Curators Are Preserving Graffiti Scrawled By WWI Conscientious Objectors

The cell walls at Richmond Castle are still covered in drawings and notes

In March 1916, Great Britain's Military Service Act went into effect, which conscripted all unmarried men between the ages of 18 and 41 into service in the First World War unless it would cause serious hardship for their dependents, they worked in a civilian job of national interest or they were ill. According to a release from English Heritage, Parliament also grudgingly included a conscientious objector clause in the bill, allowing men who opposed the war to join a Non-Combatant Corp.

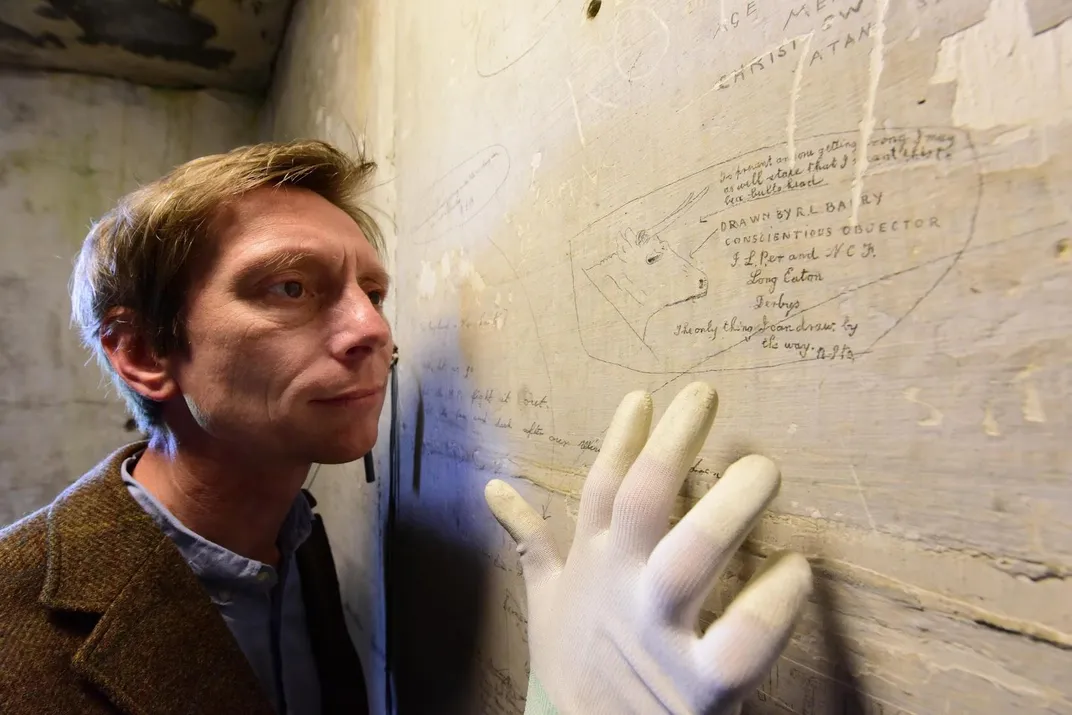

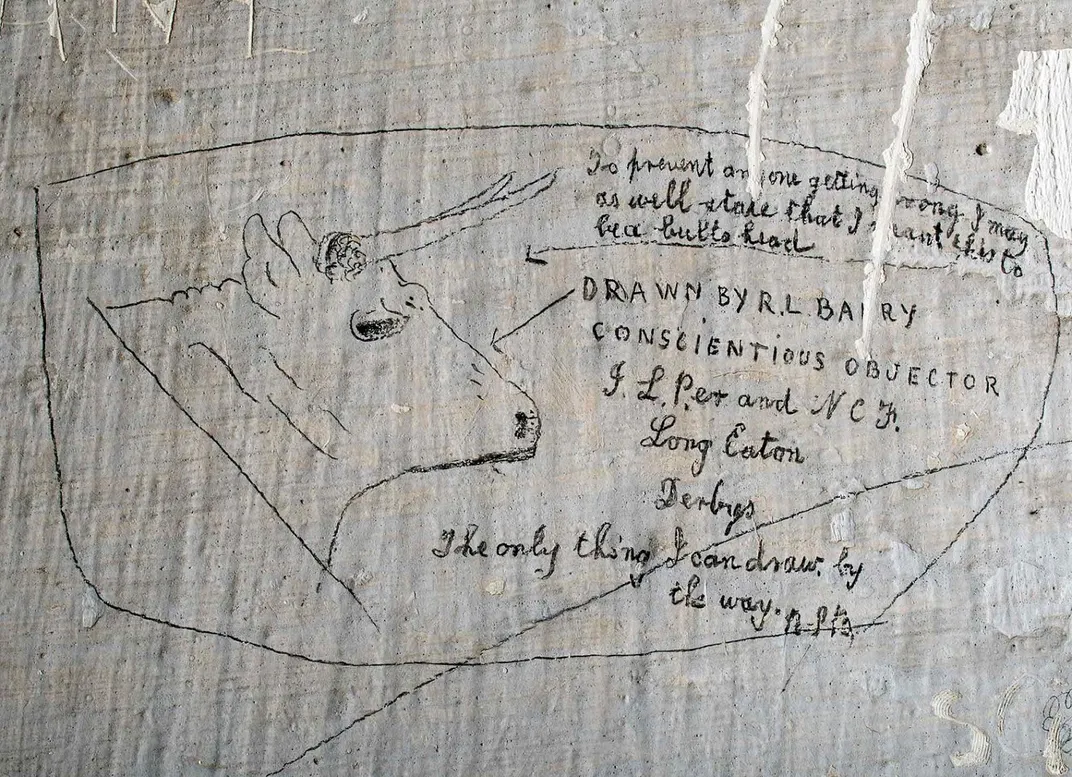

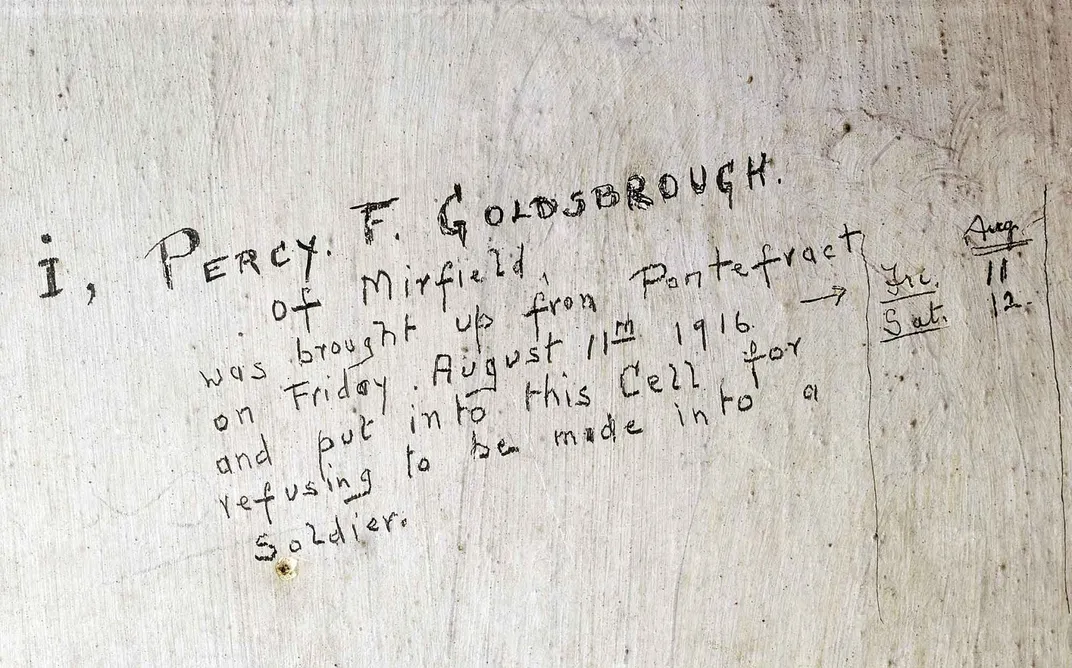

It was a rough road for objectors, English Heritage points out. They often had difficulty finding jobs after the war and were shunned by family and their communities. In the Midlands of England, conscientious objectors reported to the 2nd Northern Company of the Non-Combatant Corps in Richmond, Yorkshire for duty. But some men, called absolutist objectors, refused to perform even non-combat service, and faced prison and military discipline. Many of them ended up in cells at Richmond Castle, where they wrote messages and drew pictures on the walls of the cold, damp cells using pencils. Now English Heritage has started a project to preserve some of the roughly 5,000 drawings, hymns and thoughts scrawled on the crumbling cell walls that now date back 100 years.

“It is absolutely astonishing that so many of these have survived for a century, but they are now as fragile as cobwebs,” Kevin Booth, the conservator leading the project tells Maev Kennedy at The Guardian. “This is the last chance to save, if we can, or at least record them.”

The most famous absolutist objectors are known as the Richmond 16, a group of socialists, Jehovah’s Witnesses, Quakers and men of other religious affiliations who refused military service or non-combat service, and were sent to cells in Richmond Castle.

On May 29, 1916, The Richmond 16 were forcibly shipped to the front in Boulogne, France. They were given a choice: either join the Non-Combatant Corp or face court martial and execution, according to an article by Megan Leyland at English Heritage. One of the men joined the Corp, but the other 15 were steadfast. Along with 19 other COs from other parts of Britain, they were initially condemned to death, though the sentences were later commuted to 10 years of hard labor.

Richmond Castle was also used as a lockup for misbehaving soldiers during World War II, and Booth tells Kennedy that many of them added or commented on the graffiti made by the previous generation. “The Richmond 16 has been the only story, but there is so much more in these walls,” Booth says.

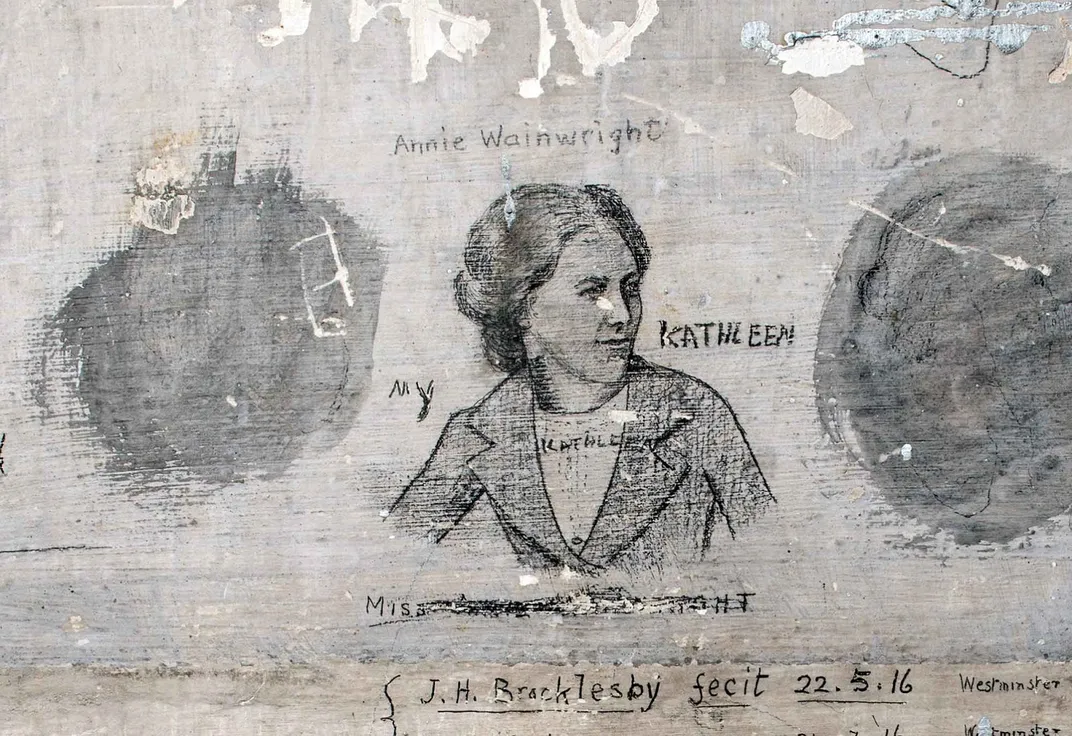

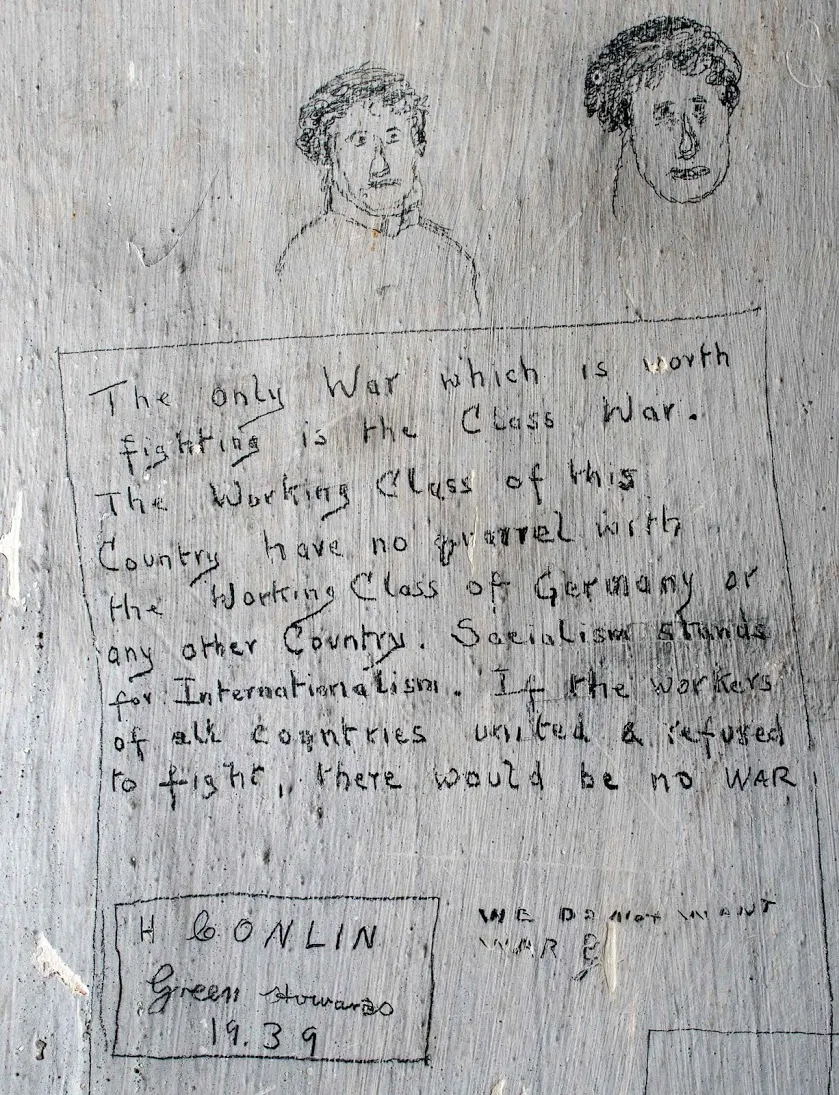

Volunteers are being recruited to record the graffiti and attempt to identify its authors. Kennedy points out that there are few crude drawings or dirty jokes on the walls. Instead, there are hymns, Bible verses, political statments, intricate drawings of wives and mothers and scenes from World War I.

“The only War which is worth fighting is the Class War. The Working Class of this Country have no quarrel with the Working Class of Germany or any other Country. Socialism stands for Internationalism. If the workers of all countries united and refused to fight, there would be no war” writes one prisoner.

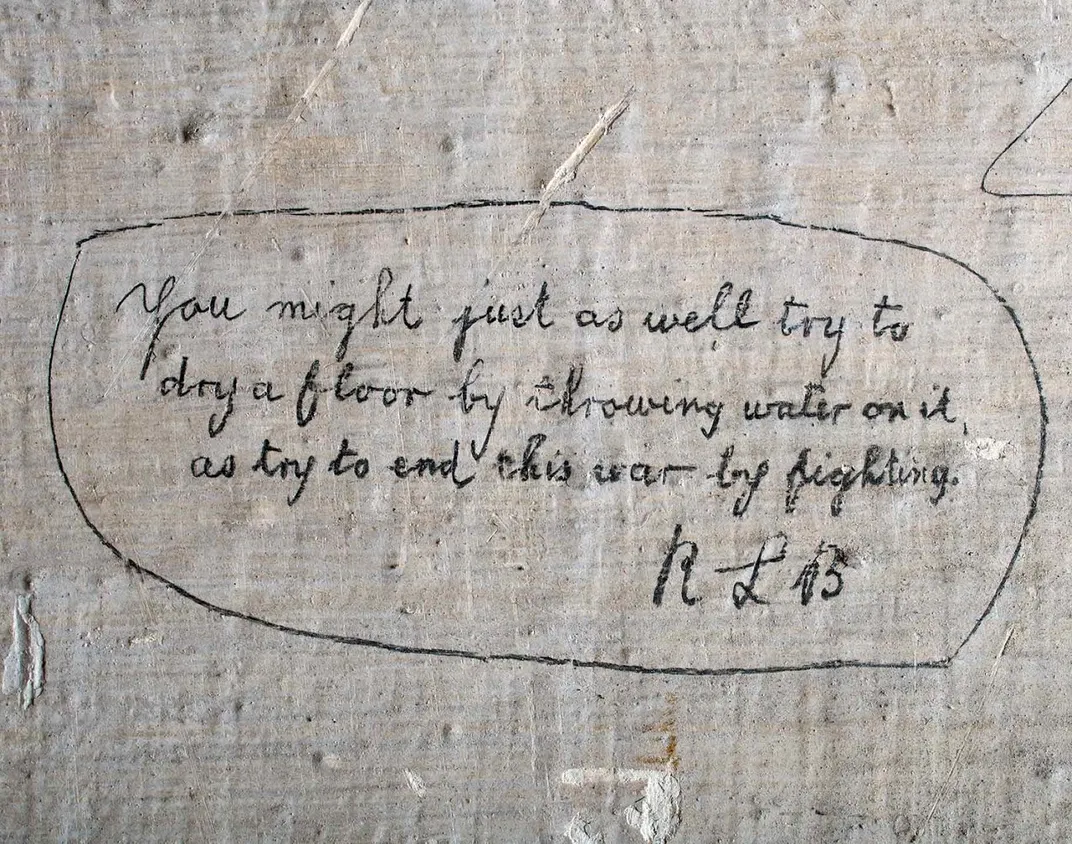

Richard Lewis Barry, a lace factory worker from Derbyshire wrote in 1916, “You might as well try to dry a floor by throwing water on it, as try to end this war by fighting.”

According to The History Blog, English Heritage will spend about half a million dollars to preserve the cell walls between now and 2018 before opening the area to the public.