Step Inside a Virtual Building of the Future

Architects are embracing virtual reality and the complex designs they can create there

:focal(342x137:343x138)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/c1/bb/c1bbf76f-0c80-4589-89ba-0ec425eb4a80/botswana-innovation-hub_aerial_shop-architects-pc.jpg)

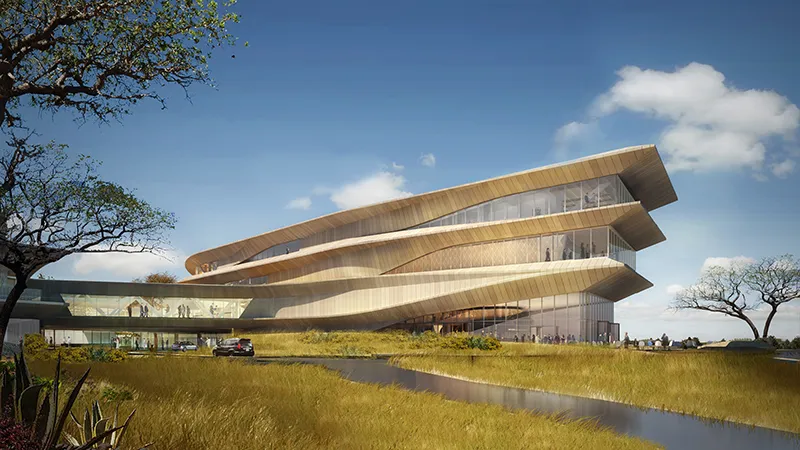

On a loop road on the north side of Gaborone, Botswana, a three-pronged, glass-faced structure sits like a grounded starship. It’s the Botswana Innovation Hub, a new LEED-certified facility for technology research and development, funded by the Botswanan government in an effort to bring tech jobs to an economy long dominated by the diamond trade.

A walk through the inside shows spacious lounges, conference facilities, a library, medical research labs and startup incubators. Footbridges connect the different wings.

Today, this whole 270,000 square-foot complex is just a vision, viewable through an HTC Vive virtual reality headset. The location in Botswana now contains a partially completed structure, exposed beams stretching upward and out in the general framework that will become the building.

SHoP Architects, the firm behind the innovation hub, uses this kind of visualization for several purposes. SHoP and other forward-thinking, trend-setting architecture and engineering firms are embracing virtual and augmented reality as tools for creating better buildings, more efficiently. From his office in New York, SHoP director of virtual design and construction John Cerone can stroll the halls and rooms of the building, seeing it in detail that would be indiscernible from normal architectural drawings or even models.

“The idea that you can use an immersive rendering, that [clients] actually feel the space, they’re in it, they occupy it, there’s depth perspective,” says Cerone. “It’s an incredibly powerful tool, a communication tool, to basically see and feel the design before a lot of effort and money and time is spent building it.”

Most simply—and this has been happening for years—virtual reality provides a way to share with clients a representation of a building before it’s commissioned, or in the process of selling space within it. Meetings and collaboration happen faster and more accurately as the parties—whether distant or in person—get a more accurate idea of what each other is thinking.

There are a few examples of software used to build these virtual representations, says Jeffrey Jacobson, who helps architecture and engineering firms develop and train personnel to use virtual reality. The two most dominant are video game engines known as Unreal and Unity. “Those are sort of the Coke and Pepsi,” says Jacobson.

Other programs are tailored more specifically to building design. Autodesk, which created its own version of a game engine called Stingray to visualize buildings, built a sort of short cut called LIVE. LIVE is used to automatically create a three dimensional visualization of a space designed in Autodesk’s Revit Building Information Modeling software and translate it into Stingray, without requiring a lot of new skills.

“If you’re an architect or an engineer or a construction professional, you don’t have to pick up a big training manual for how to convert CAD data to make it work in a real time engine,” says Joel Pennington, principal designer of LIVE. “If you’re using Unity or Unreal, you have to do that.” LIVE allows users to click through a building, evaluating particulars like the perceived height of a railing, the way the sun will shine through at different times of year, and more.

But beyond just seeing what’s been designed, points out Cerone, virtual reality can alter the whole architectural process, from design to construction, even to maintenance after a building is completed. Architects don’t have to use software to translate their drawings into renderings; they can design in three dimensions in the first place. SHoP has trained employees in virtual design and construction, as well as laser scanning to digitize existing interior spaces, which can give the designers an idea how the project is progressing.

It all gets more important as the spaces we design and build get more complicated. “It’s especially useful when it’s with a strange kind of a space, like an atrium of a building, or a lobby,” says Jacobson. “They’re always irregularly shaped, it’s always something new, and you really just can’t imagine it any other way and get the scale right.”

Inside the walls, heating and ventilation, electrical systems, plumbing and alarm systems all have to fit together like a three-dimensional puzzle.

“As we see that building design continues to increase in its requirements and complexity, the construction industry has more pressure put on it as a result,” says Pennington. “The ability to leverage technologies like virtual reality to find issues early on before they’re an issue during construction is … giving runway to the process so that we’re saving time and effort up the entire pipeline.”

It doesn’t stop with the design, or with virtual reality. Augmented reality will start to provide faster more accurate ways to build. Digitally modeled structures can be fabricated with computer-controlled machines. Then, instead of relying on a drawing to figure out where to install something, construction workers could see a digital version, overlaid via a tablet or other screen right onto real life. Operations and maintenance staff, too, will use augmented reality in similar ways, to simplify upkeep.

“With augmented reality, you can have this fake x-ray vision that lets you see inside the walls,” says Jacobson.