The Inside Story of Baseball’s Grand World Tour of 1914

As the 2014 season opens in Australia, they are really only following in the footsteps of the Giants and the White Sox from 100 years ago

:focal(479x137:480x138)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/5d/ef/5defcc8c-3afa-4b8f-b3b3-92392a19ffcc/tours_1913-1914_969-83_pd1.jpg)

The 2014 baseball season opens this weekend when the Los Angeles Dodgers and the Arizona Diamondbacks play two regular-season games in Sydney, Australia, more than a week before the rest of the teams officially hit the field. Certainly Major League Baseball hopes to illustrate the global popularity of American baseball – but it’s been done bigger and better before. A century ago, an international tour yet to be equaled featured the New York Giants, Chicago White Sox, and Jim Thorpe, the man considered the greatest athlete on the planet who was simply glad to have a job.

The instigators of the around-the-world series of games were John “Mugsy” McGraw of the Giants, the most successful manager in baseball, and Charles Comiskey, owner of the White Sox. One night in December 1913, McGraw and Comiskey were having drinks at “Smiley” Mike Corbett’s bar on Chicago’s East Side, and the idea of a world tour came up. McGraw knew something about the business – he was in the midst of a 16-week tour of vaudeville theaters, where all he had to do was tell baseball yarns for a whopping $3,000 a week. Comiskey was already rich and McGraw was getting there, so making money was not the main motive for a journey around the globe. Both men were envious of the fame that Albert Spalding, seeking to spread the reach of his sporting goods company, had achieved when he had led players on an 1889-90 tour of several countries including New Zealand, Australia, Egypt and Italy. McGraw and Comiskey wanted to lead a bigger and better tour with teams representing the two biggest cities in the United States. The 25th anniversary of Spalding’s adventure was approaching, so the time was right for a new edition.

The tour that McGraw and Comiskey envisioned would begin as a barnstorming trek across the country right after the 1913 World Series. Upon reaching the West Coast, the two teams and whoever else was allowed to tag along (especially reporters) would board a ship to take them across the Pacific. The tour’s first stop on foreign soil would be in Tokyo and, going from east to west, the last one would be in London. In between the travelers would touch down in China, the Philippines, Egypt, Ceylon, France, and other countries with at least a rudimentary ballfield.

McGraw and Comiskey filled out most of the roster of current Giants and White Sox played, but they cast a wider net for a few famous and more colorful players. On board were future Hall of Famers Christy Mathewson, Tris Speaker, Urban Farber and “Wahoo” Sam Crawford. Among those joining them were James “Death Valley Jim” Scott, George “Hooks” Wiltse, “Bunny” Hearn, “Turkey” Mike Donlin, and others who nicknames matched their personalities.

The most famous of them all was Jim Thorpe. Regarded as the greatest athlete at the 1912 Summer Olympics in Stockholm, by 1913 he was also the world’s most notorious one. That January, the Worcester Telegram reported that a few years earlier Thorpe had earned $2 a game playing professional baseball in the Eastern Carolina League. The ensuing headlines prompted the Amateur Athletic Union to begin disciplinary proceedings that would result in Thorpe being stripped of his medals. Newly married and needing to make a living, Thorpe jumped at the New York Giants’ offer of a three-year deal that would pay him a $6000 annually, when most players in 1913 took home $2000 or less.

At the end of the season, the Giants, boasting a 101-51 record and dominating the National League, faced the Philadelphia Athletics in the 1913 World Series. McGraw had visions in his head of rounding the world as the world champion manager, but the Athletics took the championship in five games. The last loss, 3-1, was especially galling for McGraw because of what the New York Times reported as “witless blunders” by his team and being shut down by Old Man Plank, at 40 years old, the oldest pitcher in baseball.

The Giants, however, were still the marquee name in baseball. (The White Sox, at 78-74, had finished fifth in the American League.) The much-anticipated tour finally got underway on October 18 with an 11-2 Giants victory in Cincinnati, just one week after the end of the World Series.

What piece of the profits would the players get? None. According to James E. Elfers, author of the definitive account The Tour to End All Tours, the players had to actually pay to participate. Elfers writes:

"They had to put up a few hundred dollars to reserve their spot on the tour. Once they boarded the Empress of Japan the players got their reserve back plus a matching amount for the tour -- they had to put up $250 and got back $500. The money the tour made around the world -- and it was considerable -- was divided three ways after expenses were met. Comiskey, McGraw, and [Comiskey crony and promoter Jimmy “Nixie”] Callahan got all the profits. I'm sure the players thought that the trip itself was perk and profit enough, but the loser’s share of the annual Chicago city series, which involved some of the tour players, was larger than the money they got for risking life and limb around the world."

After Cincinnati, the teams rode the rails through the heartland of America, with stops for games in places like Peoria, Springfield, Tulsa, Sioux City and El Paso, then on to the West Coast, where they worked their way up from San Diego to Seattle. Given that at the time the farthest-west major league franchise was the St. Louis Cardinals (which had lost 99 games in the 1913 season), the crowds on the coast were especially welcoming. The Los Angeles Times reported about the November 8 game, “A vast number of persons were found lined up fighting desperately to separate themselves from their money. The game was held until all of them succeeded in doing this that none might be disappointed.”

On December 9, the Giants boarded the Empress of Japan and set sail to visit 13 nations and travel over 30,000 miles, mostly by water and rail, decades before deep-pocketed owners sprang for private planes. The notoriously thrifty Comiskey provided most of the $90,000 for chartered steamships and brought with him a $121,000 letter of credit for additional travel expenses. (Comiskey was also a notoriously savvy businessman, and he would enjoy an excellent return on his investment.) For their part, the players, many of who had never been out of the U.S. before, knew this was their only opportunity to see the world, and why not do it on Comiskey’s dime while missing the New York and Chicago winter.

The western Pacific and subcontinent countries fascinated the players – once they got there. On the way to Japan they encountered a late-season typhoon which tossed 60-foot waves at the ship, and they were especially glad to reach Tokyo, where 5,000 Japanese fans attended the first game, 7,000 the second, both held in tiny stadiums. “Space was at such a premium that many of the fans sat on bamboo mats crammed into any open plot of land,” Elfers writes. “To the Americans, it was all very heady and overpowering.” Then for the teams it was on to China.

Thorpe proved especially appealing at the gate. To the foreign fans he was still the world’s greatest athlete, and he was touted as such in advertisements and newspaper reports anticipating the arrival of the teams. And few were aware that in the 1913 season, he had appeared in only 19 games for the Giants and batted an anemic .143. The more romantic fans were thrilled that this was a honeymoon trip too, as Ina Thorpe was accompanying her husband on the tour. As the teams’ steamship approached the dock in Shanghai, the waiting throng chanted, “Thorpe! Thorpe! Thorpe!” The great baseball players with him were viewed as merely members of the king’s court.

After a stop in Hong Kong – where doctors had to certify that none of the visitors had smallpox -- the travelers arrived in Manila. In a ghostwritten account published in the New York Times, John McGraw reported:

In my baseball days I have been through many exciting incidents that have given me real thrills, but I never before had such a thrill as crept up and down my spine when the party of the world’s tourists arrived here yesterday.

They were greeted by wildly cheering people. Many of the Filipinos had never seen a baseball game before and perhaps didn’t know why they were cheering, but there were also many American military personnel on hand and later at the ballpark.

The new year found the teams in Brisbane, Australia. A disoriented Sam Crawford, accustomed to cold weather in January, commented, “It’s a beautiful town, if only it would snow once in a while.” One game was played there, then travel troubles jinxed them: After two games in Sydney, on January 9, where the Morning Herald reported, “If the appreciation and warmth of the greeting to the visitors by the expectant crowd of over 10,000 persons at the Sydney Cricket Ground counts for anything, the visitors need have no fears of success of their colorful adventure.” Even McGraw had been moved to shout to the crowd, “I love Australians!”

From Sydney, the teams boarded a train in Melbourne to Adelaide, but delays turned the trip into an 18-hour slog. The game there had to be cancelled so the teams could hop on the HMS Orontes for India, prompting the Adelaide Advertiser to headline an article, “Discourteous Visitors; Local Baseballers Snubbed.”

A long journey by ship, which included crossing the equator on January 20, brought the teams to Ceylon, where tea magnate Sir Thomas Lipton greeted them, and the game was played at the Victoria Gardens Racetrack before a bemused audience that wondered why they weren’t watching a cricket match. On January 23, the troupe headed for the Middle East.

Two games in Cairo opened February. For the players, more exciting than the games themselves was visiting the Pyramids and especially the Great Sphinx. With the latter, what made the visit special was watching Ivy Wingo, the Giants catcher, from 100 yards away throw a baseball over the Sphinx to where it was caught on the other side by Sox outfielder Steve Evans. Then the tourists boarded the German liner Prinz Heinrich, bound for Naples. After three days in Rome, where the travelers met Pope Pius X, they went to Nice then on to Paris. Rain washed out the games there, but undaunted, McGraw, Comiskey, and the players went sight-seeing.

England was the last stop, where in front of 20,000 spectators who included King George V, the Sox defeated the Giants 5-4 in 11 innings. When McGraw and Comiskey were presented to the king, who wore a black derby and dark suit and had never attended a sporting event at Chelsea Stadium before, they gave him three cheers and then accepted a ball from him to get the game started. After the game, King George had a message sent: “Tell Mr. McGraw and Mr. Comiskey that I have enjoyed the game enormously.”

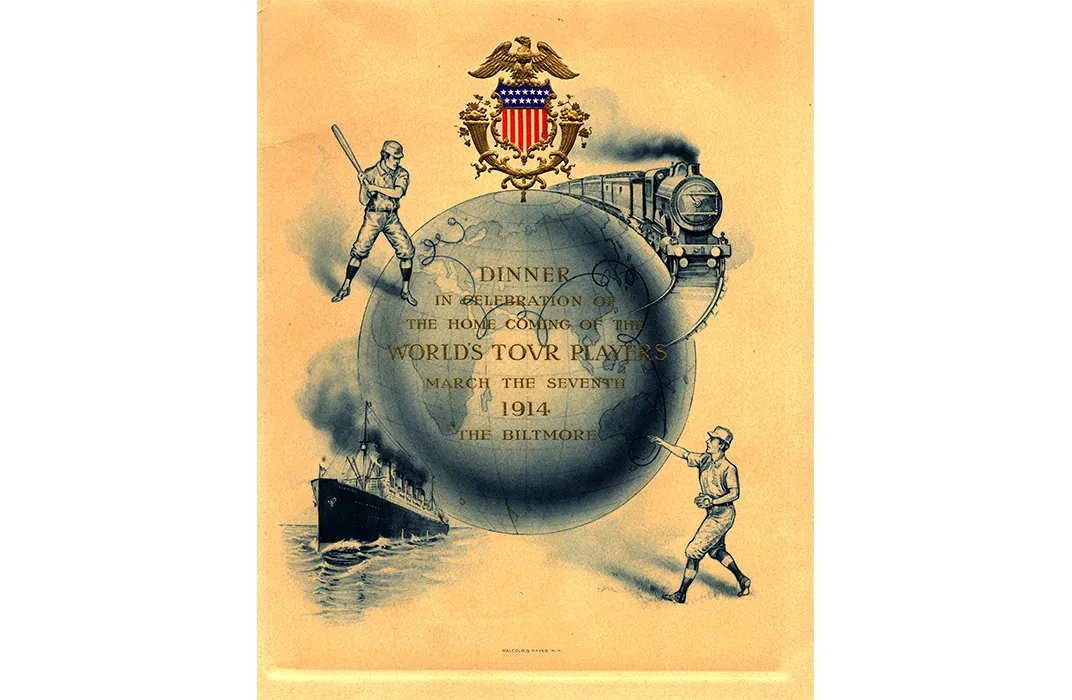

Finally, on February 28, it was time for the weary travelers to head home. They would do so in style – they boarded the Lusitania, the luxury liner that would be sunk by German torpedoes the following year killing 1198 passengers. A banquet welcoming the journeymen home was held in New York on March 7, and Comiskey hosted a second one three days later in Chicago.

Did the players finally get to go home? No, because spring training had already begun. No doubt hung over from the successful yet exhausting tour, the New York Giants finished the 1914 season 10.5 games out of first place. The White Sox fared worse, at 70-84 tying the newly-named New York Yankees for sixth place, 30 games behind the Athletics. Still, as McGraw had “written” after that last game in London, “The game was a fitting close for the great tour, which has been successful in every feature. The most notable thing to me about the whole trip was the expression of national good feeling at all points we visited.”