Frances Benjamin Johnston’s Garden Legacy: New Finds from the Archives

Research has helped identify glass lantern slides within the collection from the famed photographer’s garden images

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/20120807081010FBJ_Thumbnail.jpg)

In 1897 in an article published in the Ladies Home Journal, the female photographer and businesswoman Frances Benjamin Johnston offered a guide to her success in an essay titled ”What a Woman Can Do With a Camera.” As it turns out, if the woman happens to be Frances Benjamin Johnston, well then, she can do quite a lot.

Over her lifetime, Johnston amassed a body of work that included more than 1,100 glass lantern slide images of public and private gardens. Created at a time when color was not readily rendered from the camera, colorists painstakingly hand-painted each of her slides, known as glass lantern. She used them to deliver lectures on a travel circuit that covered topics including, Old World gardens, the problems of small gardens and flower folklore during the 1920s and 30s. Her gorgeous images provide a unique glimpse into the backyards of some of her wealthiest patrons, including Frederick Forrest Peabody, George Dupont Pratt and Edith Wharton. Recently, a researcher identified 23 (and counting) unlabeled images in the Smithsonian collections as works of Johnston’s, helping shed light on the prolific career of an exceptional woman and the complexity of her work.

Johnston studied art in Paris and learned photography here at the Smithsonian under the tutelage of Thomas Smillie, the Institution’s first photographer. During her lifetime, garden photography was mostly ignored by the art institutions. As Ansel Adams built a successful career with his images of American landscapes, Johnston struggled just to get her name published alongside her photographs in the home and garden magazines of the era.

“Garden photography, as a genre, is not one that people, even in art history, really think about,” says Kristina Borrman, a research intern with the Archives of American Gardens. Borrman, who discovered the cache of Johnston’s images in the Archives, says garden photography represents another side of the American narrative and often reveals the fault lines of class division. Rather than constructing the myth of the frontier, “it’s the meticulously mannered frontier, it’s the manipulated space and that is such a beautiful story, too.”

Though Johnston left her collection to the Library of Congress, the Smithsonian acquired many of her images through a 1992 donation from the Garden Club of America that included 3,000 glass lantern slides from the 1920s and 30s, as well as 22,000 35mm slides of contemporary gardens.

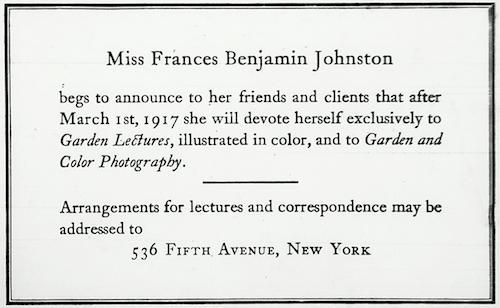

Ever the business woman, Johnston maximized her income whenever possible, writing to notable society members in each city advertising her photographic services. These commissioned images from her wealthy patrons document the lavish gardens of the era, from country estates to urban retreats.

She was able to capture the height of America’s glamorous Roaring Twenties through a lens pointed at America’s backyard. Though she used her images as teaching tools, Johnston understood their potential to tell a story of an ephemeral moment in history.

The slides range from grand boulevards of hedges and manicured blooms to yards bursting with wildflowers. Depending on the tastes of the colorists, glass lantern slides could be painted as meticulous replications of the scene or fantastical departures, or as Museum Specialist at the Archives Kelly Crawford says, “sometimes the roses are red and sometimes the roses are blue.” Projected on a screen, the painted slides offered a rich way to view the images for lectures while the black and white negatives could be easily reproduced for brochures.

Borrman’s critical role in identifying the Johnston’s images in the collections builds more narrative to the garden photographer’s story. After Sam Watters helped research and organize the Library of Congress’ 1,100 images, Borrman was able to use his research to pair hand-colored slides from the Archives with their black and white negative counterparts in the Library of Congress’ extensive collection which includes 20,000 prints and 3,700 glass and film negatives from Johnston.

“It’s very cool to be able to contextualize things in that way,” says Borrman, “because we have all of these random garden images from her but to see, ‘Oh, I know this was likely from her ‘Gardens of the West’ lecture series and this one is from ‘Tales Old Houses Tell.’”

Johnston’s interest in recreating an experience, whether it be in the luscious hand painting that accompanied the glass lantern slides or the narrative that guided each lecture, led her into other media. Borrman explains when Johnston went out West, “There were two things she was interested in in California; one was to make films of gardens, moving through a garden space but she never found the right contacts to do that.” And the other, was to make art from movie stills. She even had her own logo ready to go, but that, too was never to be.

Instead, Johnston used her contacts to partner with Carnegie and the Library of Congress to document the great architecture of the South. Like her work photographing garden estates, Johnston’s time in the South helped capture architectural styles many felt were facing extinction, particularly after the Great Depression.

Many of the images in the Archives come from that period. Borrman says they are particularly incredible because they include, not just elaborate homes, “but also vernacular architecture, gardens and landscape architecture.” Borrman has found images of churches, barns and other such structures.

Borrman says Johnston’s subject matter often revealed class tensions within America, a legacy likely far from the minds of garden lecture audiences. Movements such as City Beautiful and historical preservationism could reflect a proprietary sense of cultural ownership that those in power could impose on the urban landscape. What should be saved and what should be demolished were decisions few could participate in and Johnston’s work played a role in these conversations.

She helped spread the gospel of beautiful spaces from the wealthiest corners of the country. But her work has a doubleness.

Within art history, Borrman says, Johnston’s most prominent legacy is work she did prior to her garden photography. Having worked as a photojournalist, Johnston had a series of pieces from Washington, D.C. public schools of students engaged in classroom activities as well as the Hampton Institute in Virginia, where Booker T. Washington attended school. Borrman says these images have long been critiqued as racist studies.

“And certainly there are problems with those photographs but there are other stories in there, too,” says Borrman. For example, Borrman has been connecting the many images of children learning in nature and about nature from the series with her later work in garden photography and the broader movement of experimental learning. Another fraught social movement, experimental learning tried to place students in contact with nature. Seen as a solution to the ills of urban life, it was a facet of a collection of Progressive ideals that sought to civilize and improve the lives of the urban poor.

Years later, working for the New York City Garden Club, Johnston participated in an exhibition of city gardens. ”There’s some strangeness to that exhibit, too,” says Borrman. One of the photos on display was Johnston’s famous image of a janitor’s basement apartment entryway, overflowing with greenery. The man was honored at the exhibit as part of the club’s effort to encourage even those with few resources to craft window box gardens. “He was awarded this prize at the very same exhibit that someone who bought tenement buildings at Turtle Bay and recreated a backyard space and created this beautiful garden was also given a prize,” says Borrman. “So someone that had kicked out these poor people of their homes was awarded a prize in the same space as this janitor.”

Beautification projects routinely come back into fashion, says Crawford, citing Lady Bird Johnson’s highway efforts. The tensions prove perennial as well. Neighborhood improvements come with the specter of gentrification. The impeccable beauty of Johnston’s glass lantern slide operates on all these levels.

“There’s something that I love about her photographs that speak to these manipulated spaces and look so delicately constructed,” says Borrman.

For more on Frances Benjamin Johnston, we recommend the new book Gardens for a Beautiful America by Sam Watters.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Leah-Binkovitz-240.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Leah-Binkovitz-240.jpg)