At American History, Meet the Composer of the Spanish Language National Anthem

From the Amazon River Basin to Madison Avenue, the woman behind the Spanish translation of the Star-Spangled Banner united the Americas

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/20120927123040Arias_Thumbnail.png)

In 1945, the Department of State held a competition to create an official Spanish translation of the National Anthem “The Star-Spangled Banner” using the original score. Because Spanish translations tend to be at least one and a half times the length of English originals, it was a daunting task. Other translations had already been done, according to Marvette Perez, curator of Latino History at the American History Museum, but none had successfully remained faithful to the anthem’s music and composition.

Enter Clotilde Arias, a Peruvian immigrant, composer and copywriter, who was dedicated to the Pan-American movement. Her winning entry became the official U.S. Spanish translation, but the work represented just a microcosm of a vast lifetime output from a woman, born in the Amazon River Basin who later not only became successful writing jingles and slogans on Madison Avenue but also became a musician, a journalist, an activist and an educator. Now largely forgotten, her incredible journey is the subject of a new American History Museum exhibit, “Not Lost in Translation: The Life of Clotilde Arias.”

As World War II raged across its various fronts, a small army was mobilizing in the States. Armed with typewriters, bells and whistles, and fluency in both English and Spanish, the soldiers were musicians, artists and copywriters. In service to President Roosevelt’s “Good Neighbor Policy,” they were called to strengthen the ties between the United States and Latin America. Through performances and cross-cultural marketing, they revealed and supported the web of connections across the hemisphere.

Though the goodwill suffered after the end of the war, Arias remained dedicated to a Pan-American vision until her death in 1959.

Arias was born in Iquitos, Peru, “the only big city in the world that you cannot reach by road, only by plane or boat, to this day,” explains curator Marvette Perez. Because of a rubber boom, the Amazon River Basin city was suddenly home to barons and mansions in the late 19th century. Caught somewhere between the wealthy industry titans and the enslaved indigenous peoples, her family led a middle class life, moving briefly to Barbados where she received a British education and learned English before moving back to Iquitos.

“It’s a very complicated place that she comes from and it’s very interesting,” says Perez. “I think this had a lot to do with what she became later.”

Though she wrote for the local newspaper, Arias wanted to be a composer. In 1923 at the age of 22, she moved to New York City to study music. Living in Brooklyn, Arias began her bilingual life in earnest, writing jingles in both English and Spanish.

Photographs, digital recordings and postcards tell the story of her journey to Madison Avenue, working among the same characters that now populate AMC’s Mad Men and writing advertising slogans for Pan Am, Campbell’s Soup and Alka-Seltzer. A vivacious woman, Arias built a network of friends that included Harlem Renaissance artists, advertising giants and high-society Du Pont family members.

Contemplating its post-war position in the world, America had both the swagger of the hard-drinking businessman and the optimistic vision that helped found the United Nations. Arias was able to combine both into a dream of Pan-American unity.

In the exhibit, her diary is open to the page expressing her belief in a common humanity. Perez says, “She converted to Bahai at some point in her life because the Bahai believed in the unity of people and she felt very close to that idea.”

Arias captured all of her triumphs in a scrapbook, on display. “I always find scrapbooks so interesting because they’re people’s memories,” says Perez, “You see what’s important to them.” Examining the pages of Arias’ scrapbook, Perez says she sees a woman tremendously proud of her work. In the official records, Arias lives on as the first person able to keep both meter and meaning, as Perez says, intact in a translation of the National Anthem. But in her own records, her vision of herself and of the world offers so much more.

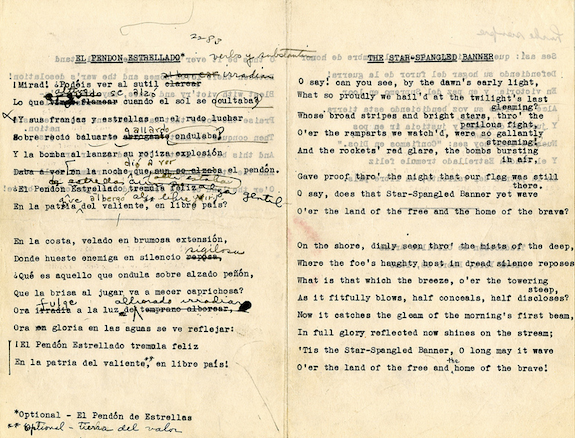

“Not Lost in Translation: The Life of Clotilde Arias” includes the original music manuscript of “El Pendón Estrellado,” Arias’ translation of the “Star-Spangled Banner.” The exhibition is on view from September 27, 2012 through April 28, 2013, and includes a 2 P.M. performance this Saturday, September 29 in the museum’s Flag Hall by the chamber chorus Coral Cantigas. The group, specializing in the music of Latin America, will bring to life Arias’ 1945 translation and will also feature her best-known composition “Huiracocha.” A repeat performance will follow at 3 p.m. and at 4 p.m.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Leah-Binkovitz-240.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Leah-Binkovitz-240.jpg)