Meet the Muses Who Inspired Some of the World’s Most Iconic Artworks

A new book examines the lives of muses across history and the role they played in shaping treasured works like “The Kiss” and “Ophelia”

:focal(1750x1050:1751x1051)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/0c/f5/0cf5fcb6-cf4b-46c1-84a3-ddd9bfdf5904/gettyimages-154384638.jpg)

The most iconic muses in art history implore us to ask more questions. Who were they? What were their lives like? How did they know the artists who painted them? But their almost inscrutable nature, the way their persona is both splashed across the canvas and hidden from it, defies our curiosity—and is precisely what engenders so much fascination. Just think of the Mona Lisa’s half-smile, so permeated in the public consciousness that a mere mention brings it viscerally to mind.

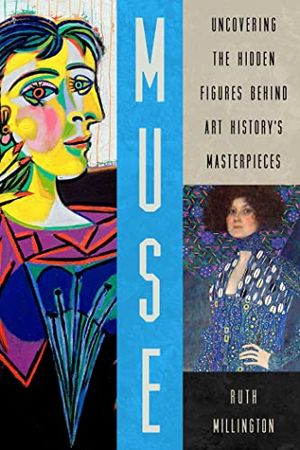

Discussions of muses usually center the artist first, with the painter as creator and the muse as sitter. But a new book argues that we’ve had it all wrong. In Muse: Uncovering the Hidden Figures Behind Art History’s Masterpieces, art historian and critic Ruth Millington explores the lives of a collection of muses, the role they played in art history and the legacy they left through their own lives. According to the Art Newspaper’s Gareth Harris and José da Silva, the 30 muses featured include an array of “unexpected and overlooked figures,” as well as better-known individuals.

Muse: Uncovering the Hidden Figures Behind Art History's Masterpieces

The fascinating true stories of 30 incredible muses—and their role in some of art history's most well-known masterpieces

Millington’s analysis examines the muses of famous painters like Diego Velázquez, Pablo Picasso and Gustav Klimt. In the first chapter, she analyzes Velázquez’s 1650 portrait of his then-enslaved assistant, Juan de Pareja, whom the artist would later release from bondage. (De Pareja went on to become an artist in his own right.) In another, the scholar looks at Picasso’s Weeping Woman, an anguished 1937 portrayal of his lover, photographer Dora Maar. Millington also explores the story of Klimt’s longtime friend Emilie Flöge, a fashion designer whose clothes featured in the painter’s work and who may have been depicted in The Kiss (1907–08).

Muse pushes back on the perception of muses as submissive, a blank canvas rather than one bursting with ideas. She compares our contemporary idea of the muse to the ancient Greek muses, nine goddesses who represented the arts, rhetoric, tragedy, dance and astronomy, among other disciplines. Epic poems like Hesiod’s Theogony, the Odyssey and the Iliad all begin with some sort of invocation to a goddess or muse.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/48/0b/480b5b9c-0526-46f7-8a62-f86ea783a155/dp-14286-001.jpeg)

“At their ancient origin, the muses were far from passive subjects for an artist to paint or write about,” Millington explains. “Instead, they were agents of divine inspiration. The artist-muse relationship was one that was revered, and poets, at their mercy, paid homage to those divinities.”

Millington’s own definition of muse is broad and unconventional, encompassing not just the person behind the portrait but the celebrity crafting a specific image, the film star who plays a thousand roles in one photo shoot and the artist whose favorite subject is herself. These categorizations expand our very idea of what it means to be a muse.

The book is divided into seven chapters looking at the muse’s every facet: as an artist in their own right, as the self, as a family member, as a lover, as a performer, as a representative of an artistic movement and as a social message. Millington asks whether muses are simply taken advantage of or if they are inspiring forces with real agency. The answer, of course, is murky and lies somewhere in the middle.

When it comes to Picasso’s relationship with Maar, for example, the two were in many ways symbiotic, Millington tells Atlas Obscura’s Sarah Durn. Picasso’s style may have informed Maar’s own work, but she introduced him to photography and “to her ultra-left-wing politics at a time when it was really rare for women to be a member of such parties.” In fact, her daring political stance likely led the artist to paint Guernica, a sprawling black-and-white painting depicting the 1937 German bombing of a Basque town during the Spanish Civil War. The attack destroyed about 70 percent of Guernica and killed or injured 1,600 people—roughly one-third of the town’s total population.

To Millington, Picasso used the word “muse” as something to hide behind, a way to obscure the real story.

“I feel like Picasso and other 20th-century artists played into these myths of the muse,” the author tells Atlas Obscura. “They were presenting this idea that to be a great artist, you could and maybe even had to be in possession of a muse. They also frame the muse in this power imbalance. ‘Artist’ is active. ‘Muse’ is passive.”

Even Maar later called all of Picasso’s portraits of her “lies,” claiming that “not one” represented her.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/f2/ce/f2ce10a7-debc-4089-820b-8439a3fec7fa/1280px-john_everett_millais_-_ophelia_-_google_art_project.jpeg)

Other muses, like Elizabeth Siddal, who graced John Everett Millais’ Ophelia (1851–52) as Hamlet’s ill-fated lover, are commonly depicted as tragic figures. The process of sitting for the painting proved quite arduous; Siddall lay in a bath full of water, with oil lamps underneath to keep the water warm, for hours on end.

“On one occasion, the lamps went out and Millais was so engrossed by his painting that he didn’t even notice,” notes Tate Britain, where the painting resides. “During her time posing for the painting, Elizabeth got very cold and became quite ill.” Her father paid for a private doctor but later ordered Millais to cover the medical bills in full.

But even Siddal is not all her story makes her out to be. Indeed, writes Millington, the model was paid—and paid well—for her work.

“She modeled part-time alongside her job in the hat shop, but over time, she turned musedom into a profitable career on its own,” Millington adds.

Other muses reflect a larger point. Chris Ofili’s No Woman, No Cry (1998) portrays Doreen Lawrence, whose teenage son was stabbed to death in a racist attack in 1993. The portrait shows Lawrence with light blue tears flowing from her face. Inside each tear, Ofili placed a collaged photograph of her son Stephen.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/c0/65/c0655dd0-9107-4b7d-939a-43d056fa66d3/800px-official_portrait_of_baroness_lawrence_of_clarendon_crop_2_2019.jpeg)

“The painting can be read as a modern day pietà,” writes Millington. “Echoing the grief-stricken figure of Mary, Ofili’s figure is treated with tenderness and intensity, invoking compassion in viewers for both Doreen Lawrence and all mourning mothers.”

Modern muses, Millington suggests, are as artistic as the artists who portray them. As photographer Tim Walker told the author, a portrait of a muse—versus a model—is like “a handshake, the embrace, the agreement where we meet halfway along a collaborative path.”

“In today’s post-feminist world, women continue to consciously reclaim the role of an active, authoritative muse. Grace Jones, Beyoncé Knowles, Tilda Swinton—all of these women are formidable agents who choose to enter into an artist-muse relationship on their own terms,” Millington writes. “Modern muses such as these play a defining part in determining the final image.”

A Note to our Readers

Smithsonian magazine participates in affiliate link advertising programs. If you purchase an item through these links, we receive a commission.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/elizabeth2.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/elizabeth2.png)