The Story of How McDonald’s First Got Its Start

From the orange groves of California, two brothers sought a fortune selling burgers

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/83/66/83668b53-6c9f-4db6-845e-a13d083acf6e/12417851_636538253151507_5379487058622609205_n.jpg)

Before southern California’s glorious, golden landscape was etched with eight-lane superhighways and tangles of concrete flyovers choreographing a continuous vehicular ballet; before families became enchanted with the thrill and convenience of popping TV dinners into the oven; before preservatives and GMOs allowed food in mass quantities to be processed, preserved and transported in refrigerated trucks and served up in disposable packaging at fast-food franchises for quick consumption on the go to harried, hungry travelers, there were oranges. Millions of oranges, fragrantly punctuating thousands of acres.

In this plentiful agricultural bounty at the dawn of the automotive age, visions of dollar signs danced in entrepreneurs’ heads. They erected giant facsimiles of the brightly colored orbs, cheerful and whimsical and visible from a distance to motorists as they bumped and bumbled their way down the open road. Inside these stands, they pressed fresh, thirst-quenching juice, a nickel a glass, to revive the overheated motorist. (For this was before air-conditioning in cars, too.)

Squeezing citrus was hardly the aspiration of two brothers named McDonald from frosty Manchester, New Hampshire. They’d watched as their father had been kicked to the curb after 42 years of employment at the G. P. Crafts shoe factory, told he was too old to be of use any more. Just like that, his working days were done. The indignity of his dismissal impressed upon his children the urgency of taking control of their own futures in order to avoid such a fate. Older brother Maurice, known as Mac, trekked west first, followed by Dick, seven years his junior, in 1926, two among the first crop of speculators to blaze the trail millions more would tread in the decades to come. Their hope was to find fame, or at least unearth fortune, in the burgeoning industry of moving pictures and to become millionaires by the time they turned 50.

To pay the rent, the brothers wound up sweating for a paycheck at Columbia Movie Studios, hauling sets and working lights during back-breaking shifts on silent film sets. Their $25-a-week salaries were hardly enough to allow them to live like kings and certainly not enough to guarantee their futures.

Unable to work their way into the more alluring behind-the-scenes ranks of the business like producing and directing, Dick and Mac scrimped and saved in order to partake in another, less glamorous part of the industry: screening them. In 1930, they purchased a theater 20 miles east of Los Angeles, in the center of a quaint, growing orange-belt burg called Glendora. Newsreels and double features turned a trip to the cinema into an all-day affair. To dissuade patrons from toting their own food to the movies, the brothers installed a snack bar in the lobby. It seemed a sure bet.

The 750-seat Mission theater was situated just down the block from City Hall, on the tree-lined thoroughfare of Foothill Boulevard. The brothers recast the venue with an optimistic new name. But the Beacon faltered during those lean years of the Depression, and the brothers were perennially behind on their bills. They even buried some silver in the backyard as a hedge against bank closures. The only person who seemed to be making any money was the proprietor of a root beer stand named Wiley’s. And so, after seven years in business, Dick and Mac sold the theater in 1937 and shifted industries from entertainment to food service.

In the next town over, Monrovia, on a decade-old thoroughfare called Route 66, they crafted some borrowed lumber into an octagonal open-air food stand and cut a deal with Sunkist to buy fallen fruit, 20 dozen oranges for a quarter. What they christened the “Airdrome” derived its name from its proximity to the Foothill Flying Field, which fancied itself “America’s Friendliest Airport.” This air traffic drew all manner of gawkers. Since the field’s sandy acreage was enlisted, on occasion, for film shoots, there was always a chance of catching a glimpse of stars like Laurel or Hardy. Fortified by spectacle, satisfied day-trippers would then sidle over to the Airdrome to sate more basic needs, their thirst and hunger, with a fresh orange drink and a hot dog. This venture was so successful that the brothers were able to import their parents from New Hampshire and open two more stands.

The brothers briefly entertained the dream of a new establishment they’d call the “Dimer,” where every menu item cost ten cents, but rejected the idea as too Depression-era. The future, they were certain, involved appealing to drivers. Soon, they believed, the work week would shrink to under four days, leaving Americans with abundant leisure time in which to tool around in their cars—and stop to eat. They dismantled their stand and ventured farther east, to the growing desert city of San Bernandino, or San Berdoo as locals called it, a long-established trading hub 60 miles outside of Los Angeles. Their optimism about the future buoyed them through rejections from bank after bank, until they finally managed to talk their way into a $5,000 loan from a lender wowed by the location they’d chosen in downtown San Berdoo at E Street and 14th. The only collateral the brothers possessed besides their dreams was their tired old octagonal juice stand, which they had spent $200 on a mover to slice in half and move to its new home. This time, the entrepreneurs plastered their surname on their reincarnated establishment, followed by the featured menu item: “McDonald’s Barbeque.”

Like other roadside restaurants of its day, McDonald’s Barbeque offered food delivered direct to the customer’s car via a fleet of attractive young women called carhops, so named because of their practice of jumping up on the auto’s running board to claim a patron as their own. Ever thrifty, Dick and Mac outfitted these ladies in usherette uniforms recycled from the Beacon, embellishing the already theatrical flourish of service to your window.

McDonald’s survived the challenging depravity of the war years, when creature comforts and pleasures were duly rationed. The declaration of armistice allowed the curtain to rise on an era of playful abandon, which suddenly swept over the most banal aspects of life. Americans had been banking both their money and their desire for fun, and now they were making up for lost time. Henry Ford’s production lines began turning out cars after the wartime halt, vehicles priced for the average consumer. By 1950, 40 million cars jammed the roads. Taxes collected on fuel sales allowed the construction of wide new thoroughfares offering access to large swaths of America and new possibilities for adventures. All this meant a need for expanded services: gas stations and restaurants and motels. The journey became as critical as the destination. Eating meals outside the home became not just socially acceptable but a sign of carefree affluence. Eating a meal delivered directly to the window of your beloved new vehicle punctuated the feeling car ownership allowed.

Roads that had once been thick with orange groves were now dotted with quick-serve restaurants. While once a mound of ground beef was considered to be a tasteless and suspect blob of glop, suddenly the hamburger was de rigueur. But to the consternation of the family-minded, food wasn’t all that could be had at these stands. Drive-ins became minefields of unsavory behavior, filled with loitering teenagers who smoked and blasted the jukebox and engaged in sexual shenanigans in the parking lot with the hired help. Staff seemed to churn through a revolving door; employees would quit or no-show, regularly leaving their employers in the lurch.

None of this served to diminish sales. A steady flow of customers kept a cast of 20 carhops hopping and the parking lot, with room for 125 vehicles, brimmed to capacity, the go-to place in town for the younger set. In the face of this success, in 1948, Dick and Mac made the bold, perhaps foolish, decision to step back and reassess, closing their doors for a hiatus. Dick and Mac asked themselves how they could prepare hamburgers, fries and shakes as efficiently as possible. How, they wondered, could they streamline operations for maximum profit? How could they distinguish themselves from the other drive-ins? How could they speed up service?

In their quest for answers, they drew inspiration from East Coasters named Levitt. This enterprising family applied Ford’s Model T–like assembly-line logic to building homes on New York’s Long Island, where housing was needed in abundance to fill the rapidly expanding suburbs. The McDonald brothers’ goal was to mimic this prefab mentality in the preparation and serving of food: “Levittown on a bun.”

To begin with, the brothers analyzed their business receipts to identify the best sellers, and slashed their menu from twenty-five items to the nine most popular items, nixing the pricey and labor-intensive barbeque. Dick deviously posed as a freelance writer and ventured into Los Angeles to sleuth out trade secrets from the candy industry. In a hand-operated confectioner’s cone used to form peppermint patties, he found inspiration. Dick enlisted a mechanically minded friend to fashion an automatic condiment dispenser that doled out a precise squirt of ketchup or mustard at the push of a button. A mechanized press allowed for the quick formation of beef into patties. To keep up with demand for milk shakes, Dick and Mac purchased eight state-of-the-art blenders called Multimixers, which allowed them to churn out frothy drinks—five at a time per machine. Surplus could be stored in the fridge, ready for the asking. Crucially, in the brothers’ new business model, the customer was not allowed to request substitutions. Offering choice, the brothers said, dashed the speed.

To execute the next phase of their makeover, they retreated, in the dark of night, to the tennis court behind their home. Using thick chunks of red chalk to plot the action, they choreographed an assembly line of food preparation and delivery, where workers could most efficiently grill the meats (40 patties in 110 seconds), fry the fries (900 servings an hour), and dispatch an entire meal to a hungry customer in just 20 seconds. After they’d called it quits, a rare desert rainstorm struck, washing away the marks they’d charted out. Nonplussed, the next day the stoic brothers plotted it out all over again.

This hamburger dance allowed Dick and Mac to address the costly issue of personnel. The alluring carhops were swiftly marched out of the picture: Customers would have to get out of their cars and—gasp—walk to the window to order. And while they were there, they could gaze inside the “fishbowl,” and marvel at the meticulous, efficient kitchen where their food was being prepared. The new staff was to be all male, outfitted in tidy, conservative paper hats and white uniforms which imbued them with an air of surgical cleanliness and precision. Women employees, the brothers believed, presented an unnecessary distraction.

The pièce de résistance of the reincarnated operation was the price list. Factoring in the lower labor costs, the brothers could now charge crucial pennies less than the competition. Fifteen cents for a burger, ten cents for a bag of fries, and twenty cents for a creamy, triple-thick milk shake. Dick and Mac were counting on the math of their reduced operational costs, plus a high volume of sales, to add up to a handsome profit.

Customers roundly despised it. Some drove into the lot, only to peel off when no carhop appeared. Others lamented the loss of the old, longer menu and the inability to customize. The brothers took to having employees park in front of the restaurant, so the place didn’t look so dead. All to no avail. The facelift was a disaster.

Four months in, a miraculous turnaround occurred, for no particular reason. Cabbies came, then construction workers, then kids, and, soon, lines of hungry customers began to crowd the counter, and the presence of those customers attracted others. Sales were so brisk the brothers commissioned a painting of a rising thermometer in the front window, a neat visual to boast the sales. When the number reached a million, Dick said, the painter would add an explosion to the top. Profits soon soared to a bounteous $100,000 a year, which allowed them to partake in their own personal automotive fantasy, upgrading to the newest Cadillacs on the market—three of them, including one for Mac’s wife. (Dick had yet to marry.)

Hamburger seekers, it seemed, were indeed willing to trade choice for speed and price. The quality of the food wasn’t the main draw. The exception, perhaps, was the brothers’ fries, the paragon of crispy freshness. Mac had become a wizard of the spud, applying principles of chemistry and perfecting a recipe through painstaking trial and error. The magic step involved drying Idaho russets in the desert air to break down the sugar content, a crucial if time-consuming step. Patience was as virtuous as precision: Improperly blanching, or in any way trying to hasten the process, was sure to yield greasy, limp potatoes, the sort fried up by the competition. It was the one arena in McDonald’s recast formula in which slow and deliberate were essential and allowable ingredients.

Aside from the long lines, the brothers had another indication that they had a hit on their hands. Would-be imitators arrived to study the operational ballet on display behind the store’s glass windows. When these copycats pressed for details on what they couldn’t see, Dick and Mac cheerily shared trade secrets. Eventually, it dawned on them that they could put a price tag on their formula and pocket some extra cash. In 1952, a few months after their shortening provider, Primex, ran a piece in the trade journal American Restaurant lauding the prolific French fry operation at McDonald’s, the brothers took out an advertisement themselves. They promised readers “The Most Important Sixty Seconds in Your Entire Life.”

At the ad’s centerpiece was a picture of their unique hexagonal building, glowing. Their “revolutionary development in the restaurant industry” was now available for sale to interested parties. A cover story echoed the hype, trumpeting McDonald’s sales of “one million hamburgers and 160 tons of French fries a year” and revealing a whopping gross annual take of $277,000. That cinched it. For aspiring hamburger barons, San Berdoo became Oz.

The more honest in the bunch plunked down a $950 franchise fee for the formula, instead of just paying a visit and stealing the idea. First in line was an oil executive from Phoenix named Neil Fox whose family considered him nuts for jumping into this déclassé hamburger racket. Dick and Mac thought Fox was nuts, too—for wanting to use their name on the stand he intended to build, and not his own. The word “McDonald’s” meant nothing outside San Bernardino, they said. Fox explained to the brothers that he thought their name “lucky.”

Besides the name, for his money Fox got an operating manual, a counterman on loan for a week to show him the ropes, and, capping off the brothers’ reimagination of the drive-in, a hot-off-the-press architectural blueprint from which to build a specially designed red-and-white tiled restaurant—suitably eye-catching and accommodating of the sacred automobile. Dick, the younger and more marketing savvy of the pair, was insistent about his vision: He imagined a pair of parabolas hoisting up the structure. A growing backlash against the scourge of billboards lining new roads was forcing designers to fashion the structures themselves as signs. Bold, even wild, designs were sweeping the roads, becoming standard markers for roadside joints and restaurants, the better to grab the eye of motorists and punctuate the landscape with soaring roofs, boomerangs, and starbursts shooting kaleidoscopes of colors.

One prospective architect balked and tried to talk the brothers out of the idea of arches; another complained about being told what to do and suggested the arches were so harebrained that Dick must have cooked them up during a nightmare. At last, in Stanley Meston, the McDonald brothers found an accomplice. Meston sketched out a 12-by-16-foot red-and-white-tiled workspace, easily approachable by and visible to customers. As instructed, he attached neon-trimmed golden arches to this structure, rising from the side of the building like rainbows, which made the building look as if it were ready for lift-off. The building itself now functioned as a sign—all the better to catch the roving eye of motorists.

Hundreds of inquiries streamed in. The dairy supplier Carnation was eager to swoop McDonald’s and its winning formula into its corporate fold. Hoping to encourage sales of ice cream, the company’s brass tendered an offer to replicate McDonald’s nationwide. The brothers considered the alliance and ultimately refused; they were happy with the status quo and disinclined to have their enterprise and their personal lives enveloped by a large bureaucracy. The extra work hardly seemed worth the potential payoff. “More places, more problems,” lamented Mac. “We are going to be on the road all the time, in motels, looking for locations, finding managers.” It was easier just to sell the manual and blueprints and to pocket the $950 fee.

One day, among the steady stream of curious looky-loos on E Street was a compact, well-dressed, hard-up 52-year-old salesman from Chicago, on the hunt for a lucky break. His name was Ray Kroc.

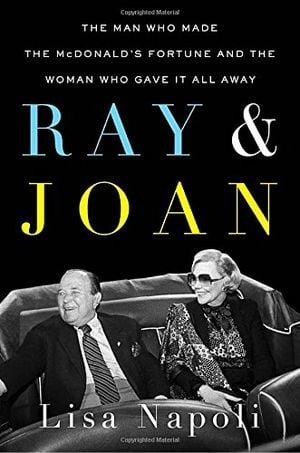

From RAY & JOAN: The Man Who Made the McDonald’s Fortune and the Woman Who Gave It All Away by Lisa Napoli, published on November 15, 2016 by Dutton, an imprint of Penguin Publishing Group, a division of Penguin Random House LLC. Copyright © 2016 by Lisa Napoli.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Lisa-Napoli.jpeg)