NATIONAL MUSEUM OF NATURAL HISTORY

New Exhibit Reveals Indians Everywhere…Except in Your Textbooks

Gwyneira Isaac, the National Museum of Natural History’s Curator of North American Ethnology, reviews the newest exhibit on display at the National Museum of the American Indian.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/blogging/featured/Americans-93.jpg)

If there was any incident that determined who I am as an anthropologist and curator, it was the moment I realized the depth of neglect in my education about Native American history.

Thirty years ago, as an intern for a filmmaker, I was sent to the basement of a library to look for government reports from the Bureau of Indian Affairs. I was astounded, not by the vast array of documents, but by the realization that—prior to this moment—I had been entirely denied access to this submerged history. This moment was transformative.

Since then, I have devoted myself to finding out anything I can about Native American and U.S. history—a journey that took me to graduate school to study anthropology and, ultimately, to the Smithsonian’s National Museum of Natural History, where I am the Curator of North American Ethnology in the Department of Anthropology. Along with fieldwork, I now also conduct research in the National Anthropological Archives which houses an array of Native American records.

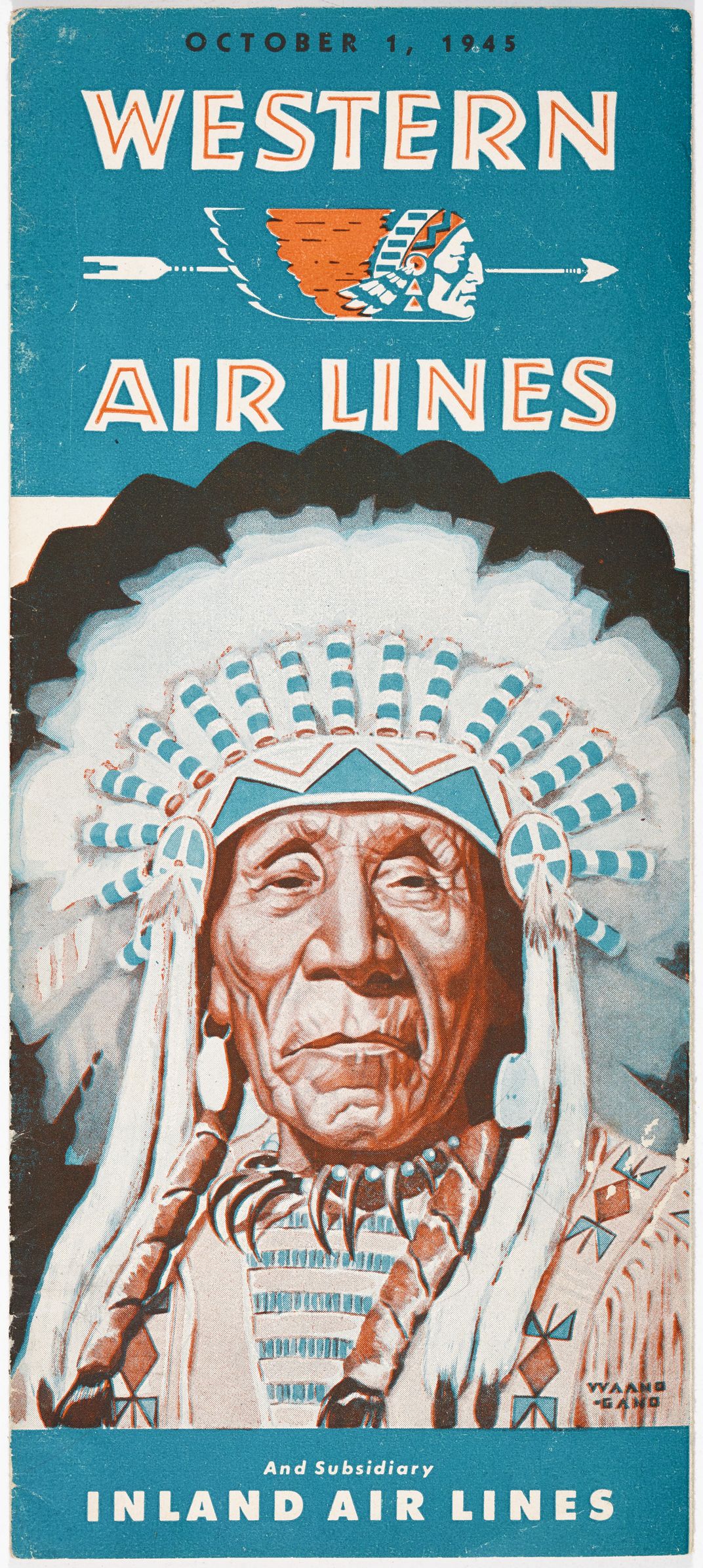

In the early years of my self-education project, I immersed myself in 19th century photographs, reports and papers that gave first-hand accounts of what it was like to be a part of Native American communities across the U.S.—faces and voices that had been denied entry into my school books. Yet, for all the stacks of government records, photos and Native American objects housed in archives and museums, the images of Native Americans that circulated on the surface in popular culture and mainstream life, year-after-year, were cartoonish stereotypes—Disney characters, sports teams’ mascots, cigar store Indians—you get the picture. What was I to make of a world in which we carefully collect, file, catalogue and care for Native American heritage in museums, and another where we decorate theme parks with Indian princesses, dream catchers and play house teepees?

Making sense of these extremes is the goal of the new exhibit, Americans, on view at the Smithsonian’s National Museum of the American Indian. The exhibit tackles how stereotypes of Native Americans mask and, at the same time, reveal hidden histories central to our national character. Through a unique display of consumer products old and new that depict Native Americans, and three carefully unpacked, well-known histories—Pocahontas, the Trail of Tears and the Battle of the Little Big Horn—the exhibit asks us to question not only what we think we know about Native Americans, but also how we know this history. How was this history created and through what myths and which types of media was it distributed?

The mechanics of history are not easy to take on. This is because they are also about the politics of history. Americans draws on the history of media to show that well-known myths—or retellings of pivotal Native American events—are not just stories as they often influence policy. For example, as part of the ways in which the history of Pocahontas plays out in modern times, the exhibit demonstrates that the state of Virginia passed the Racial Integrity Act of 1924 which divided society into “whites” and “coloreds”. Part of this Act was the “Pocahontas Exception” rule that allowed aristocratic Virginians to still claim “Indian blood” from Pocahontas, but not be classified as “colored.”

The exhibit also exposes how much of what we know about Indians is the result of the industrial age of mass production technology. In a quiet, almost hidden, area at the back of the gallery is a section labeled “the making of a stereotype.” It explains that the term “stereotype” originally referred to a metal plate used to mass-produce printed images and text. Additionally, the term “cliché” described the sound of “molten metal hitting a stereotype printing mold.” There is no coincidence in the use of terminology here. In the same way my understanding of Native American history was lacking, so too was my knowledge of the origins of this all too familiar language.

Americans reveals to you how history is never a forgone conclusion. We do not know, at any given time, how it will end or how the story will be told or retold. But we do know that those who shape the telling of the story determine who is in the picture and who gets to see or hold onto the records. This is where museums, archives and libraries come in to the story—again. Through artifacts, images, and texts, repositories like the Smithsonian offer us the privilege of revisiting the primary sources of history.

Americans brings stereotypes, myths and original documents and artifacts into the public view and encourages a conversation about the role of Native Americans in shaping America as a nation. It is a conversation that I hope will invite many others to embark on their own journey of education about Native Americans as it did for me.

The Smithsonian's National Museum of the American Indian recently launched Native Knowledge 360° an ambitious project to address the alarming lack of Native American history in the nation’s classrooms. NK360° provides essential understandings about American Indians that serve as a framework for teaching Native American history in K-12 grades. It offers teachers training and online classroom lessons based on accurate and comprehensive Native American history designed to meet national and state curricula standards.