Old Time Portraits of Parasites

Photographer Marcus DeSieno uses antiquated techniques to take pictures of parasites with a mix of citizen science and monster movie panache

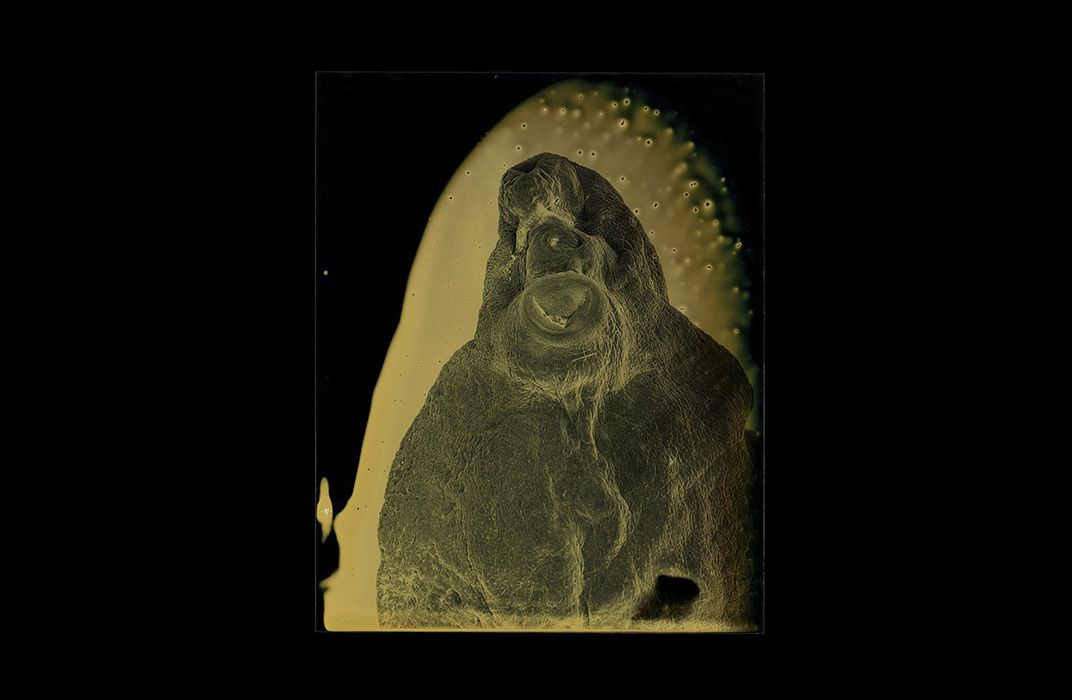

There’s a scene in the 1979 movie Alien. You probably know the one I’m talking about—where the parasitic extraterrestrial grows inside of a man, emerges from his stomach and then eats him. It’s shocking to any viewer, but perhaps no more so than to those who saw the film at a young age. “When you’re five or six and you see that, it’s terrifying,” says photographer Marcus DeSieno, a graduate student in studio art at the University of South Florida (USF).

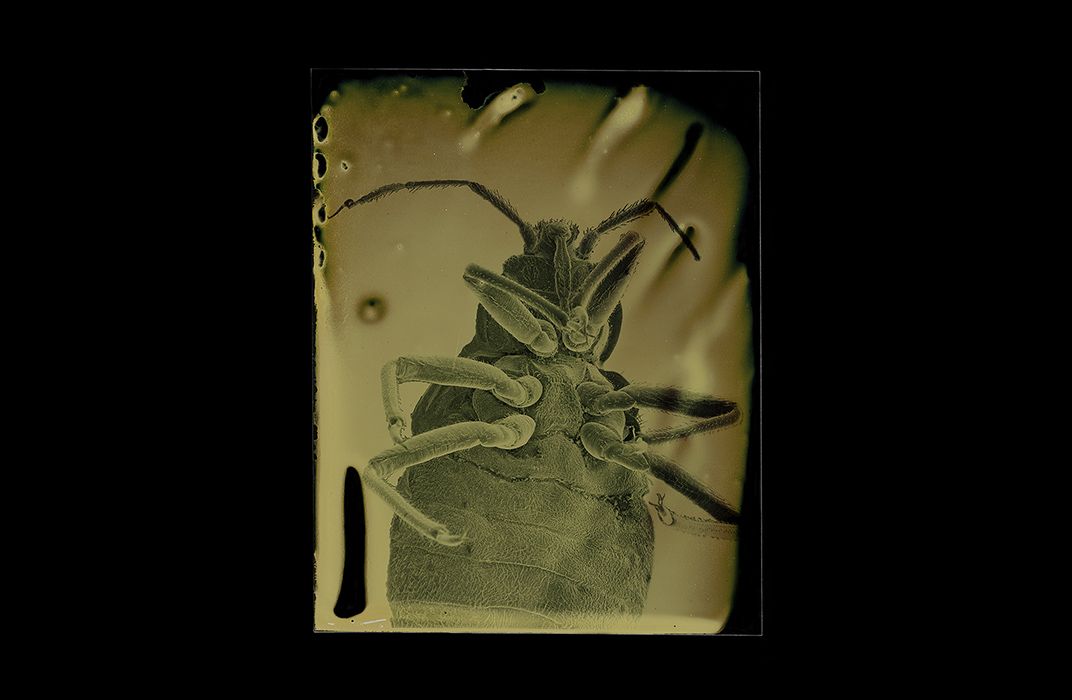

The idea that something potentially lethal could be living inside us or around us isn’t so far fetched. Earthly parasites are all over the place. For DeSieno, who grew up in upstate New York, getting Lyme disease from a tiny deer tick (Ixodes scapularis) was an all too real danger, and Alien only served to drive his fear of parasites home.

Now DeSieno is confronting that fear in a new photography project in which he snaps microscopic shots of parasites that live off of humans and develops the images using the antique tools of 19th-century photographers and scientists.

Parasites might be all around us, but going out to a backyard creek and digging up leeches probably isn’t the most feasible or wise way to find specimen to photograph. So DeSieno tapped the university community for help.

“I started out with broad parameters,” says DeSieno. “This is really about my personal childhood fear of parasites, so it should be human-borne parasites or parasites that infect humans. And the second was whatever I could get my hands on.”

Local parasitologists at the University of South Florida began providing him with specimens. Eventually USF researchers put DeSieno in contact with scientists at the National Institutes of Health. And even Etsy, it turns out, can be a resource for those in search of preserved parasites. From tapeworms to leeches to ticks, soon dead bugs began to arrive on DeSieno’s doorstep.

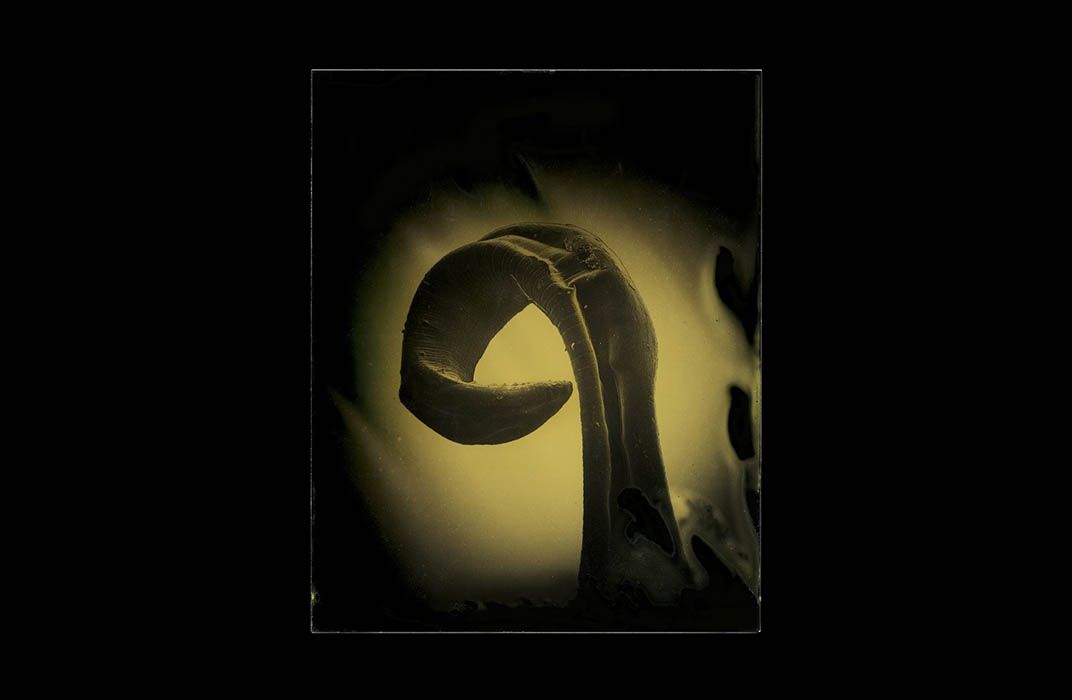

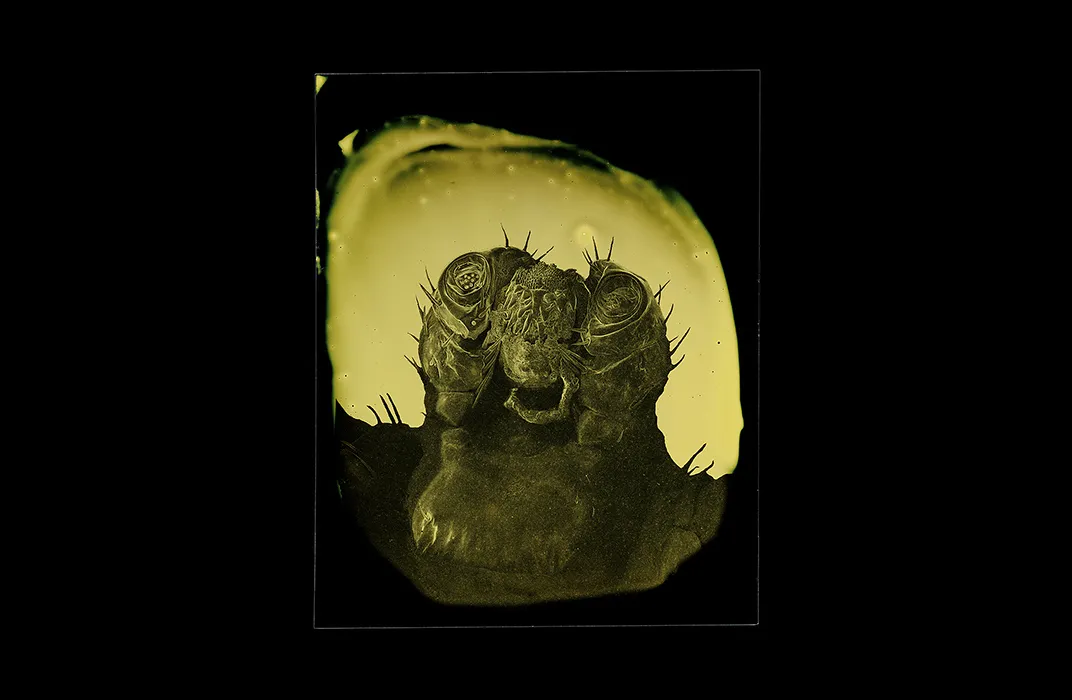

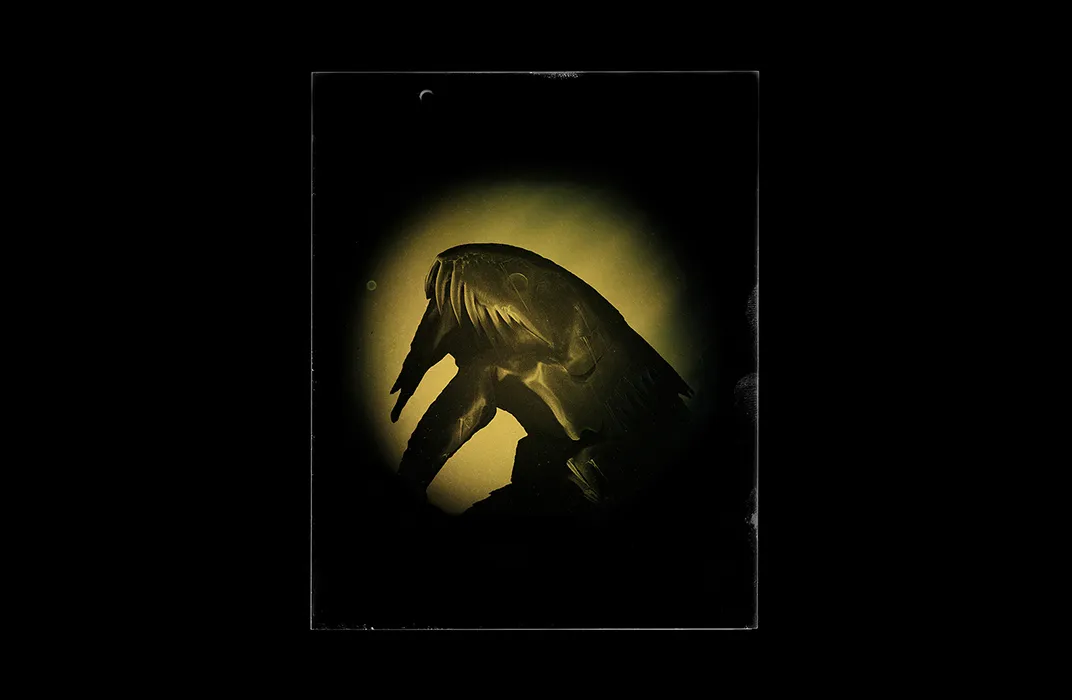

Just how does DeSieno create his spooky photos? When the specimens get to DeSieno, they’re already dead, preserved in alcohol. At USF’s Advanced Microscopy and Cell Imaging Lab, he dehydrates the critters and poses them under the lens of a scanning electron microscope (SEM), with the help of lab technicians. (Looking at a deer tick under the SEM proved particularly cathartic for DeSieno.)

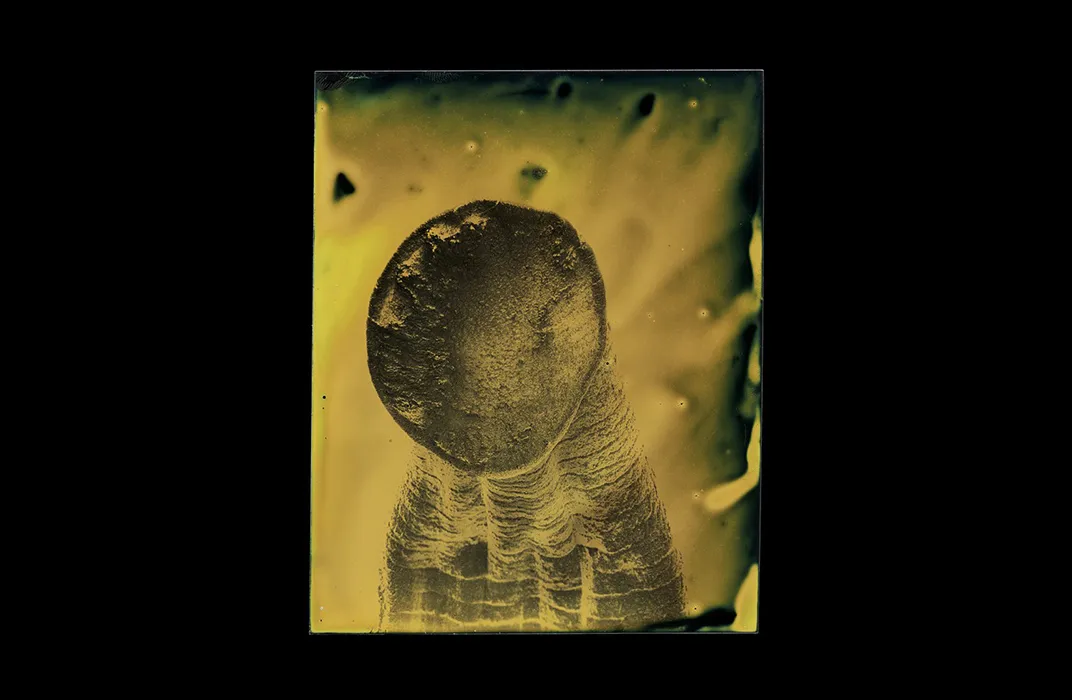

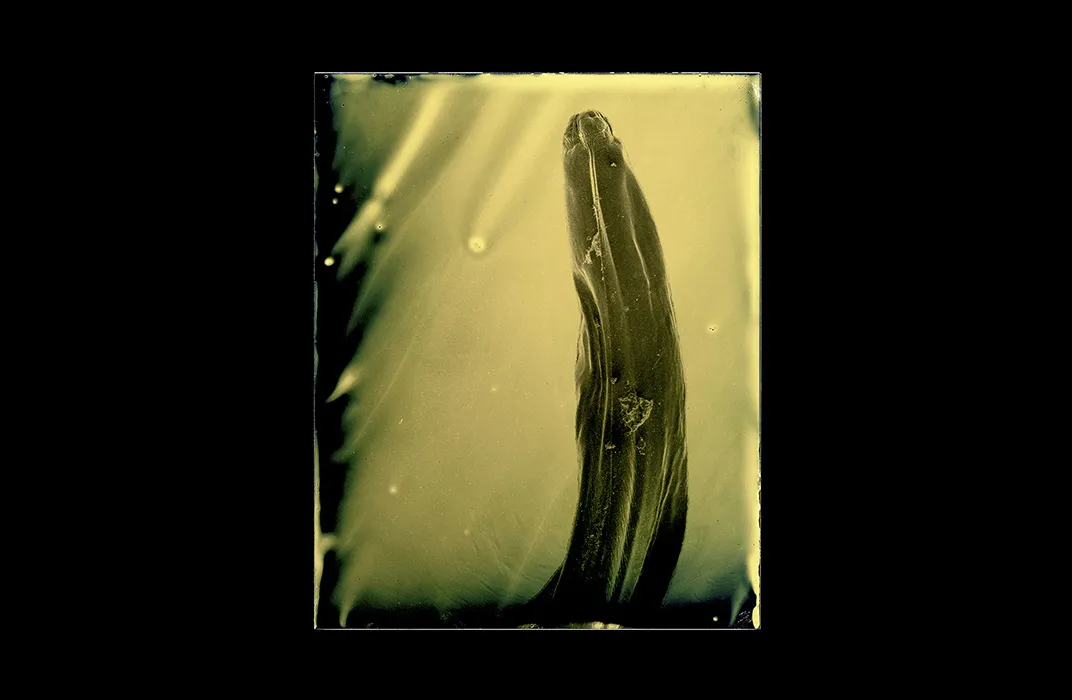

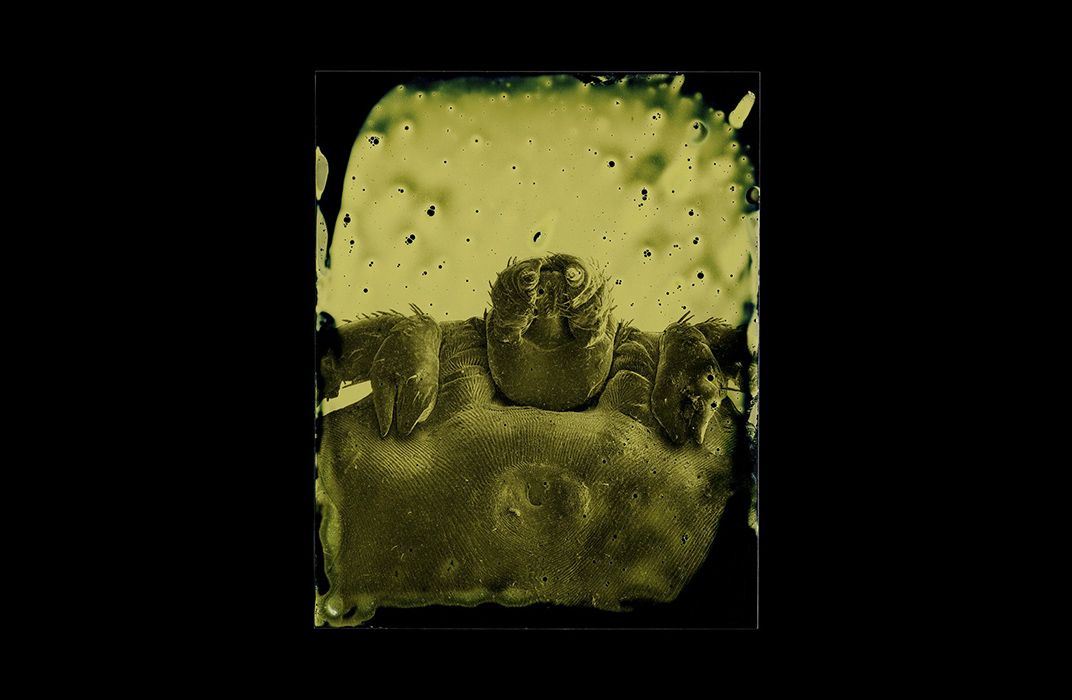

Next, he prints the SEM shot of the bug onto a transparency—in essence a positive piece of “film”— and exposes the image onto a ferrotype plate, a form of early tintype photography popular in the late 1800s.

Back in the day, tintype photography provided a fast, cheap alternative to the wet collodion process, which produced detailed prints from glass negatives. Tintypes replaced glass with metal plates—or more specifically iron plates, in the case of ferrotypes. The plates, which have a thin film of gelatin and silver nitrate, get exposed to light when the camera shutter opens. The plate can then be developed immediately, creating a sort of early form of a Polaroid.

To process the image, DeSieno uses an acid that reduces the silver nitrate to silver particles that form the picture, and once the image becomes clear, he halts development using a standard sodium thiosulfate fixer. This removes the excess silver nitrate and stabilizes the image. “It’s going to come out differently every time you pour a plate,” he says. For the artist, “that creates a sense of mystery.”

The first images he produced came out quite formal and posed, similar to early photographs of botanical and microscopic specimen. But since then, DeSieno has played around at bit. By tweaking the chemistry during development, he can change the coloration—revving up the pukey greens and puss-like yellows to give the image a bit more “funk.” “There’s a mix between the anthropomorphic shots that look like monster movie images and these more formal abstractions,” says DeSieno.

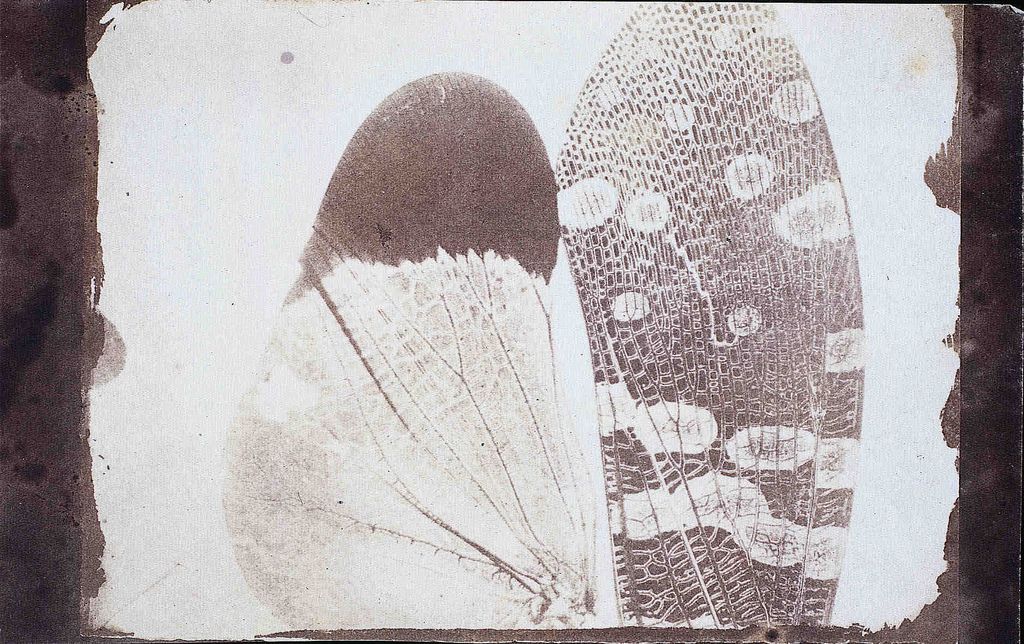

While the project’s initial inspiration may have been personal and modern, the project’s larger themes harken back to photography’s scientific beginnings, to an era of cabinets of curiosity and Western exploration. “Photography has had a long storied history with science,” says DeSieno.

In fact, many early photographers came from scientific backgrounds—whether professional or amateur. And the ferrotype process itself has scientific originators. Adolphe-Alexandre Martin, who described the chemical process behind tintypes, had a day job as a physicist. An amateur astronomer and scientist, Hamilton L. Smith later patented and pioneered the use of iron ferrotype plates using Martin’s process in the United States.

These early innovators used photography to explore the unknown and catalog the world around them, a practice that’s familiar to DeSieno who takes on an amateur scientist role in preparing and photographing the parasites. “I’m taking this image that was made with contemporary imaging technology and combining it with historical process to create a dialogue about photography and history, science and exploration—past and present,” says DeSieno.

Photography was birthed by a period of optimism about science and exploration that remains relevant today even though some circles hold science, like the deer tick, as a scary entity. DeSieno is hesitant to get political in his message, but more than anything he hopes that the images spark curiosity and discussion, rather than fear.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Screen_Shot_2014-01-27_at_12.05.16_PM.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Screen_Shot_2014-01-27_at_12.05.16_PM.png)