations, Lotek developed the backpack, which is able to stay on the bird throughout its travels and is attached with a harness that doesn’t hurt the animal.

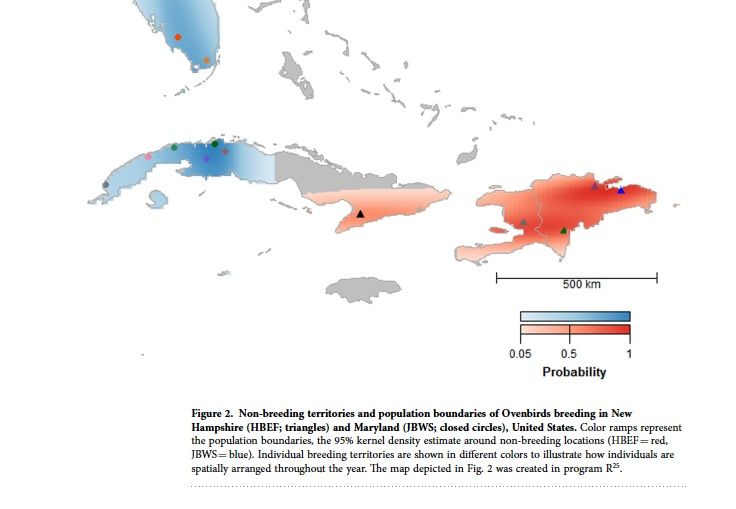

In the study detailing the tool’s use, Marra and Hallworth attached the backpack to 24 ovenbirds, 10 from Maryland and 14 from New Hampshire. The birds wore the trackers for almost a year from June 2013 to April and May 2014. Fifteen of the trackers remained intact at the end of the birds' journeys, revealing new, unprecedented data about their migratory paths.

The two sets of birds ventured south, as expected, to tropical regions during their non-breeding period in the winter months. However, the destinations they respectively selected did not overlap. The birds from New Hampshire elected to spend their time in Haiti and the Dominican Republic, while those from Maryland chose Florida and Cuba.

This data not only provides an in-depth look into where ovenbirds go, but also how disparate those places can be—underlining the importance of conservation that’s tailored to different areas. For example, while Florida may not face significant deforestation right now, Haiti is nearly 95 percent deforested, notes Marra. Scientists now have more data that pinpoints particular habitats the birds frequent, enabling them to identify and prioritize locations in need of support and cultivation.

“An accurate, miniature transmitter is the holy grail of wildlife science,” says John Marzluff, professor of wildlife science at the University of Washington of this breakthrough, “With such a device we might learn secrets of where animals go, what environments they require, how long they live, and what factors affect their reproduction and survival.”

“Their findings are revolutionary, not only because of what they have learned about ovenbirds but more importantly because they have shown the rest of science a useful path to the grail. The transmitters used in this study will be widely used on other migratory species who are faithful to breeding grounds,” he says.

“This looks exciting. Small GPS loggers have been used in a large variety of applications although size has always been an issue,” notes John Eadie, professor of wildlife, fish and conservation ecology at the University of California, Davis. Eadie also categorizes such progress as indicative of growing applications of technology for wildlife science. “It used to be that field ecology was done with a notebook, a couple of sharp pencils and a good set of binoculars. Not any more.”

Marra emphasizes that this invention is just the beginning of how innovations in technology can advance the scientific study of migration. Currently the device can only capture 8 to 10 points of a bird’s location along its migratory path. Ideally, Marra hopes to get to a version when it will be able to measure fifty points.

“This is not where we need to be, but it’s a step in the right direction,” he says, “The more points we have, the better off we are.” A second limitation that he, Marzluff and Eadie identify is the need to recapture the birds in order to obtain the GPS data. For future iterations, Marra aims to create one that can communicate with satellites remotely and in real-time, so that data can be directly transmitted without the lag time and uncertainty of recapture.

The next birds that Marra hopes to track with this tool include the wood thrush, rusty blackbird and red knot—although he is open to examining any other threatened species to further understand why population dips are taking place. “One-third of birds species are declining and we don’t know why,” he says. This device gets him and other wildlife scientists closer to figuring out these reasons and focusing conservation to prevent such declines.

UPDATE 6/19/2015: This article has been updated to clarify that Lotek Wireless of Ontario, Canada designed and developed the miniaturized GPS technology. The scientists were the first to test the devise.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/profile.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/profile.jpg)