Watch a Tick Burrowing Into Skin in Microscopic Detail

Their highly specialized biting technique allows ticks to pierce skin with tiny harpoons and suck blood for days at a time

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/20131029070203tick-bite.jpg)

One of the freakiest parts of getting bitten by a tick is the insect arachnid’s incredible tenacity: If one successfully pierces your skin and you don’t pull it off, it can hang on for days at a time, all the while sucking your blood and swelling in size.

From video © Dania Richter

Despite plenty of research into ticks and the diseases they carry, though, scientists have never fully understood the mechanics by which the insects they use their mouths to penetrate skin and attach themselves so thoroughly. To address that, a group of German researchers recently used specialized microscopes and high-speed video cameras to capture a castor bean tick burrowing into a mouse’s bare skin in real time.

Their work, published today in Proceedings of the Royal Society B, produced all sorts of new revelations about the structure and function of the tick’s mouthparts. Perhaps the most harrowing part of the research, though, is the microscopic video they captured, shown at an accelerated speed above.

The team of scientists, led by Dania Richter of Charité Medical School in Berlin, conducted the work by placing five ticks on the ears of lab mice and letting them have their fill of blood. Unbeknownst to the ticks, though, they’d been caught on camera—and by analyzing the footage, along with detailed scanning electron microscope images of the ticks’ mouth appendages, the researchers found that the insects’ bites are really a highly specialized two-step process.

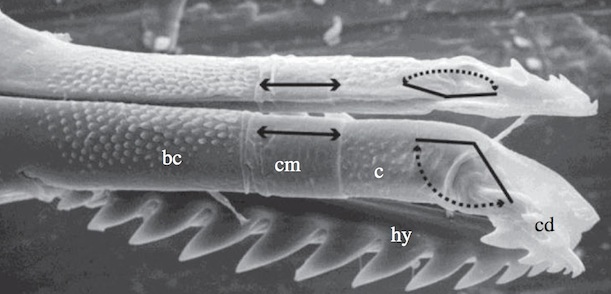

To begin, after the tick has climbed aboard a host animal, a pair of sharp structures called chelicerae, which are located at the end of its feeding appendage, alternate in poking downward. As they gradually dig, their barbed ends prevent them from slipping out, and the tick slowly and shallowly lodges itself in the skin, as seen in the first few seconds of the video.

A microscopic view of a tick’s feeding appendage, with the chelicerae on top (hinged tips labeled cd, telescoping portion labeled cm) and the hypostome on bottom (labeled hy). Image via Ritcher et. al.

After about 30 or so of these small digging movements, the tick switches to phase two (shown just after the video above zooms in). At this point, the insect simultaneously flexes both of the telescoping chelicerae, causing them to lengthen, and pushes them apart in what the researchers call “a breaststroke-like motion,” forming a V-shape.

A schematic of the tick feeding appendage’s “breaststroke-like motion,” which allows it to deeply penetrate the skin. From video © Dania Richter

With the tips of the chelicerae anchored in the skin, flexing them outward causes them to penetrate even deeper. When this occurs, the tick’s hypostome—a razor-sharp, even-more-heavily-barbed spear—plunges into the host’s skin and attaches firmly.

The tick’s not done, however: It repeats this same breaststroke five or six times in a row, pushing the hypostome deeper and deeper until it’s fully implanted. With the hypostome firmly in place, the tick begins drawing blood—sucking the fluid up to its mouth through a grooved channel that lies in between the chelicerae and hypostome—and if left interrupted, will continue until it’s sated days later.

This new understanding of how ticks accomplish this feat, the researchers say, could help us someday figure out how to prevent transmission of the most feared risk of a tick bite: Lyme disease. Scientists know that the disease is caused by several different species of bacteria that adhere to the inner lining of the tick’s gut and typically make the jump into a human’s bloodstream only after a full day of feeding. Knowing how ticks are able to attach themselves so stubbornly could eventually allow us to determine a means of thwarting their advances, before the Lyme-bearing bacteria have a chance to cross the species barrier.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/joseph-stromberg-240.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/joseph-stromberg-240.jpg)