How Fanny Blankers-Koen Became the ‘Flying Housewife’ of the 1948 London Games

Voted female athlete of the 20th century, the runner won four gold medals while pregnant with her third child

:focal(610x123:611x124)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/8c/e3/8ce3ce22-6856-4fd4-8350-dea411daf114/dbs_heqwaaavvax.jpeg)

The last time London hosted the Olympics, the scarred city hadn’t yet recovered from the ravages of World War II. In 1948, after a 12-year hiatus from the Games, the sporting world hadn’t recovered, either. Neither Germany nor Japan were invited, and the Soviet Union declined to participate, Stalin believing that sports had no place in communism.

London built no new facilities or stadiums for what were called the “Austerity Games.” Male athletes stayed in Royal Air Force barracks, while women were housed in college dormitories. All were told to bring their own towels. With postwar rationing still in effect, there were immediate complaints about the British food. A Korean weightlifter lost 14 pounds while in England, and the Jamaicans were extremely displeased and “kicking about the poorly seasoned foods.” Rumors of food poisoning ran rampant, as numerous athletes suffered debilitating stomach pains, but British public relations officers ascribed the incidents to “nervousness,” noting that doctors had detected “nothing more than a mild digestive disorder.” Still, English athletes chose to consume unrationed whale meat, and American reporters who arrived in advance hoped Uncle Sam might send enough steaks, eggs, butter and ham for everyone.

A 57-year-old gymnastics official from Czechoslovakia became the first Olympic political defection when she refused to return to her Communist bloc nation following the Games. There was a row when the International Swimming Federation declared that athletes from Northern Ireland could compete only for Great Britain, and the Irish withdrew from the swimming and diving competition in protest. (They’d already lodged a protest when officials declared that the state be designated “Eire” rather than Ireland, as the team had wished.) As it turned out, Eire would win just one medal at the Games, when 69-year-old Letitia Hamilton picked up a bronze medal for her painting of the Meath Hunt Point-to-Point Races in the Olympic art competition.

Still, the London Games managed to set an Olympic attendance record, and an unlikely Olympic star emerged. Fanny Blankers-Koen of Holland, 6 feet tall and 30 years old, was a “shy, towering, drably domesticated” straw-blonde mother of a 7-year-old son and a 2-year-old daughter who talked of how she liked cooking and housekeeping. She also won four gold medals in track and field and became “as well known to Olympic patrons as King George of England.” Nicknamed the “Flying Housewife,” Blankers-Koen achieved this feat while pregnant with her third child.

Born Francina Elsje Koen on April 26, 1918, in Lage Vuursche, a village in the Dutch province of Utrecht, she demonstrated remarkable athletic abilities as a young child and ultimately settled on track and field after her swim coach advised her that the Netherlands was already loaded with talent in the pools. At 17 years old, Koen began competing in track events and set a national record in the 800-meter run; a year later she qualified in the trials for the 1936 Olympics in Berlin in both the high jump and the 4 x 100 relay. She attended the Games, and although she did not medal in her events, she did manage to meet and get an autograph from her hero, the African-American track star Jesse Owens, whose record four gold medals she would later match in London. The meeting was, she would later say, her most treasured Olympic memory.

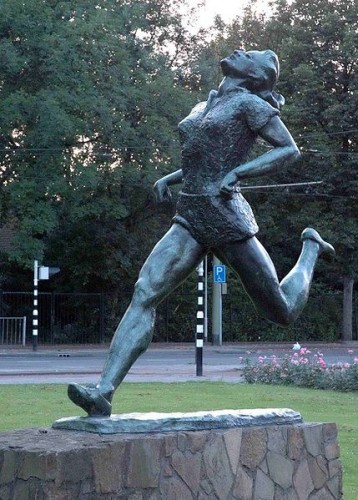

Fanny Blankers-Koen was voted female athlete of the century in 1999 by the International Association of the Athletics Federations. Photo: Nederlands Instituut voor Beeld en Geluid / NOS

Fanny was just coming into her prime as a runner when she married her coach, Jan Blankers, in 1940. She’d won European titles and set multiple world records in the 80-meter hurdles, high jump and long jump. But because of the war, the Olympics were canceled that year and again in 1944. Still, she qualified to return to the Olympics, leaving her children behind in Amsterdam. “I got very many bad letters,” she recalled, “people writing that I must stay home with my children.”

The British team manager, Jack Crump, took one look at Blankers-Koen and said she was “too old to make the grade.” Few knew it at the time, but she was already three months pregnant and training only twice a week in the summer leading up to competition.

The Games began on July 28 under a sweltering heat wave, when King George VI opened the ceremonies at Wembley Stadium before more than 80,000 people. The athletes entered the stadium, nation by nation, and toward the end of the pageant, the American team, dressed in blue coats, white hats, white slacks and striped neckties, received a tremendous and prolonged ovation for their efforts during the war. It was a moment that, one American reporter said, “provided one of the greatest thrills this reporter has had in newspaper work.”

Blankers-Koen got off to a strong start in the 100-meter sprint, blowing away the field to capture her first gold medal, but despite being favored in her next event, the 80-meter hurdles, she was slow out of the blocks, bumped a hurdle and barely held on in a photo finish to win her second gold. Feeling the pressure, she burst into tears after one of her heats in the 200-meter event, complained of homesickness, and told her husband that she wanted to withdraw.

In addition to hyping Blankers-Koen as the “Flying Housewife,” newspaper coverage of her exploits reflected the sexism of the time in other ways. One reporter wrote that she ran “like she was chasing the kids out of the pantry.” Another observed that she “fled through her trial heats as though racing to the kitchen to rescue a batch of burning biscuits.”

Her husband patiently talked to her about continuing, and Blankers-Koen reconsidered, regrouped, then set an Olympic record in the 200 meters on her way to winning her third gold medal of the Games. In her final event, she was to run the anchor leg in the 4 x 100 relay, but the Dutch team was panicked to learn, shortly before the finals, that Blankers-Koen was nowhere to be found. A shopping trip had delayed her arrival at the stadium. She finally made her way down to the muddy track in her bright orange shorts, and by the time she’d received the baton, the Dutch were in fourth place, well behind. But she came roaring toward the finish line, closed a four-meter gap and caught the lead runner to win the gold.

Despite eclipsing Babe Didrikson’s three Olympic medals at the Los Angeles Games in 1932—a performance that vaulted the American athlete into superstardom—Blankers-Koen is mostly forgotten today. As the world record holder in both the high jump and long jump at the time, it’s possible she could have added two more gold medals in 1948, but Olympic rules allowed participation in only three individual events, and the Dutchwoman chose to run rather than jump. When she returned to her country, she received not millions of dollars worth of endorsement contracts, but a new bicycle.

In 1972, she attended the Munich Games and met Jesse Owens once again. “I still have your autograph,” she told her hero. “I’m Fanny Blankers-Koen.”

“You don’t have to tell me who you are,” Owens replied. “I know everything about you.”

In 1999, she was voted female athlete of the 20th century by the International Association of Athletics Federations (Carl Lewis was voted the best male athlete). And yet Blankers-Koen was surprised. “You mean it is me who has won?” she asked. Yet despite her modesty and demure giggle, her biographer Kees Kooman portrays her as a deeply competitive athlete. Fanny Blankers-Koen died in 2004 at the age of 85.

In preparation for the 2012 Olympic Games, Transport for London created a commemorative “Olympic Legends Underground Map,” but among the more than 300 athletes listed, Fanny Blankers-Koen’s name was nowhere to be found. The agency has since acknowledged the “mistake” and promised to add her name on future printings.

Sources

Articles: “Eyes of World on Olympics,” Los Angeles Sentinel, July 29, 1948. “Seldom Seen London Sun Fells Many, Wilts Others” Washington Post, July 30, 1948. “No Food Poisoning Among Olympic Stars,” Hartford Courant, August 8 1948. “Holland’s Fanny Would Have Won 5 Titles With Help From Olympic Schedule-Makers,” Washington Post, August 8, 1948. “Dutch Woman Wind Third Olympic Title,” Chicago Tribune, August 7, 1948. “Athletics: Mums on the run: Radcliff can still rule world despite pregnant pause,” by Simon Turnbull, The Independent, October 21 2007. In 1948, “London Olympics provided different challenges,” by Bob Ryan, Boston Globe, July 27, 2012. “Fanny Blankers-Koen,” The Observer, February 3, 2002. “The 1948 London Olympics,” by Janie Hampton, August 15, 2011, http://www.totalpolitics.com/history/203762/the-1948-london-olympics.thtml

Books: Kees Kooman, Fanny Blankers-Koen: De huisvrouw die kon vliegen, De Boekenmakers, 2012.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/gilbert-king-240.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/gilbert-king-240.jpg)