These Simple Fixes Could Save Thousands of Birds a Year From Fishing Boats

Changes as basic as adding a colorful streamer to commercial longline fishing boats could save thousands of seabirds a year

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/67/f2/67f281c1-1744-4db4-b00f-a039c956ee74/longline_notext.png)

Fishing vessels on the high seas have often meant easy meals for seabirds foraging in their wake. But those fish can come with some deadly strings attached for birds that collide with their lines, nets and hooks.

Hundreds of thousands of seabirds are injured or killed each year due to ill-fated run-ins with fishing gear, according to organizations like BirdLife International, a group of conservation nonprofits that monitors seabird bycatch.

Bycatch includes any unwanted fish or other marine species caught during commercial fishing for another species. Some unwanted fish can still end up on a restaurant menu all the same.

But there’s no such option for the albatross, petrels and gulls that are among the most commonly by-caught birds—some of them critically endangered species. Much has been done to reduce their bycatch in the 15 years since the American Bird Conservancy published a scathing report about the impact of longline fishing on seabirds, “Sudden Death on the High Seas,” but an estimated 600,000 birds still fall prey to fishing vessels each year.

At the time of the report, 23 species of seabird were in danger of extinction because of longline fishing problems that “can be solved easily and inexpensively,” the report stated.

Since then, the industry and regulators have adopted mitigation methods to reduce the number of birds being unintentionally reeled in. An Agreement on the Conservation of Albatrosses and Petrels (ACAP) went into effect in 2004 with thirteen countries—including the United Kingdom, Peru, South Africa and Australia—committing to reduce seabird bycatch among their fisheries. The United States is considering joining the agreement but currently attends meetings as an observer.

“These birds forage across vast areas of the ocean, so it does take international cooperation to make sure that we are addressing this,” says Mi Ae Kim, a fisheries’ foreign affairs specialist with National Oceanic and Atmospheric Association (NOAA), “and also to make sure there’s fairness across the international fleets.”

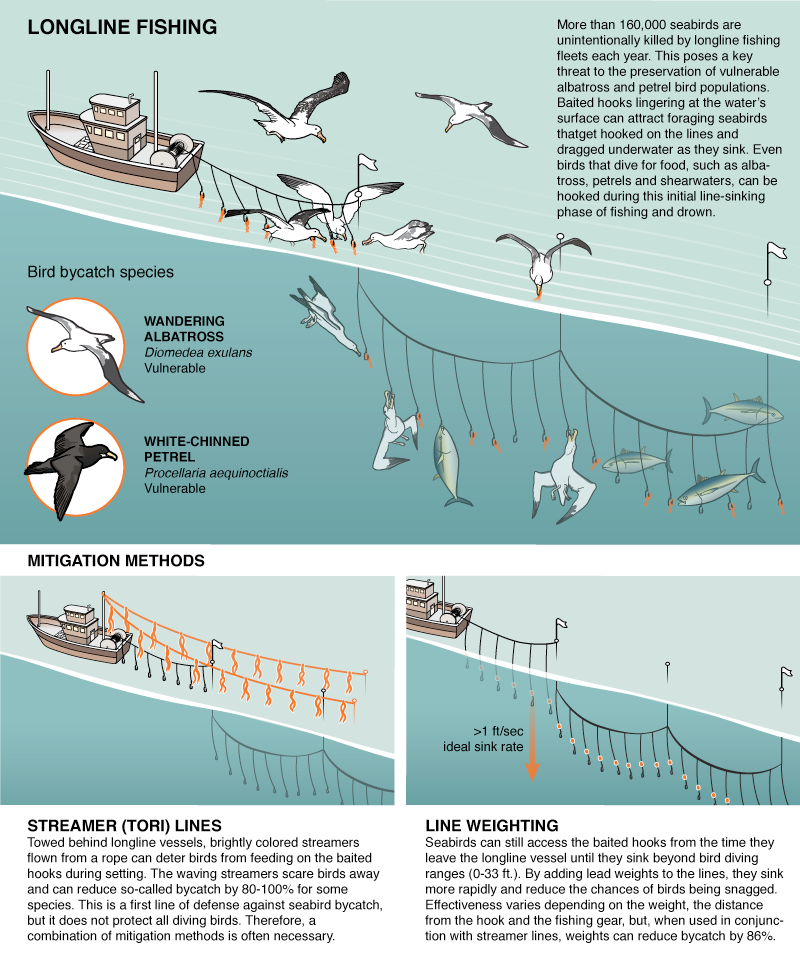

Longline fishing vessels used to catch Pacific tuna or Alaskan halibut were the low-hanging fruit of the seabird bycatch problem, as their lengthy lines often left bait irresistibly reachable to birds skimming the surface for food. To reduce bycatch, brightly colored streamers can be attached to the lines to scare birds that might otherwise collide with them. Vessels can also add weights to the lines so the bait that might lure birds sinks out of reach more quickly. Since the time of the report, it's estimated that hundreds of boats have added streamers or weights, both inexpensive options, though Rory Crawford of BirdLife adds that measuring compliance is the next step in this decades long effort.

Keeping birds away from their lines can be a boon for vessels tired of losing bait or catches to the foragers, too.

One reason seabird bycatch is still a problem is that nobody knows the full scale of the issue. Longline vessels alone still hook and drown an estimated 160,000 seabirds each year, but that doesn’t account for other methods of fishing, nor does it count fishing vessels that might be operating illegally.

“My feeling is the U.S. has been more proactive in the response to bycatch, by finding mitigations and supplying observers” to monitor the number of birds affected, says Breck Tyler, a professor at the University of California Santa Cruz who studies albatross. “If there are endangered species involved, then the fishery can be compelled [by regulators like NOAA or the U.S. Coast Guard] to put observers on and you have a better understanding of the rate of bycatch.”

In addition, at the end of 2015, the NOAA began requiring non-tribal West Coast longline vessels 55 feet and longer to use streamers to reduce bird bycatch, where endangered short-tailed albatross can get caught in fishing gear. Fisheries in Hawaii and Alaska have their own requirements.

Internationally, seabird bycatch is down over the last 15 years, with some very bright spots. One fishery commission operating in Antarctica has deployed a series of mitigation methods, including seasonal closures, night settings and bird exclusion devices, to reduce seabird bycatch among its vessels from thousands of birds annually to zero.

The American Bird Conservancy created a website last year that helps fisheries determine which birds might be at risk of bycatch based on their region and gear type—and which mitigation methods might be necessary to adopt to avoid losing both fish and seabirds.

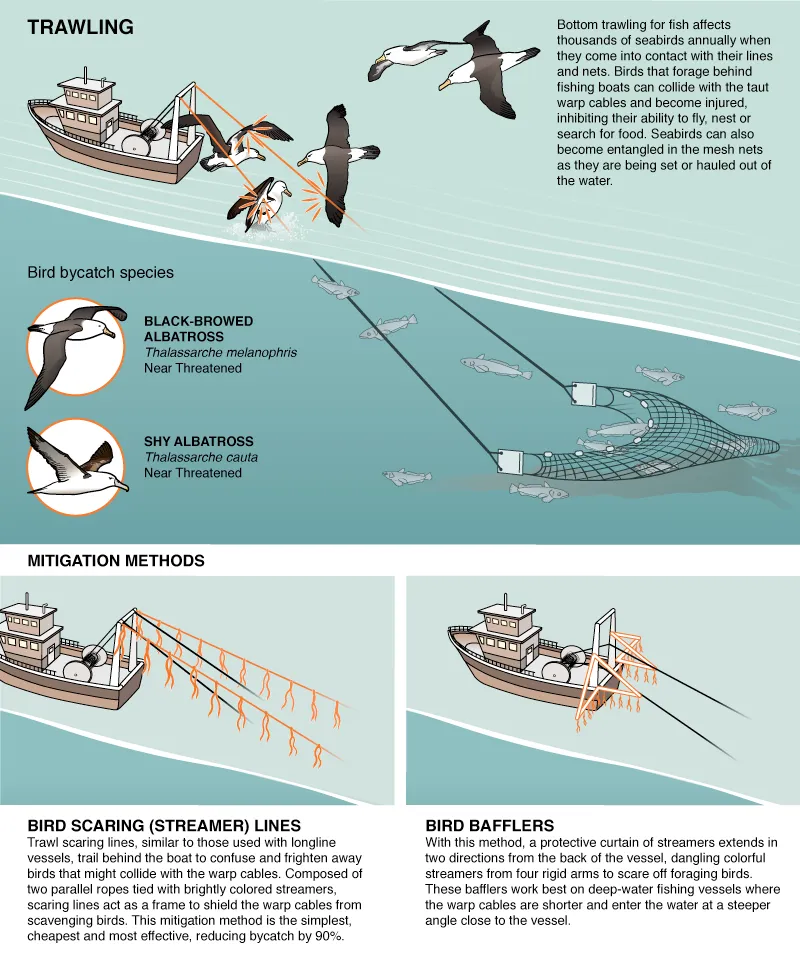

For example, trawling boats that catch fish by dragging a net behind the boat can entangle thousands of seabirds each year. But streamers mounted near the boat or along the line scare away 9 out of 10 birds that approach.

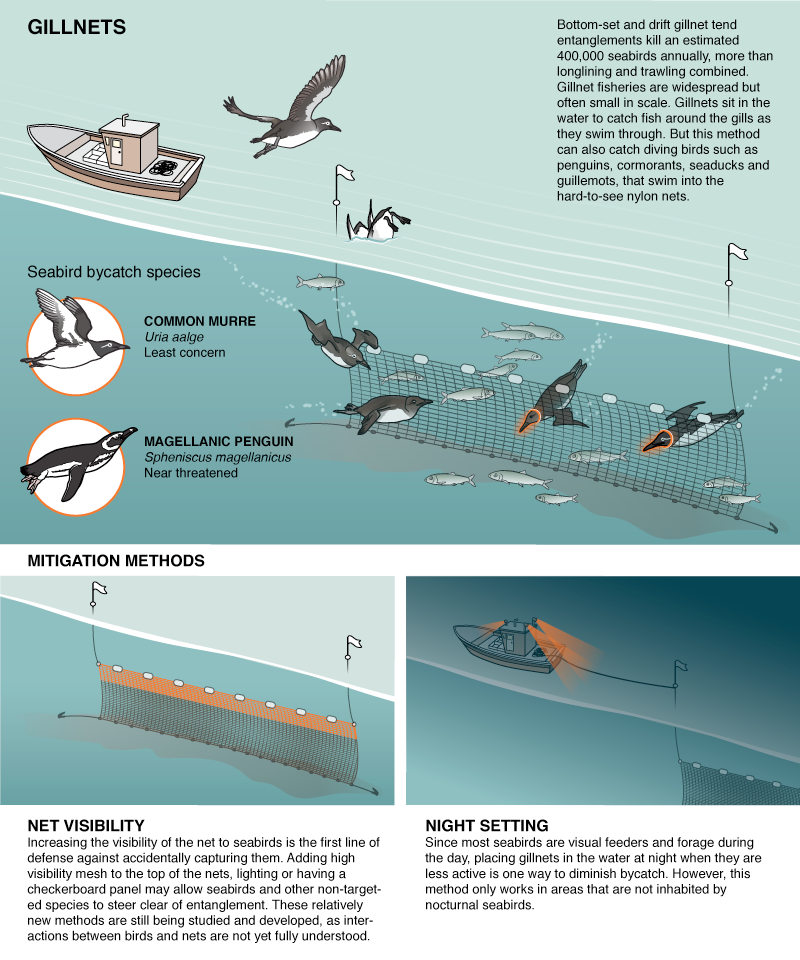

Gillnets that stretch horizontally across an expanse of ocean or on the bottom near coastal areas currently pose the greatest threat to seabirds, with few mitigation options available. An estimated 400,000 birds—including the near-threatened Magellanic penguin—are killed each year when they swim into nets they cannot see.

Increasing the visibility of those nets with thicker mesh or setting the nets at night could reduce those numbers, but there are other factors to consider to ensure the methods don’t overburden fishermen.

For example, colorful lines intended to scare birds away can get entangled with the fishing gear, weighted branch lines could present safety issues for workers and night setting might not work for all species, says NOAA’s Kim.

One new mitigation method introduced at the most recent ACAP meeting uses “hook shielding devices” to reduce bycatch among longline fisheries. One such device, called HookPod, ensconces the hook in a plastic sheath and releases it only a depth that seabirds cannot reach.

“While we have some mitigation measures that we have confidence in, we’re always looking at the effectiveness once they’re implemented,” says Kim.

So, for all its progress, the fishing industry could always do better by the birds.

Below, see three graphics that illustrate the dangers to seabirds and ways those dangers can be mitigated.