The Vibrant Patterns of Portuguese Men-of-War

Beachgoers despise the stinging animals, but photographer Aaron Ansarov finds surreal beauty in them

![]()

Aaron Ansarov experienced some depression after retiring from his post as a military photographer in 2007. But, one of the things that made him happy was walking in his backyard with his son, pointing out beetles, salamanders, praying mantis and other creepy crawlies. “One day, he just said, ‘Daddy, let’s take pictures of them,’” says Ansarov. “That just never occurred to me. That’s when everything changed.”

Ansarov, who lives in Delray Beach, Florida, has three children: a 12-year-old, a 3-year-old and a 2-year-old. He transitioned from photojournalism to commercial photography and fine art, and in the process, he says, he has followed one simple rule—to look at things through the eyes of a child.

“It is very tough as adults, because we get bored. We see things over and over and they are no longer as fascinating to us as they were when we were a child,” says the photographer. “All I try to do is to force myself to see things freshly.”

After exploring his backyard (National Geographic is featuring his “My Backyard” series in a four-page spread in its June 2013 issue), Ansarov turned to the beach, about a mile from his home. There, he became captivated with Portuguese men-of-war.

A man-of-war, if you’ve never encountered one, is a bit like a jellyfish. It is a transparent, gelatinous marine creature with stinging tentacles, except unlike a jellyfish, a man-of-war is a colonial animal made up of individual organisms called zooids. The zooids—the dactylozooid (that brings in the food), the gastrozooid (that eats and digests the food), the gonozooid (that reproduces) and the pneumatophore (an air sac that keeps the animal afloat)—are so integrated that they form one being with one shared stomach. Without their own means of locomotion, the little-studied men-of-war are at the whim of tides and currents. Scientists do not know how men-of-war breed or where their migrations take them because they cannot attach tracking devices to them, but, the animals wash up on shore in Florida from November to February. They turn from purple to deep reds the longer they are beached.

For the most part, Floridians and tourists find men-of-war to be a nuisance. To some, they are disgusting and dangerous even. As a kid, I stepped on one at a Florida beach, and I can attest that the sting is painful. But, Ansarov approaches them with a child-like curiosity. From December to February, he made special trips to his local beach to collect men-of-war. He finds the creatures, with their vibrant colors, textures and shapes, to be beautiful and has made them the subject of his latest photographic series, called “Zooids.”

To give credit where credit is due, Ansarov’s wife, Anna, is the collector. She wears industrial-grade rubber gloves and walks the surf with a small cooler. When she spots a blob in the sand, she grabs it by its non-poisonous air sac and stows it in her cooler with some sea water. Ansarov then takes the men-of-war back to his studio, where he washes the sand from them and lays them one-by-one onto a light table.

“I’m spreading them out and I’m using tweezers to somewhat separate their tentacles and untangle them and then from there just move them around and see what shapes develop,” says the photographer. “I’ll shoot one for five or ten minutes and then put it back and do the same process with the others.”

After the shoot, Ansarov returns the living men-of-war to the beach where he found them and let’s nature take its course. “Either they get swept back out to sea or they die with the others on the beach,” he says.

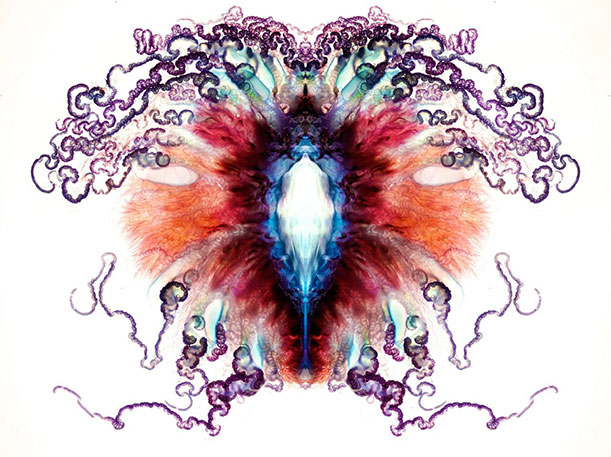

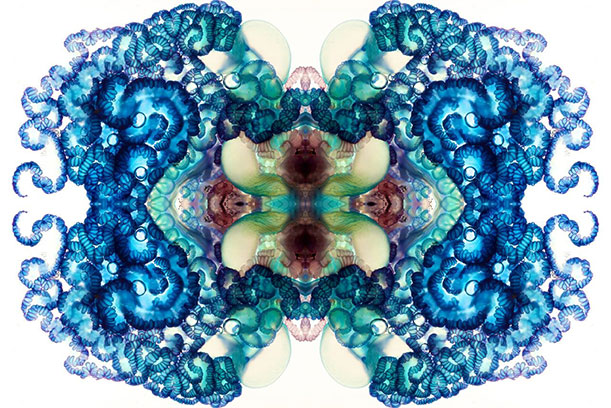

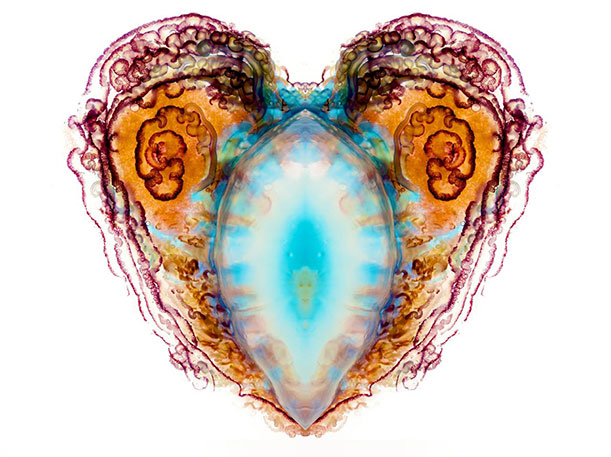

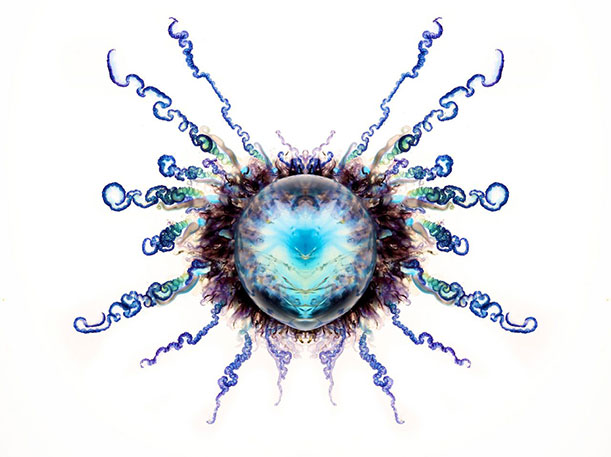

Ansarov often sees air bubbles that resemble eyeballs and tentacles that frame alien-like faces in his photographs. To accentuate this, he “mirrors” each image by opening it in Photoshop, expanding the canvas and flipping it once. In nature, he points out, we respond more to symmetrical things. “If we see two eyes or two arms or two legs, we recognize it a lot more,” he says.

In Ansarov’s Zooids, the anatomical parts of the men-of-war quickly become any number of things: moustaches, antennae, beaks and flared nostrils. The colorful patterns are “nature’s Rorschach test,” the photographer has said. Everyone sees something different.

“One person told me they saw a raccoon playing on drums,” says Ansarov. I see a startled toucan in one—and aliens, lots and lots of aliens.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/megan.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/megan.png)