The Fate(s) of Australia’s Mega-Mammals

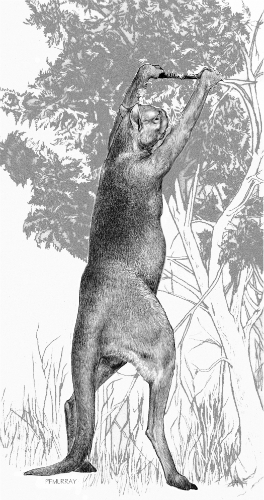

Sthenurus, an extinct giant kangaroo (drawing by Peter Murray, copyright Science/AAAS)

While in Sydney earlier this year, I stopped in at Australia Museum, the city’s equivalent of the Smithsonian Museum of Natural History, and learned a bit about the continent’s extinct megafauna. Australia didn’t have mammoths or saber-toothed tigers, but there were giant marsupials, such as the bear-like wombat Diprotodon and the thylacine (a.k.a. the Tasmanian tiger). On a tour of the museum, I came across a display that said that most of these mega-mammals had gone extinct tens of thousands of years before, the victims of either changes to the climate that led to drier conditions or human impacts, including hunting and landscape burning. The thylacine was the one exception to the megafauna story–it hung on until British colonization and then it was hunted to extinction.

But this story was incomplete it seems, though the museum holds no blame. A couple weeks after I returned to Washington, Science published a study addressing this very issue (for all the megafauna but the thylacine, but we’ll get to the tigers in a moment). Susan Rule of Australian National University and her colleagues analyzed pollen and charcoal in two sediment cores taken from a lake in northeast Australia to create a record of vegetation, fire and climate changes over the past 130,000 years. They also looked at spores of the fungus Sporormiella, which is found in dung and is most prevalent when there are large herbivores in the area.

With this record, Rule and her colleagues determined that there were two great climate upsets 120,000 and 75,000 years ago, but the megafauna had no problems surviving those times. However, between about 38,000 and 43,000 years ago, Sporormiella spores decreased in the record, likely reflecting the disappearance of large herbivores during that time, which correlates with the arrival of humans on the Australian continent. Following the megafauna disappearance, the cores displayed an increase in charcoal, an indicator of a greater frequency of wildfires. “The fire increase that followed megafaunal decline could have been anthropogenic, but instead that relaxation of herbivory directly caused increased fire, presumably by allowing the accumulation of fine fuel,” the authors write. The lack of herbivores in the Australian ecosystem led to changes in the types of plants growing there–rainforests were replaced by sclerophyll vegetation that burns more readily.

So, the likely story is that humans came to Australia around 40,000 years ago, hunted mega-mammals to extinction, which spurred changes to the vegetation growing in the area and resulted in an increase in wildfires.

But what about the thylacine? Only one species, Thylacinus cynocephalus, survived to more recent times, though it disappeared from much of New Guinea and mainland Australia by about 2,000 years ago, likely due to competition with humans and, maybe, dingoes. A few pockets of the species were reported in New South Wales and South Australia in the 1830s but they were soon extirpated. The thylacine’s last holdout was the island of Tasmania, but locals quickly hunted them to extinction, certain the thylacines were responsible for killing sheep. The last known thylacine in the wild was killed in 1930, and the last one in captivity died in 1936. They were declared extinct in 1986.

Recent research has helped to flesh out the thylacine’s story: A study published last year in the Journal of Zoology found that the thylacine’s jaw was too weak to take down an animal as large as a sheep–the animals had been hunted to extinction for crimes they were biologically unable to commit. Though is appears that the hunting may have simply hastened the inevitable. Another study, published in April in PLoS ONE, found that the thylacine had low genetic diversity, which would have made the species more susceptible to disease and further declines, possible leading to extinction.

But is the thylacine really gone? Tasmanians occasionally claim to have seen a thylacine or found evidence of one in the area–in January, for example, two brothers found a skull they claimed came from a thylacine–but none of these sightings has ever panned out with real evidence, such as a clear photo or video. Zoologist Jeremy Austin of the University of Adelaide tested DNA in alleged thylacine droppings collected between 1910 and 2010 but none were actually from a thylacine.

Australian Museum scientists had planned to attempt cloning a thylacine, but those efforts were abandoned years ago. So, for now at least, all of Australia’s mega-mammals will stay extinct.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Sarah-Zielinski-240.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Sarah-Zielinski-240.jpg)