How the Human Body Evolved to Throw Fastballs

Our shoulder flexibility allows us to hurl things at high speeds compared to other primates—a trait we likely evolved for hunting two million years ago

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/20130626120308pitch-copy.jpg)

Humans have a number of special abilities not shared by other primates. Being capable of walking continuously on two legs might be the first that comes to mind. The ability to speak, produce written language and engage in complex reasoning are a few more.

One of our most remarkable skills, though, might be one that you rarely consider outside of sporting contexts: the ability to throw small objects fast and hard.

Chimpanzees, after all, are roughly twice as strong as humans, pound for pound, and can jump about a third higher than our finest athletes, but can only throw an object about 20 miles per hour—far slower than an average person, let alone a professional baseball player (who commonly throw in the 90s or even 100s).

Why are our bodies particularly suited to throwing things? A new study published today in Nature by researchers from Harvard and elsewhere suggests that our ancestors evolved this uncommon ability roughly two million years ago as a way of improving their hunting prowess. The newly-evolved skill likely helped early hominids to more effectively hurl rocks or sharpened pieces of wood at prey.

The study began with a biomechanical analysis of what exactly goes on during the human throwing motion, which was conducted using an infrared motion capture system (the same technology often used to create realistic human movements in video games) to look at the deliveries of 20 college-level baseball players as they threw 8-10 pitches. While throwing a ball, a person’s shoulder can rotate extremely fast—at 9000 degrees per second, it’s the fastest movement found in the human body—and the researchers’ previous calculations had shown that this speed couldn’t be explained by the energy stored in the shoulder muscles alone.

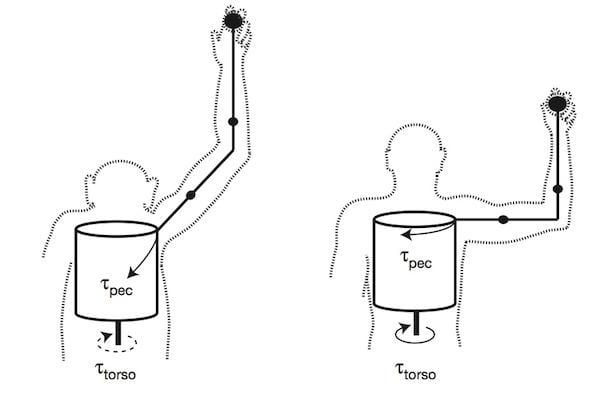

Their analysis showed that the remarkable level of speed generated during the throwing motion wouldn’t be possible without the flexible tendons and ligaments that surround the shoulder. “When humans throw, we first rotate our arms backwards away from the target. It is during this ‘arm-cocking’ phase that humans stretch the tendons and ligaments crossing their shoulder and store elastic energy,” Neil Roach, a biological anthropologist and lead author of the study, said in a press statement. “When this energy is released, it accelerates the arm forward, generating the fastest motion the human body produces, resulting in a very fast throw.” In a sense, these stretchy tendons and ligaments act like the rubber band in a slingshot, gradually storing energy and then releasing it all at once.

The researchers also found that we’re able to use our shoulder tendons and ligaments in this way because of several anatomical features that we all have—and don’t share with any other primates. For one, our low, outward-facing shoulders allow a greater range of motion than chimpanzees’ high, inward-facing ones. Additionally, our high, mobile waists also allow us to rotate our torsos more easily, enabling us to cock our throwing arms farther back, relative to our legs.

The importance of these features and the overall significance of a wide range of motion in producing fast throws was confirmed when the researchers put shoulder braces on the baseball players and let them pitch. With their flexibility reduced, the speed of their throws declined by an average of 8 percent.

The evolution of the anatomical traits that set our throwing skills apart from chimps can be traced to roughly two million years ago, the researchers say, when our ancestors still belonged to a different species (Homo erectus). While it’s impossible to know exactly which selective pressures led to their evolution, the researchers have an idea. “We think that throwing was probably most important early on in terms of hunting behavior, enabling our ancestors to effectively and safely kill big game,” Roach said. “Eating more calorie-rich meat and fat would have allowed our ancestors to grow larger brains and bodies and expand into new regions of the world—all of which helped make us who we are today.”

Eventually, the development of technologies that made hunting easier—starting with bows and arrows, then nets, blades, and eventually firearms—made our skill at hurling objects largely unnecessary. But if the authors are correct, our capacity for such invention stems from the evolutionary advantage given by high-speed throwing. In a sense, throwing javelins, hurling Hail Mary passes, and striking out batters—athletic feats that attest to our physical prowess as a species—are just an evolutionary vestige from our ancestors, retained by our modern selves.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/joseph-stromberg-240.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/joseph-stromberg-240.jpg)