Evolution, A Book That Turns Science Into Art

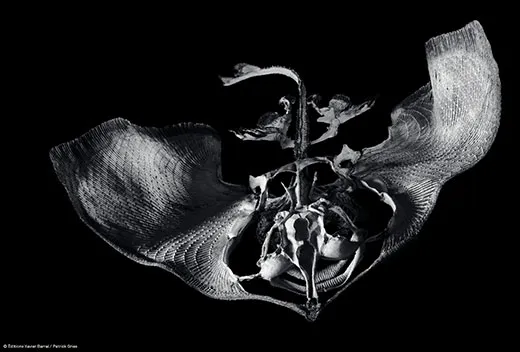

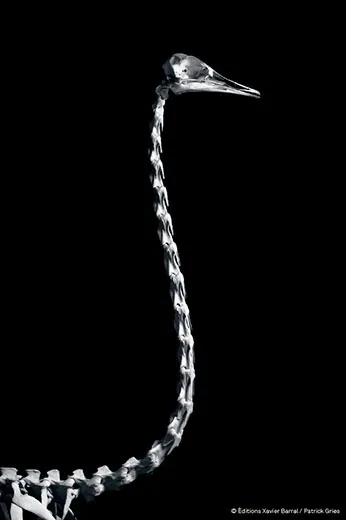

See examples of these beautiful photographs of animal skeletons in our image gallery

Scientists have long used the skeletons of animals to study the relationships among different species. French naturalist Pierre Belon in 1555 included an engraving of a human skeleton beside a bird skeleton in his History of the Nature of Birds to emphasize similarities. Nearly 200 years later another French naturalist, George-Louis Leclerc, Comte de Buffon, compared the skeletons of humans and horses. He wrote in 1753:

Take the skeleton of a man. Tilt the pelvis, shorten the femur, legs, and arms, elongate the feet and hands, fuse the phalanges, elongate the jaws while shortening the frontal bone, and finally elongate the spine, and the skeleton will cease to represent the remains of a man and will be the skeleton of a horse.

Charles Darwin also used skeletons of living species–along with live and taxidermied specimens and fossils–as he developed his theory of natural selection.

It would appear that skeletons, then, would be a great tool for teaching evolutionary theory. But I wasn’t expecting them to be so beautiful.

The first thing you notice when you see a copy of Evolution by Jean-Baptiste de Panafieu are the photographs. One of my magazine colleagues called these stark black-and-white images of animal skeletons, by Patrick Gries, “science porn.” An artist friend drooled over the beauty in the imagery. (See four examples from the book in our photo gallery below.) It could be incredibly easy to own this book and never read the text.

But that would be a shame. The book, brilliantly translated by Linda Asher from the original French, is organized into 44 easy-to-read essays about various topics in evolution, from history to modern theory, each illustrated by a set of skeleton photographs. The co-evolution of predator and prey species, for example, includes images of a leopard skeleton attacking a screwhorn antelope, a golden eagle swooping down on a rabbit and a red fox pouncing on a common vole. The text is full of details and stories that will be new even to readers who are familiar with the topic of evolution. But everything is explained well enough that those who have not read much about evolution before will not be lost.

Evolution may seem familiar; in 2007, the book was released in large format and quickly sold out after a selection of its images ran in the science section of the New York Times. This new version is a much more shelf-friendly and reading-friendly size, and it includes a handful of new images. The book would make a great last-minute holiday gift for the science or art lover on your list or just a fine addition to your own library.

(I can hardly bring up the topic of evolution without mentioning Smithsonian magazine’s January issue, now online. With it, we created something called Evotourism–a new type of travel focused on evolution. We’ve started off with 12 destinations, from the Jurassic Coast of England to Australia’s Kangaroo Island. You can learn about evolution by digging for your own fossils, viewing some of the world’s weirdest species ever to evolve, even helping scientists study the co-evolution of a predator and its prey. And if you’ve got your own Evotourism suggestions, we want to hear them.)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Sarah-Zielinski-240.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Sarah-Zielinski-240.jpg)