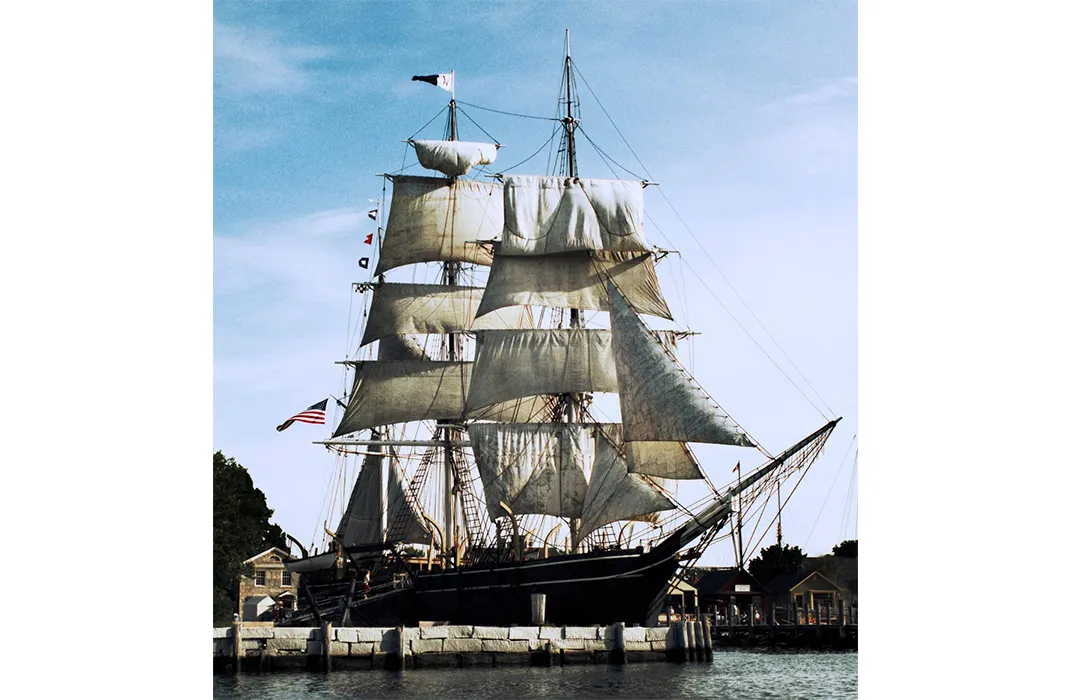

For the First Time in 93 Years, a 19th-Century Whaling Ship Sets Sail

Built in 1841, the Charles W. Morgan is plying the waters off New England this summer

In November 1941, a very tired and dilapidated wooden whaling ship, the Charles W. Morgan,was towed by a Coast Guard cutter up the Mystic River in Connecticut to the Mystic Seaport Museum. There, she rested on a bed of sand and gravel. Built and launched at the Hillman brothers’ shipyard in nearby New Bedford, Massachusetts, in 1841, the Morgan had sailed to all the corners of the globe in her hunt for the increasingly over-hunted whale; by the time she completed her 37th and final voyage in 1921, she had brought back 54,483 barrels of whale oil, earning $1.4 million.

Astonishingly, although the Morgan had been built to last just 25 years, she was already a century old when she was towed into the Mystic Seaport Museum. She was, in whaler’s parlance, a “lucky ship.” (Even though the ship’s name is masculine—in this case, the name of the principal owner—by nautical convention, the ship still remains a “she.”)

The Morgan’s new museum home, founded in 1929, was still inventing itself; the staff began to notice that a lot of people were stopping by, hoping to see this relic of the great age of New England whaling. Thus began the second life for the old girl, as staff and volunteers began to study and restore her, bringing her back to life.

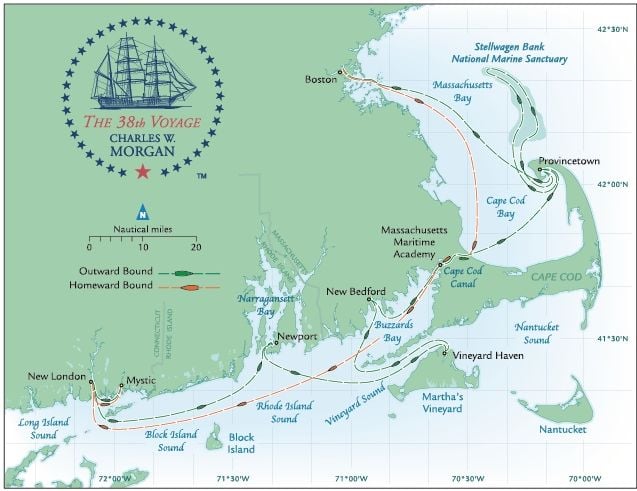

And now, the Charles W. Morgan—the last remaining wooden whaling ship in existence, and the most treasured possession of the Mystic Seaport Museum, a Smithsonian Affiliate—will set out on her 38th voyage. The ship has just undergone an extensive five-year renovation and, on May 17, she will be towed down the Mystic River (her first time below the Mystic River Bascule Bridge since she arrived in 1941) and over to New London, where she will remain for a month for the final preparations for this, her first modern voyage. Then she will cruise up the New England coast, paying visits to other historic ports. Her itinerary includes New Bedford, her homeport for 60 years, with its fine whaling museum; and Boston, where she will be berthed alongside the USS Constitution, the only American ship older than the Morgan. The port visits will include tours of the ship, whaleboat races, dockside exhibits—a full-out immersion in the history of whaling.

There will also be another very important stop—a reunion of sorts. Mooring offshore near Provincetown, the Morgan will make several day sails to Stellwagen Bank National Marine Sanctuary, which is a center for whale watching in New England. But it certainly wasn’t at the time of the Morgan; the sperm whales that had made Nantucket the whaling capital of the world before the rise of New Bedford had long since been hunted to near-oblivion in those waters. One whaling ground after another throughout the world was depleted, furnishing endless supplies of whale oil to lubricate the machines of the Industrial Revolution and to light people’s houses—a wild ride that ended only with the discovery of petroleum in Titusville, Pennsylvania, in 1859. But today, with the wisdom of hindsight, we can see the damage. So, on this 38th voyage, the Morgan will carry knowledge about protecting the whales, not casks filled with their oil.

“The idea that we might get the ship out to Stellwagen Bank and she might be surrounded by whales—that would be amazing,” says Mary K. Bercaw Edwards, who will crew on the Morgan during that leg of the 38th voyage.

A licensed captain, Edwards is the foreman of the museum’s demonstration squad, which sets the Morgan’s sails and mans the lookout hoops for museum visitors; she is also a professor at the University of Connecticut, where she is a scholar of Herman Melville, author of Moby-Dick. “Melville had a sense of the majesty of the whale,” says Edwards. “Most of the time, the whalemen thought of the whale as. . .beasts and monsters. But, like other hunters, they had a sense of reverence for the creatures. And also, they knew far more about the animals than they’re usually credited with, because they had to understand them so that they could find them. . .but they were also practical; until petroleum was discovered, that was the only way to get oil.”

Typical of whalers of her time, the Morgan was a little over a hundred feet in length, very beamy, with three masts, davits on her sides carrying four 25-foot-long whaling boats (which were about a third the length of their enormous prey), huge firepits on deck called tryouts (which meant the blubber could be boiled down on-site and stored for years without spoiling in the casks that filled the hold), a crew of 35, and everything required to support such a huge and complicated endeavor. Sailors aboard the swift and sleek clippers of the time looked down upon whaling ships, calling them “tubs” with their crew of “blubber men,” but the whalemen on these ships got the job done. If the clippers were the greyhounds of the sea, the whalers were the bulldogs.

“She’s kind of tubby; she’s slow,” Edwards says of the Morgan. “But her purpose was to hold as much oil as possible, and to be able to handle a three- to five-year voyage; so her design works really well for that. The actual hunt and kill were not from the ship, that was the whaleboats, which were fast and maneuverable; so they didn’t need to have speed from the ship itself.”

We actually have a day-to-day account of life at sea aboard the Morgan. While still a teenager, New Bedford-born Nelson Cole Haley signed on as a harpooneer to the ship’s second voyage, which he wrote about years later in clear-eyed and often humorous detail. Leaving New Bedford in 1849 for this four-year-long, around-the-world trip, the Morgan sailed down around Africa and the southern tip of Australia to hunt for sperm whales in the Pacific waters north of New Zealand. Haley, or “Nelt” as his shipmates called him, would live a long and happy life, even though that voyage alone threw enough adventure at him to last a lifetime—hurricanes whose winds, he later wrote, made the rigging screech “worse than forty tomcats sending up on a still night their musical strains in concert;” an angry whale that attacked his whaleboat from below (looking down into the water from the bow of the whaleboat, he could see it coming up), demolishing the boat and sending Nelt into a high flip before landing in the churning water; and his own success at sinking a harpoon into the side of an unsuspecting, busily feeding whale “as big as a mountain.”

Then there was the close call with the native inhabitants of an atoll in the Central Pacific, who, intent on raiding the ship, paddled out in dozens of canoes as the becalmed Morgan floated haplessly toward a coral reef. Believe it or not, Haley tells us that, while waiting to see if the ship ended up on the reef, one of the high-ranking canoers actually stood up, turned around and mooned the ship; and, from the ship’s deck, the captain hit home with a shotgun blast, sending the cheeky offender into the drink! The chastened islander survived the indignity and was pulled aboard another canoe, and the ship just barely missed the reef, but many whaling ships were not so fortunate.

Haley, whose account has been published by the Mystic Seaport Museum under the title of Whale Hunt, describes the Morgan’s adventures as only an eyewitness can do. But there are all kinds of other resources devoted to the ship, including a monograph, The Charles W. Morgan, available from the museum; and a new film directed by Connecticut filmmaker Bailey Pryor, which is slated for airing on PBS stations around the country. Plus, the museum’s website is loaded with information about the coming 38th Voyage, the history of the ship, and—with terrific journal entries and photographs—the details of the Morgan's recent restoration.

The five-year restoration, which was carried out at the museum under the supervision of shipyard director Quentin Snediker, required more than 50,000 board feet of live oak and other woods for framing, planking and other structural elements. On the day the final plank (the “shutter plank”) was installed in the ship’s hull, a ceremony was held. “The shutter plank…marks the end of the single largest aspect of the project,” said Snediker. There would, he added, still be miles of caulking and puttying, and thousands of square feet of painting to do on the Morgan, but “from here on out, she’s whole.”

One thing that has been “whole,” throughout all these years, is the Morgan’s keel. “The keel is all original,” Edwards says. “That’s because it was in the salt water. And then the lower frames…we had to replace some of those, but fewer than we expected because the salt water is such a great preservative. The upper part, which has been exposed to fresh water, has been replaced several times, but the lower part is original.” When the planks deep inside the hull were removed, the hull’s frames were revealed for the first time since 1841. “That was my favorite part of the restoration,” Edwards says; “to go into the bottom of the ship and sort of sit there.”

The cost of building the Morgan in 1841 was $27,000, and once she was fully equipped, $52,786. The cost of the restoration at Mystic Seaport Museum was $7.5 million. But more than 20 million visitors to the museum have toured the Morgan, and now, because of this restoration, their children and grandchildren will also be able to walk her decks. “When the Charles W. Morgan was built, they were expecting the ship to live 20 to 25 years,” Edwards says. “We’re trying to make the ship live forever…one hundred and seventy years more.”

Update 5/17/14: This article was updated to include new information about the original cost of the ship and the restoration.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/bond.jpg)