The Copper King’s Precipitous Fall

Augustus Heinze dominated the copper fields of Montana, but his family’s scheming on Wall Street set off the Panic of 1907

![]()

Frederick Augustus Heinze was young, brash, charismatic and rich. He’d made millions off the copper mines of Butte, Montana, by the time he was 30, beating back every attempt by competitors to run him out of business. After turning down Standard Oil’s $15 million offer for his copper holdings, Heinze arrived in New York in 1907 with $25 million in cash, determined to join the likes of J. P. Morgan and John D. Rockefeller as a major player in the world of finance. By the end of the year, however, the Copper King would be ruined, and his scheme to corner the stock of the United Copper Co. would lead to one of the worst financial crises in American history—the Panic of 1907.

He was born in Brooklyn, New York, in 1869. His father, Otto Heinze, was a wealthy German immigrant, and young Augustus was educated in Germany before he returned to the United States to study at Columbia University’s School of Mines. An engineer by training, Heinze arrived in Montana after his father died, and with a $50,000 inheritance he developed a smelting process that enabled him to produce copper from very low-grade ore in native rock more than 1,500 feet below ground. He leased mines and worked for other mining companies until he was able, in 1895, to purchase the Rarus Mine in Butte, which proved to be one of Montana’s richest copper properties.

In a rapid ascent, Heinze established the Montana Ore Purchasing Co. and became one of the three “Copper Kings” of Butte, along with Gilded Age icons William Andrews Clark and Marcus Daly. Whip smart and devious, Heinze took advantage of the so-called apex law, a provision that allowed owners of a surface outcrop to mine it wherever it led, even if it went beneath land owned by someone else. He hired dozens of lawyers to tie up his opponents—including William Rockefeller, Standard Oil and Daly’s Anaconda Copper Mining Co.—in court, charging them with conspiracy. “Heinze Wins Again” was the headline in the New York Tribune in May of 1900, and his string of victories against the most powerful companies in America made him feel invincible.

“He has youth and magnetism upon his side,” one Montana mining engineer said at the time, “and is quite the hero of the state today. He has had laws passed that benefit every smelter and independent mine owner.… The more he is threatened, the more he laughs, and the brighter his songs and his raillery, as he entertains at the club the lawyers or the experts upon either side equally well.”

The miners in Montana adored him because he cut their working day from 10 hours to 8, and he navigated the political world with the same ease that he pulled copper from the earth. In 1902, with authorized capital of $80 million, he incorporated the United Copper Co. and continued to chip away at the position of Anaconda’s corporate successor, the Amalgamated Copper Mining Co., atop the copper market. Stock in his company was literally traded outside the New York Stock Exchange in “on the curb” trading that would later become the American Stock Exchange.

Heinze was a hard-drinking ladies man who liked to gamble, and he spent lavishly in Butte’s saloons. He was friendly with legislators and judges. (A “pretty girl” alleged to have connections to the Copper King once offered a judge a bribe of $100,000. Heinze was implicated in the attempt but never charged.) Heinze bought a suite in the Waldorf-Astoria Hotel in New York City and paid for an entourage of friends to travel with him on yearly trips. “Broadway howls when the copper crowd whirl down in their automobiles,” one newspaper reported in 1906. “Everyone in the party enjoys himself carte blanche at Mr. Heinze’s expense on these tours, and the commotion the Western visitors created last May during the annual Heinze tour furnished the newspaper with columns of good stories.”

Yet despite his charm and gentlemanly demeanor, Heinze carried a reputation as a man not to be trifled with. When some thugs from Utah arrived in Butte and tried to assault Heinze and a friend on their way home from a club, the Copper King and his friend fought their attackers off, “pounding their heads in the gutter, and a few minutes later the thugs were handed over to the police,” one miner told the Boston Globe.

“Now, what are you going to do with a man who can’t be hit with a bullet, or clubbed out, or litigated out, or legislated out, has no debts and no speculations to corral, and in absolute fearlessness can return two blows for one in every field, can make millions when copper is up and can still make money when copper is at such a price as will make unprofitable the Anaconda works as at present operated?” the miner wondered at the time. “I believe Heinze is a winner.”

In 1907, Heinze set out for New York, moved United Copper to 42 Broadway in Manhattan, and determined to prove that he could succeed in finance. Though he knew little about banking, he aligned himself with Charles W. Morse, a Wall Street speculator who controlled several large banks and owned a big piece of the Mercantile National Bank. Together, the two men served as directors of more than a dozen banks, trust companies and insurance firms.

Down the hall from Heinze at 42 Broadway, his two brothers, Otto and Arthur, had set up a brokerage firm, hoping they too could make their fortunes on Wall Street. Otto is believed to have come up with the scheme to corner the stock on United Copper by engaging in a short squeeze, where the Heinzes would quickly purchase as much United Copper stock as they could, hoping to drive up prices and leaving short sellers (who had bet the price of United Copper would drop) no one else to sell but to the Heinzes, who could then effectively name their price.

Along with Morse, the Heinzes turned to the Knickerbocker Trust Co. to finance the scheme, but the bank’s president, Charles T. Barney, believed that the short squeeze required a great deal more money, and he declined to provide it. Otto was under the impression that the Heinze family controlled the majority of United Copper’s stock, and that a vast number of the company’s shares were being sold short. He decided to go ahead with the plan anyway. On Monday, October 14, 1907, he bought United Copper shares aggressively, quickly driving the price from $39 per share to $52.

The next day, the New York Tribune ran a story headlined, “United Copper Booming,” citing a “curb market sensation” that would enable Augustus Heinze to win a bet that United Copper would surpass the price of his antagonist Amalgamated Copper.

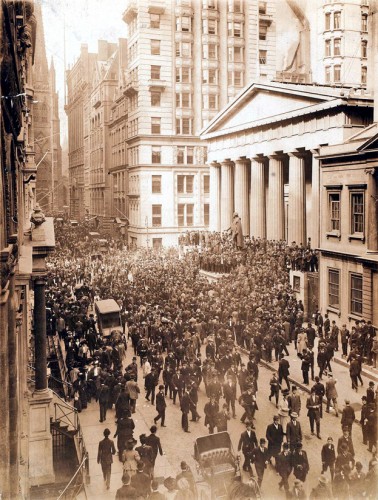

That morning, Otto issued a call for short sellers to return their “borrowed” United Copper stock, thinking he could dictate the price. But, as Barney had warned, there were more than enough United Copper stockholders to turn to, and the price began to tumble rapidly. By Wednesday, the stock had closed at $10, and the streets outside the New York Stock Exchange were calamitous. “Never has there been such wild scenes on the Curb,” the Wall Street Journal reported, “so say the oldest veterans of the outside market.”

Otto Heinze was ruined. His trading privileges were suspended, and his company was bankrupt. But the collapse of United Copper’s stock was so alarming, people began pulling their money from the banks and trusts that Augustus Heinze was associated with. The panic triggered a run on Knickerbocker Trust, the third-largest trust in New York City, forcing it to suspend operations. Barney turned to his old friend J.P. Morgan for help; after he was declined, he shot himself.

The crisis spread across the city and, soon, the nation. The Dow Jones Industrial Average plunged. The New York Clearing House demanded that Augustus Heinze and Morse resign from all of their banking interests. The Chicago Tribune published a report saying that a “young woman friend of F. Augustus Heinze” from Butte had caused the crash when she began “babbling” to friends about the corner months before, allowing “foes of Heinze” to learn of the scheme. Stock held by one such foe was “poured on the market in such volume,” the Tribune reported, “that the corner was smashed.”

J.P. Morgan did not ignore the crisis that followed. He’d rescued the U.S. Treasury once before, after railroad overbuilding and speculation had led to the Panic of 1893. Morgan quickly called a meeting of leading financiers, who pledged millions of their own funds to save failing banks, and Treasury Secretary George B. Cortelyou pledged an additional $25 million in liquidity. John D. Rockefeller deposited $10 million in one trust company, promising Morgan that he would dig deeper if necessary. For his part, Morgan purchased $30 million in New York City bonds, which prevented the city from going bankrupt. By early November, the markets began to recover.

The Panic of 1907 led to the creation of the Federal Reserve System in 1913, to give the government a mechanism for preventing banking panics. Morse and Augustus Heinze were charged with breaking banking laws in the attempted corner of United Copper stock, but while Morse was convicted, Heinze’s luck in the courts continued: He was eventually exonerated. He married an actress, Bernice Henderson, in 1910, but after the two had a son (Fritz Augustus Heinze, Jr.), they divorced in 1912.

United Copper was placed into receivership and defunct by 1913. Heinze returned to Montana poor, but a hero; his efforts on behalf of workers and independent miners had not been forgotten. He managed to recover some of his wealth with new mining projects in Idaho and Utah, but friends noted that he’d lost much of his spirit. After cirrhosis of the liver caused a stomach hemorrhage, Heinze died in November of 1914 in Saratoga, New York. He was only 44.

Sources

Articles: “Who is Heinze?” Boston Daily Globe, February 4, 1900. ”Siz New Millionaires and How They Got Their Money,” Chicago Daily Tribune, March 24. 1900. “Heinze Wins Again,” The New York Tribune, May 18, 1900. “Frederick Augustus Heinze,” Engineering and Mining Journal, Vol. 98, No. 20, November 14, 1914. “Copper Falls and Smashes Famous Heinze,” Atlanta Constitution, October 18, 1907. “Heinze Has a Hard Pounding,” Boston Globe, October 17, 1907. “Heinze Owed Fall to Babbling Girl,” Chicago Tribune, October 20, 1907. “Morse and Remorse: The Consequences of Pyramidal Banking,” Saturday Evening Post, November 30, 1907. ”Lessons from the Panic of 1907,” Ellis W. Tallman, Jon Moen, Economic Review, Federal Reserve Bank of Atlanta, May, 1990. “F. Augustus Heinze, Mine Owner, Dead,” New York Times, November 5, 1914.

Books: Robert F. Bruner and Sean D. Carr, The Panic of 1907: Lessons Learned from the Market’s Perfect Storm, John Wiley and Sons, 2007. Ron Chernow, The House of Morgan, Atlantic Monthly Press, 1990. Sarah McNelis, Copper King at War: The Biography of F. Augustis Heinze, University of Montana Press, 1968.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/gilbert-king-240.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/gilbert-king-240.jpg)