Happy Birthday to the Modern Pencil

The patent for this supremely convenient invention didn’t last long

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/c5/68/c568b331-7964-44a6-b33f-6ae4971b83ec/istock-136995804.jpg)

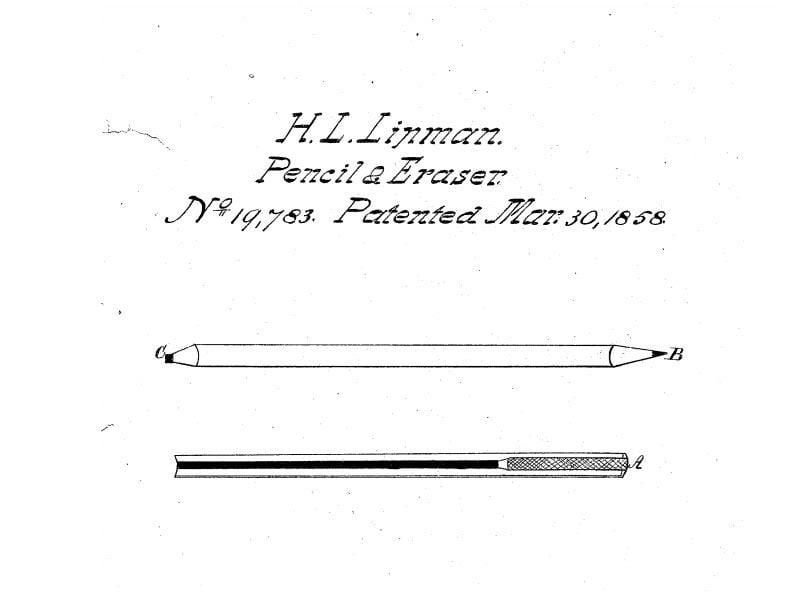

On this day in 1868, Philadelphia stationery store owner H.L. Lipman patented something that seems incredibly obvious in hindsight: a regular pencil, with an eraser on the end.

Although Lipman is credited with this innovation, his pencil with eraser looked a little different than its modern descendant. Rather than being glued onto the end, Lipman envisioned a pencil with a chunk of rubber eraser in the core that could be accessed by sharpening it, the same way you would a pencil lead.

Graphite pencils had been around since the 1500s, writes David Green for Haaretz. But until the 1770s, the preferred tool used to erase pencil marks was balled-up bread.

Lipman’s name hasn’t gone down in history, maybe because he didn’t manage to hold on to his patent. After gaining it, he sold it to Joseph Reckendorfer in 1862, writes Green, for about $2 million in today’s money. Reckendorfer also didn't get much use out of the patent. He took another company to court over their use of his patent, only for it to be invalidated by the court’s decision, which stated that Lipman merely combined two existing things, but didn’t really produce something new.

“It may be more convenient to turn over the different ends of the same stick than to lay down one stick and take up another,” the decision noted. “This, however, is not invention within the patent law.”

Over his career, though, Lipman also made a number of contributions to the 19th-century office, Green writes:

Lipman was also America’s first envelope manufacturer, and it was he who had the idea of adding adhesive to the back flap, so as to make sealing easier. He devised a methods for binding papers with an eyelet that preceded the stapler by two decades. And Lipman was the first to produce and sell blank postcards in the United States, in 1873.

He bought the patent for these postcards from another stationer, Green writes, but they came to bear his name, being called the “Lipman card.”

Pencils aren’t really a notable object, writes Henry Petroski in The Pencil: A History of Design and Circumstance, but they shape how people do their work. Unlike the pen, a more permanent writing instrument, the pencil doesn’t usually get sayings (it’s the pen that’s mightier than the sword, for example) or a lot of credit. But pencil is an essential creative medium, he writes, because it can be erased—as everyone from architects to artists can tell you.

“Ink is the cosmetic that ideas will wear when they go out in public,” he writes. “Graphite is their dirty truth.”