City Governments Are Collaborating With Startups, and Acting Like Ones Themselves

By establishing offices that promote innovation, cities are taking more risks than ever before

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/95/dd/95ddf55d-95ea-44f5-bf97-527136f20306/city-hall-to-go-page.jpg)

Americans often consider local city governments to be lethargic and generally averse to change. In recent years, however, several cities, including Boston, Philadelphia and San Francisco, have established groundbreaking new offices, focused specifically on innovation and risk-taking, that are dispelling this long-held stereotype.

In 2010, Boston established the Office of New Urban Mechanics, an agency in the broader mayor's offices dedicated to connecting the city with startups developing inventive technology that could improve civic stress points. For example, the city is working with TicketZen, a local startup, to streamline the experience of paying parking tickets. Using the TicketZen mobile app, residents can simply scan their parking ticket and pay quickly on the spot. The office also collaborates with existing government departments, including the legal, finance and procurement teams, to develop projects. Urban Mechanics partnered with the public works department and design firm IDEO to develop Street Bump, an app that captures and crowdsources data on road damage and needed repairs. Inspired by the work being done by the team in Boston, Philadelphia opened a similar office in 2012.

The teams in Boston and Philadelphia have adopted the “fail fast, fail often” ethos of the startup world—aiming to quickly learn what practices and tools work best to address challenges, from public school registration to recidivism.

“We’ve been designed to have entrepreneurial agility,” says Chris Osgood, co-chair of Mayor Marty Walsh's Office of New Urban Mechanics in Boston. “Part of our role is to be experimental, with a public expectation of risk-taking and failure, as long as it’s done with good intentions.” According to the Philadelphia team's lead Story Bellows, Mayor Michael Nutter has a similar outlook. He's been known to tell his Urban Mechanics team, “If you don’t fail, you’re not trying hard enough.”

Philadelphia was the first city to partner with Citizenvestor and post a project on the crowdfunding platform, which focuses specifically on civic works. Some might consider the experiment a failure. The project, called TreePhilly—an effort to plant trees around the city—did not reach its fundraising goal. But the experience, Bellows says, introduced different departments to new funding sources, and also taught those involved that future crowdfunding projects should be more tailored to a particular community in order to promote engagement. The initial pilot paved the way for more campaigns that went on to be successful, including a community garden at the River Recreation Center. The partnership with Philadelphia also helped to launch Citizenvestor, a Tampa-based startup, on a larger scale, leading to further partnerships with 170 other municipalities, including Chicago and Boston.

One experiment that has been replicated in several other places is Boston's City Hall to Go, a mobile truck derived from the success and popularity of food trucks, that now stops in neighborhoods and offers direct access to civic services, like requesting parking permits and paying property taxes. The "mobile City Hall" offered 50 services and completed 4,050 transactions by the end of 2014, leading to similar programs in Vancouver, British Columbia and Evanston, Illinois.

The risks by Urban Mechanics are calculated ones, of course, and in taking them, governments exercise greater freedom to test different strategies and tools. “The office allows the government to have the dexterity to operate on day-to-day operations and to carve out resources that focus on innovation.” says Nigel Jacob, a co-chair in Boston. “Unless people are focused on the broader future, the immediate concerns of tomorrow will take precedence.”

In each city, the teams have executed on the Urban Mechanics mission by holding hackathons, developing apps and creating startup accelerator programs that offer startups early stage funding, mentorship and access to industry expertise. The fruits of these labors are intended to have powerful, long-term impacts—serving as a visionary look into how the cities could function more effectively moving forward. The agencies have also played a major role in breaking down any traditional notion that government practices are antithetical to innovation—serving as a key liaison between the city and entrepreneurs.

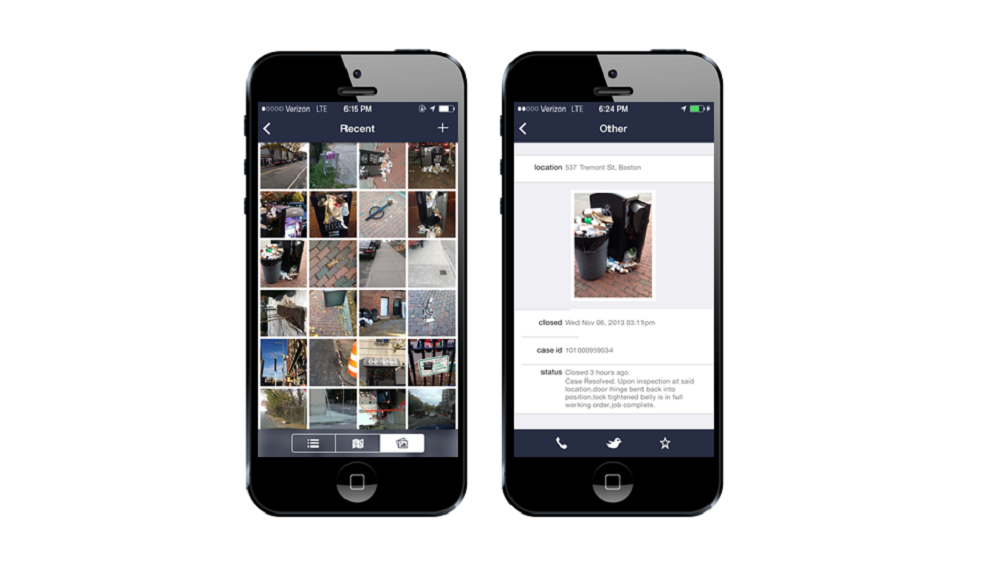

In Boston, one of Urban Mechanics’ major focuses has been leveraging technology to actively engage residents in city issues and increase the transparency of government practices. “How do we get more residents to work with government to be our eyes and ears?” says Osgood. Citizens Connect is a mobile app the team launched with local company Connected Bits that allows citizens to report problems, such as damage to road signs and potholes, by choosing a category from graffiti to litter to broken streetlighting, uploading a photo and writing a description. When it launched in 2010, 6 percent of service requests were created through the app. By 2014, that number more than quadrupled to 28 percent.

The team has seen strong adoption and support for its other offerings—solar-powered public benches with charging stations called Soofas developed with MIT Media Lab and the online GPS tracker Where’s My School Bus?, created with Code for America, that quickly enables parents to spot their child’s location. In addition to building specific products, Urban Mechanics has started HubHacks, an annual hackathon open to coders interested in improving the city government's digital tools and services. The latest HubHacks focused on streamlining the permit approval process for local businesses; Civic Panda now allows constitutents to track a permit application after submission.

Urban Mechanics and the Mayor’s Office in Boston have made an immense effort to share city data on topics ranging from pothole requests to crime incident reports with anyone interested in using it to create new products or analyses. The office currently prioritizes projects that fall in four sectors: education, engagement, streetscape and economic development.

To further strengthen relationships with local startups, Mayor Walsh recently appointed Rory Cuddyer as Boston's first ever "startup czar," at the helm of the city's StartHub program supporting entrepreneurs. Cuddyer believes the government should help startups connect with key resources including potential funding and office space, while also addressing unmet concerns. "How do we act as a connector and convener?" he asks.

Philadelphia's Urban Mechanics team is focusing on public safety. In 2013, the agency received a million-dollar grant from the Bloomberg Philanthropies Mayor’s Challenge and, working with Good Company Ventures, used it to establish FastFWD, an accelerator that selects 10 to 12 startups each year to work with the city on specific endeavors.

With the help of the Wharton Social Impact Initiative, a group at the University of Pennsylvania's Wharton School of Business focused on leveraging business acumen to address social issues and community problems, Urban Mechanics changed the way the city presented projects to companies. Historically, the government would issue a Request for Proposal, or RFP, detailing the specs of a particular problem, and hire an organization to complete it. While this method is still used, the team reframed its challenges, describing them as broader business opportunities for growth rather than problems to be solved, in order to appeal to startups and talk in the same language entrepreneurs use.

“[Until now] We in government have just not gone through the mental shift, of making things comprehensible to the people we’d like to work with,” says Jacob. There is a lot of de-jargoning to be done in order to faciliate dialogue between city governments and external partners.

Two projects from the first FastFWD class are currently being piloted. Jail Education Solutions, a Chicago company, is using tablets to offer inmates additional education. Textizen is another FastFWD participant that's part of an onging partnership between the city of Philadelphia and Code for America. It is a city-wide initiative that poses questions about public transportation, facilities and recreation to citizens in bus stops, parks and other public places. People have a chance to text their responses to a number that is displayed. The effort has enabled the city to have a digital town hall of sorts and give citizens an opportunity to easily contribute their opinions.

The trend for city governments to leverage startups has taken root on the West Coast too. The San Francisco Mayor's Office of Civic Innovation (MOCI), created in 2012, is headed by Chief Innovation Officer Jay Nath. Nath was appointed by Mayor Edwin Lee and is the first to hold this type of position for a city. MOCI is focused on infusing city government with an entrepreneurial spirit. "We see ourselves as a startup within government—as a bridge between the broader community and people who have great ideas, resources and methodologies. How do we bring that ingenuity and creativity to bear in the public sector?" says Nath.

In September 2013, Mayor Lee and Nath partnered with the White House to launch the city’s Entrepreneurship-in-Residence program, which has since welcomed six startups for four-month partnerships with the city. The startups have worked on key issues, such as tracking neighborhood air quality and providing emergency notifications.

“San Francisco is home to the world’s greatest entrepreneurs, the ones who have ‘disrupted’ numerous industries, and we are bringing those same disruptive technologies to improve delivery of city services for our residents,” says Lee, in a press release.

Prior to the launch of the program, one area of need identified by the staff of the San Francisco International Airport (SFO) was helping the blind and visually impaired navigate the complex layout of the airport. Of 200 startups that applied for the program, Indoo.rs, an organization based in Vienna, Austria, focused specifically on creating interactive indoor maps that could be accessed via mobile devices. After being selected, Indoo.rs worked with SFO and LightHouse for the Blind and Visually Impaired, a local nonprofit, to build an app that leveraged audio-based beacons within Terminal 2, enabling visually impaired passengers to walk through the venue independently. The beacons highlight the location of restrooms, restaurants and power outlets.

The Entrepreneurship-in-Residence program is one of many efforts spearheaded by MOCI which was created to promote private-public partnerships and develop fresh strategies for civic challenges. Nath has established an annual Innovation Fellowship program that welcomes creative professionals from other sectors, like technology and media, for a stint at City Hall and helped implement an open data initiative that increases access to civic information. MOCI is also building Living Innovation Zones around the city; these zones are temporary installations that call attention to intriguing science and technology. The first of these—a partnership with the Exploratorium—invites passersby to whisper messages through two large satellite dish-like objects positioned 60 feet apart.

"We aim to work with community partners in novel ways," Nath says, "so people can understand our community isn't just a feedback loop, we can co-create together." MOCI, like the Offices of Urban Mechanics, also serves as a testing ground for new ideas, incubating products and, if they prove successful, implementing them on a larger scale.

Across these cities and others, including Austin and Detroit, a formal civic body to connect with startups and entrepreneurs has pushed governments to become more accessible. In Austin, the city's Innovation Office has focused on improving internal use of technology within local government, making tablets the go-to device for city council to quickly search and access digitized records. The Peak Performance team in Denver, which works across departments and evaluates general practices, has been tasked with making city government more "customer-centric." As described on its website, "Peak’s goal is to transform government from antiquated, bureaucratic and wasteful systems into a customer-driven, creative, sustainable and data-oriented government."

In many ways, governments have taken a cue from large corporations, which are increasingly hiring Chief Innovation Officers. In 2012, 43 percent of companies, including Samsung, Procter & Gamble and Estee Lauder, had established the role of Chief Innovation Officer—a person focused on spearheading new ideas and growth. These executives keep an eye out for fresh thinking within the company and search for breakthrough ideas from consumers and external resources. Additionally, they seek out creative ways to address existing business challenges and offer strategies to integrate innovative practices in daily work. State and city governments have followed suit with more than 20 cities also supporting Chief Innovation Officers, who search for new ways of collaborating across teams and addressing civic questions.

As technology platforms continue to evolve and city resources remain limited, a concerted effort to work with entrepreneurs with creative ideas is vital for cities to grow and sustain effective services for their residents. “When you consider the scale of problems that we take on in cities, poverty and equity and the range of issues we face, business as usual is just not up to the task, we need teams committed to exploring the future,” says Osgood.

The take-home message, says Bellows, is that city governments shouldn't be alone in tackling daunting civic problems. “We are trying to solve some of the most complex challenges in our society, and there are so many people and organizations and institutions that have the capacity to help,” she says. “It’s our responsibility to take advantage of what’s out there.”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/profile.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/profile.jpg)