With $20 And Some Cardboard, You Too Can Enter Google’s Virtual World

A new project from the tech giant hopes to entice developers by creating a low-cost platform users can assemble on their own.

Add immersive virtual reality to the long list of things smartphones can do.

The sleeper hit of Google’s recent I/O developers conference was an unassuming bit of cardboard and other inexpensive bits and bobs that, when assembled and paired with an Android smartphone, can take you to an interactive 3D world.

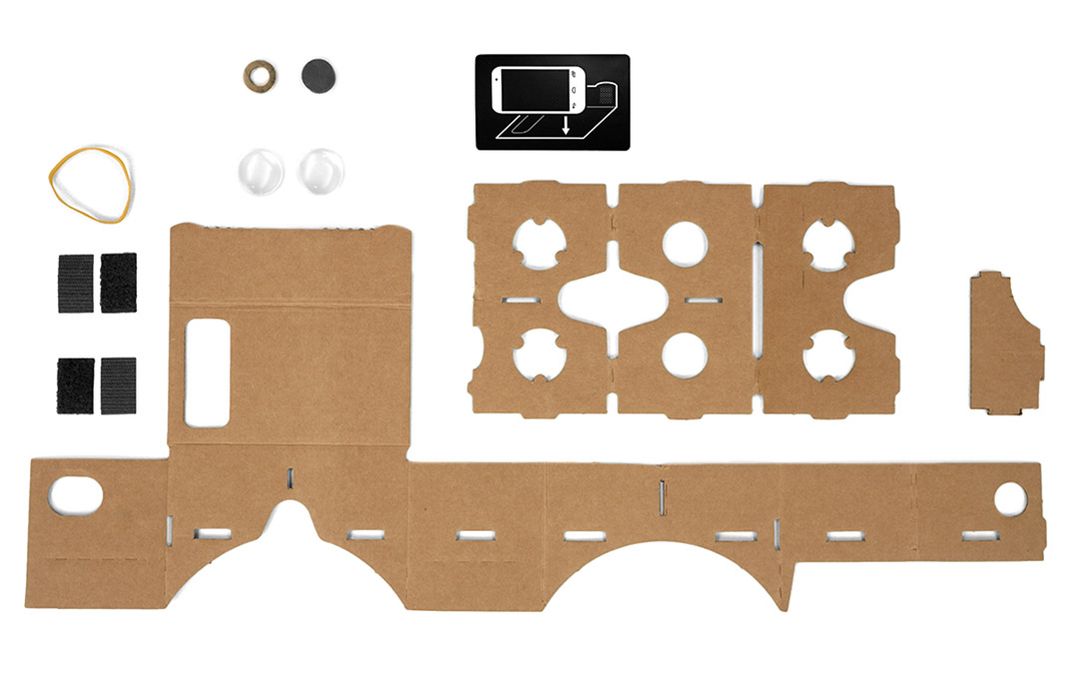

Google has dubbed the project “Cardboard” because the visor component which houses the phone can be constructed from simple materials. The company handed out pre-cut corrugated kits at its conference, but you can make your own out of a pizza box or other materials using a printable template available on the project’s Web page. You’ll also need a pair of inexpensive lenses, to focus your vision and create the 3D effect, as well a magnet and washer, which interact with the magnetometer (compass) in the phone to create a button that lets you navigate the virtual world.

If you don’t want to construct your own headset, companies are already assembling and selling their own kits, starting at around $20. And fancier 3D-printed versions are surely soon to follow, since the project is open source and Google says it doesn’t intend to sell headsets. Instead, Google is focusing on the Cardboard app, which for now lets users fly around Google Earth and view 360-degree photos, using their cardboard-rigged head intuitively to look around. The app also gives users access to a range of other features: You can view 3D YouTube videos, tour the Palace of Versailles or participate in an immersive animated short. Other content will soon follow, since Google has opened the platform to developers around the world to create new features in app form, via the Android OS, or on the Web, via Google’s Chrome browser and HTML 5.

The reaction? An almost immediate jump by consumers and corporations alike to replicate the headset themselves—a response that surpassed the developers' expectations, says Christian Plagemann, a senior research scientist at Google who presented the project at Google’s I/O conference.

“Two hours after we put everything online, people had already produced their own [headsets],” Plagemann told Smithsonian.com. “Some even used cardboard toilet paper rolls.”

Less than a day after Cardboard’s announcement, at least three online stores were selling their own Cardboard headset kits; many sites that sold lenses that could work with the kit ran out of stock.

Much of the appeal and potential of Cardboard comes from its low price point, assuming you already have an Android smartphone. Other high-profile virtual reality projects, like Oculus Rift (which Facebook recently purchased for $2 billion), and Sony’s Project Morpheus aren’t yet commercially available. And while they will likely have better hardware than what’s found in the average smartphone, they’ll also cost hundreds of dollars, which will likely limit their user base.

Cardboard, however, was created by David Coz, a Paris-based software engineer at Google’s Cultural Institute, which focuses on creating tools that bring art and culture to everyone. To meet those goals, Coz and others working on the project had to keep the hardware as inexpensive as possible. Hence the use of cardboard, a magnet, a washer, some Velcro, and a rubber-band.

Yet Mark Bolas, associate professor and director for mixed reality research at the University of Southern California, points out that the ideas behind Google Cardboard aren’t exactly new. His team created a very similar kit two years ago called FOV2GO that uses cardboard or foam board and similar lenses. He points out, though, the lenses his team uses have a wider field of view, which he says creates a more immersive experience.

But Bolas and his team seem pleased that Google’s platform is similar to what they’ve been working on.

“Our mandate for the last three years has been to find ways to get low-cost [Virtual Reality] into everybody’s hands,” Bolas told Smithsonian.com. “We spent a couple of years figuring out the lowest-cost system we could come up with that would still give people that feeling of immersion. We think we’ve influenced the industry across the board.”

Bolas isn’t particularly partial to Google’s design, however. Palmer Luckey, founder of the more gaming-focused Oculus VR headset once worked at Bolas’ lab at USC, as did the founders of Survios, who are working on virtual reality games that can also track the movement of a user's body and limbs.

But aside from its simplicity, it’s the developer push from Google that really gives Cardboard its added potential. A few in-house developers can make a great app or game. But Google hopes developers will create their own virtual reality content. And with thousands of people currently developing for Android and Chrome, the company could quickly find itself with the most substantial and diverse virtual reality software library out there—so long as they can entice enough of those people to create and code for the new platform.

And rather than competing with other virtual reality devices, Cardboard could also help kick start the nascent market. Immersive virtual reality isn’t something that most people have truly experienced, so expensive dedicated VR devices could be a hard sell to the average consumer. But once Google’s low-cost headset becomes more widespread, users may be more inclined to upgrade to more complex hardware.

Both Bolas at USC and Plagemann at Google stress that keeping platforms open is important to getting virtual reality into the hands of mainstream consumers over the next few years.

“With everyone having these smartphones in their pocket, basically billions of people, with very little extra cost, could have [virtual reality] experiences,” Plagemann says. “We thought that the quickest way to have an impact was to just make it open and go really broad.”

And few technology companies have a broader reach than Google, which is why Bolas, who has been working on virtual reality since the late 1980s, is happy to see big consumer tech companies getting involved.

“There’s no way we can have an influence like that Google has,” Bolas says. “We’re proud to have started it, but now we’re kind of awed to see what Google can do with [virtual reality].”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/unnamed.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/unnamed.jpg)