At American Art: A New Look on How Artists Recorded the Civil War

A groundbreaking exhibit presents the Civil War through the eyes of artists uncertain of the conflict’s outcome, shedding fresh light on the events

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/20121116040035Homer_Prisoners_From_The_Front-thumb.jpg)

Its battles, its generals, its lasting political implications are all fairly familiar territory to most, but the Civil War’s art is another story altogether. In the midst of a sesquicentennial anniversary, the country turns again to that defining moment with exhibitions, books and movies, including the current blockbuster film Lincoln by director Steven Spielberg.

But it took the dogged determination of curator Eleanor Jones Harvey to bring together a unique exhibit full of original scholarship that tracks how the war was portrayed in art before, during and after and how that war changed forever the very categories of landscape and genre paintings or scenes of everyday life, as well as photography in America. The American Art Museum’s exhibition “The Civil War and American Art” shows how American artists and the broader public wrestled with a war that fractured a country’s young identity.

According to Harvey, it has long been assumed that the great landscape artists “took a pass” on the Civil War, seeking not to sully their pristine paintings with the problems of the war. But, she says, the precise opposite occurred.

Her first clue came while reading the journals of two Texas soldiers who described the scene of a bloody Confederate victory as a metaphorical landscape of wildflowers, covered in red. From there, she says, similar allusions to weather and landscape were easy to spot in newspapers, poems, sermons and songs. Talk of a coming storm filled the country’s pews and pamphlets in the years leading up to the war.

A stunning meteor event in 1860 inspired Walt Whitman’s “Year of Meteors,” which referenced both John Brown’s raid and Lincoln’s presidency. The public could not help but read the skies for signs of war. Harvey says some even worried that the meteor, which passed as a procession over Manhattan, might be a new military technology from the South. She adds that when viewers first saw the dark foreboding skies of Frederic Edwin Church’s Meteor of 1860, the anxiety over the pending war was writ large.

Storms, celestial events and even volcanic eruptions mixed with religious metaphor informed the conversation of the day. “This imagery found its way into landscape painting in a manner that was immediately recognizable to most viewers,” writes Harvey in a recent article. “The most powerful of these works of art were charged with metaphor and layered complexity that elevated them to the American equivalent of grand manner history paintings.”

Among the 75 works in the exhibit–57 paintings and 18 vintage photographs–grand depictions of battles in the history painting tradition are noticeably absent. “There’s no market for pictures of Americans killing each other,” says Harvey. Instead, artists used landscape paintings like Sanford Gifford’s A Coming Storm and genre paintings like Eastman Johnson’s Negro Life at the South to come to terms with hardships and heart aches of four years of war.

By drawing on pieces made in the midst of conflict–indeed, many of the artists represented in the show spent time at the battlefront–Harvey says she wanted to address the question “What do you paint when you don’t know how the war is going?” In other words, what future did America think was waiting at the end of the war.

While the exhibit’s epic landscapes deal in metaphors, the genre paintings look more directly at the shifting social hierarchy as people once enslaved now negotiated for a lasting freedom in an unyielding society. Johnson’s A Ride for Liberty–The Fugitive Slaves, March 2, 1862, for example, depicts a young family presumably fleeing to freedom. But, Harvey points out, Johnson painted this while traveling with Union General George McClellan who chose to turn back runaway slaves. “We want to read these as benign images,” says Harvey, but the reality on the ground was anything but.

Winslow Homer also spoke to the uncertainties many faced after the war. In his arresting genre painting, A Visit from the Old Mistress, the artist captures a stare-down between a former slave owner and the women who were once considered her property. Harvey says she’s watched visitors to the exhibit head in for a closer look and get caught in the depicted standoff, stepping back uncomfortably. There is no love shared between the women, no hope for the now-dead myth that perhaps slaves were, in some way, part of the families they served.

But for the newly freed and others, the fields were still waiting. The Cotton Pickers and The Veteran in a New Field, also by Homer, show the back-breaking labor that still characterized life after the war. The solitary veteran, for example, has his back to us, his feet buried. “All he can do is keep scything things down,” says Harvey.

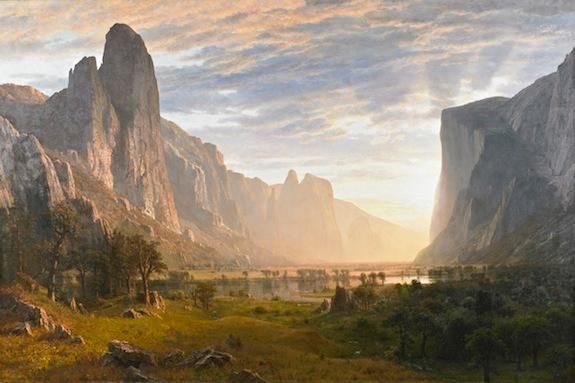

A final gallery of landscapes returns visitors to the metaphors presented earlier. This time, artists take up the idea of America as a new Eden and the attempt to once again find a redemptive narrative in the land. Closing with Albert Bierstadt’s Looking Down Yosemite Valley, California, the exhibit ends not in the North or South, but gazing West. The failure of Reconstruction was yet to come. But in the West, America hoped it had found another chance at Paradise.

Harvey’s accomplishment has, in a single exhibit, untied the Civil War from the straight jacket of a rehearsed and certain narrative and returned us to the uncertain precipice of its promise.

“The Civil War and American Art” opens November 16 and runs through April 28, 2013 before heading to the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York City.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Leah-Binkovitz-240.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Leah-Binkovitz-240.jpg)