Unprecedented Carved Skulls Discovered at a Stone Age Temple in Turkey

Three carved skull fragments from Gobekli Tepe offer tantalizing hints about the lives of Neolithic people

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/f9/73/f9735919-9583-4698-8bee-e2ad489de4d0/skull_cult_2.jpg)

Archeologists at a Stone Age temple in Turkey called Göbekli Tepe have discovered something straight out of Indiana Jones: carved skulls. The deeply chiseled human craniums are the first of their kind in the region. Taken together with statues and carvings depicting headless people and skulls being carried, researchers suggest the ancient people of Göbekli Tepe may have belonged to a "skull cult," reports Andrew Curry at Science.

When researchers first began excavations at the 12,000-year-old temple, they expected to find human burials. Instead, they unearthed thousands of animal bones as well as 700 fragments of human bone, more than half of which came from skulls, Curry reports. But only three fragments were modified with incisions.

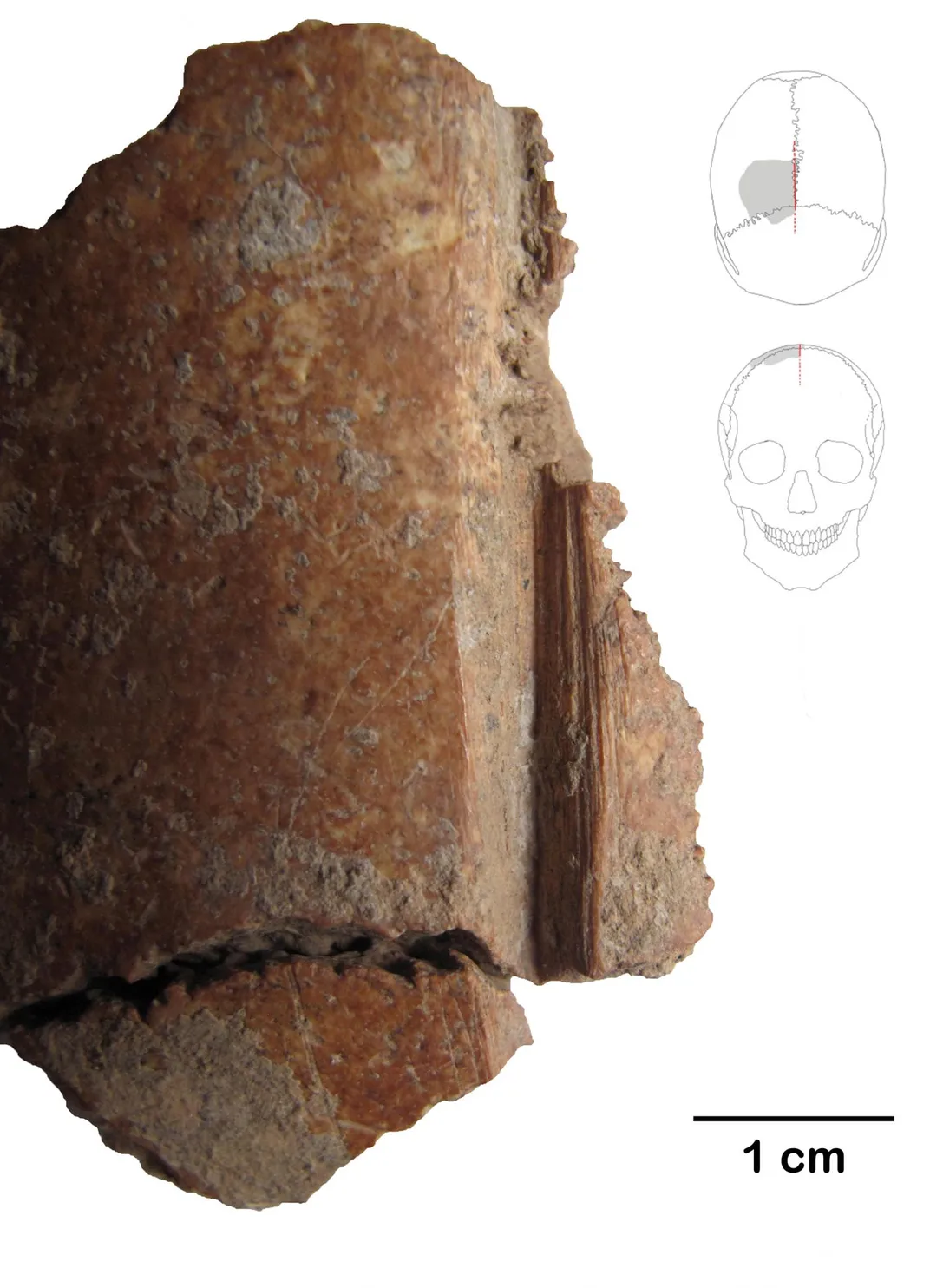

According to a press release, one of the skulls had a hole drilled through it and contained remnants of red ochre, a pigment used for millennia in cave paintings and religious rituals. Using the latest microscopy techniques, the researchers from the German Archeological Institute ruled out the possibility that the marks were made by animals gnawing the bones, or by other natural processes. Instead, they were made with flint tools not long after the individuals had died. Other small marks show the skulls were defleshed before carving. The research was published Wednesday in Science Advances.

Artwork recovered at the site also shows an interest in decapitated heads: One statue was beheaded, perhaps intentionally, and another called “The Gift Bearer” depicts someone holding a human head.

The researchers are uncertain what the skulls were used for. They speculate the bones could have been hung on sticks or cords to scare enemies, or decorated for ancestor worship. Lead author Julia Gresky tells Ian Sample at The Guardian the hole in one fragment would have allowed the skull to hang level if it was strung on a cord, and the grooves would help prevent the lower jaw from falling off. “It allows you to suspend [the skull] somewhere as a complete object,” she says.

While the markings are unlike any the researchers have come across before, the obsession with skulls is not. “Skull cults are not uncommon in Anatolia,” Gresky tells Shaena Montanari at National Geographic. Remains from other sites in the region suggest people exhumed the skulls of their dead and even reconstructed their faces using plaster.

The other mystery at Göbekli is that the carvings only appear on three skulls, even though many skull fragments have been unearthed there. It’s hard to imagine why these three particular individuals were singled out. Some researchers have expressed skepticism that the limited evidence offers proof of rituals or decoration. "This is thousands of years before writing so you can't really know. The marks do appear to be intentional, but what the intention was I can't say," archaeologist Michelle Bonogofsky told Curry.

While the skull cult is exciting, Göbekli Tepe has already upended what we know about Neolithic people. Researchers previously believed religion and complex society emerged after the development of agriculture. But Curry reports for Smithsonian Magazine that Göbekli and ritual sites like it show the timeline may be the other way around: hunter-gatherers may have flocked to the sites, requiring agriculture to support their large gatherings.