These Sculptures of Giant Tomatoes Are Ripe For the Picking

What physical traits do humans find desirable? Artist Jessica Rath looks in her grocery store’s produce section for answers

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/6d/5a/6d5a02fe-80d4-466f-8ce3-bb8cafc03c2f/paragon.jpeg)

Restaurants and grocery stores often steal camera people from the porn industry. That's because these photographers understand how to shoot close-ups of food to seduce consumers into buying it.

Jessica Rath is fascinated by all the visuals that have been highly constructed in the produce section alone. "They are about a human desire over anything else," she says. "The shapes and colors of these fruits have very little to do with the original fruit that was found by humans and had begun to be harvested."

In her body of work, the Los Angeles-based artist considers how humans, and especially Americans, have tampered with agriculture and shaped products to their liking. She has looked at apples, visiting the U.S. Department of Agriculture's Plant Genetic Resources Unit at Cornell University, where living trees of some of the rarest and most endangered apple varieties are preserved. For her project, Take me to the apple breeder, she created porcelain apples of different builds and blushes to explore what constitutes beauty in the eyes of scientists, who graft certain trees for hundreds of years to produce the same fruit.

Now, Rath has turned to tomatoes.

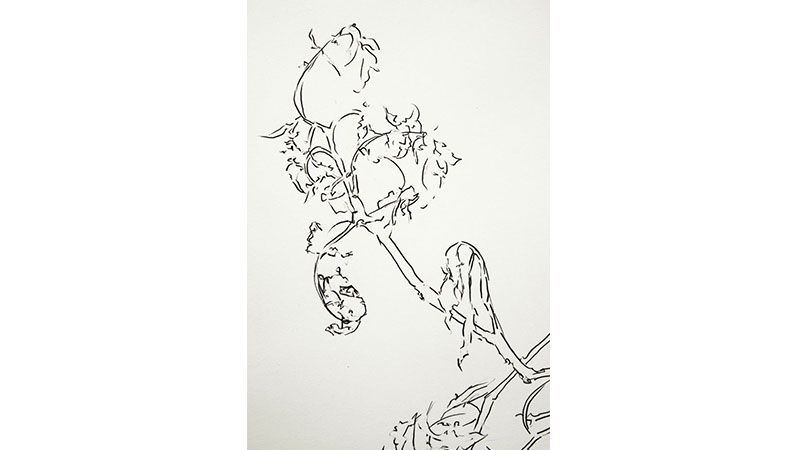

She collects roma and paragon tomatoes from her local grocery store, then draws and sculpts them from life. Unlike with her apples, which were life-size, Rath adjusts the scale of her tomatoes, for instance, forming slab clay into 18-inch-tall romas.

"Once you get them up quite large, even though they are accurate in terms of their shape, they start to become extremely abstract," she says. The artist displays the red tomatoes against the backdrop of a white gallery space, pulling them even more out of context. She hopes to draw viewers' attention to every bulge, curve and dimple, so that they might contemplate the aesthetic decisions that go into these features.

Romas, for example, were created in the 1950s, and derive at least in part from an Italian plum tomato. Growers tweaked the long plum to produce the shorter roma, Rath explains, making it cleaner looking and easier to fit into a can.

Rath also uses scale to accentuate the details of the tomatoes that are overtly anthropomorphic. "When you make them 18 inches tall, you start to have curves in them that are the same scales as a body curve, like the curve of your belly," says the artist. In this way, she exploits her viewers' notions of beauty.

Over the course of six months, Rath worked with a group of fine art finishers to develop a paint layering process that would accurately capture the complexities of "tomato red." Based on a Ferrari finish, the laquer consists of a yellow undercoat, four to six layers of red, a red that is suspended in a gloss urethane and a final layer that takes down some of the shine, giving the sculptures a bit of texture.

"Even within the uniformity of something like a beefsteak tomato, there are subtle shifts in the red," says Rath. "You see a little bit of flesh under the skin, you might see a little luminosity or you might see a bit of yellow or orange poking through. I wanted a commercial finish, but one done so tightly that I could actually insert variation that would keep your eye interested."

The seed for Rath's project was the discovery, published in the journal Science in June 2012, that the same genetic mutation that gave tomatoes a desirable scarlet color was also responsible for dulling their flavor.

"So as they had been pushing the red, the taste of the tomato had been worsening," Rath explains. "I just thought it was a brilliant metaphor for agriculture. What is tasteful to us? What is visually tasteful, and what is physically tasteful to our tongue and our mouth?"

To further inspire and inform her work, Rath read Barry Estabrook's 2011 book, Tomatoland. The book's subtitle delivers a harsh indictment: "How Modern Industrial Agriculture Destroyed Our Most Alluring Fruit."

As is typical of Rath's work, she explored the theme in multiple media. In addition to her larger-than-life sculptures of tomatoes, she produced a drawing, prints and short films—all part of a series she calls Ripe.

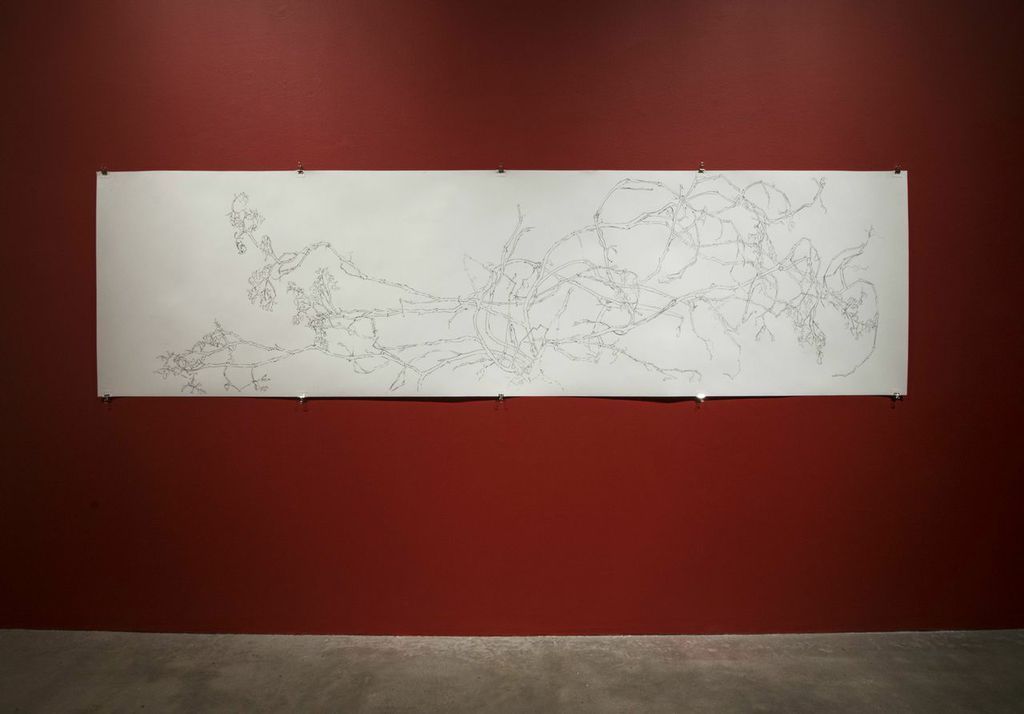

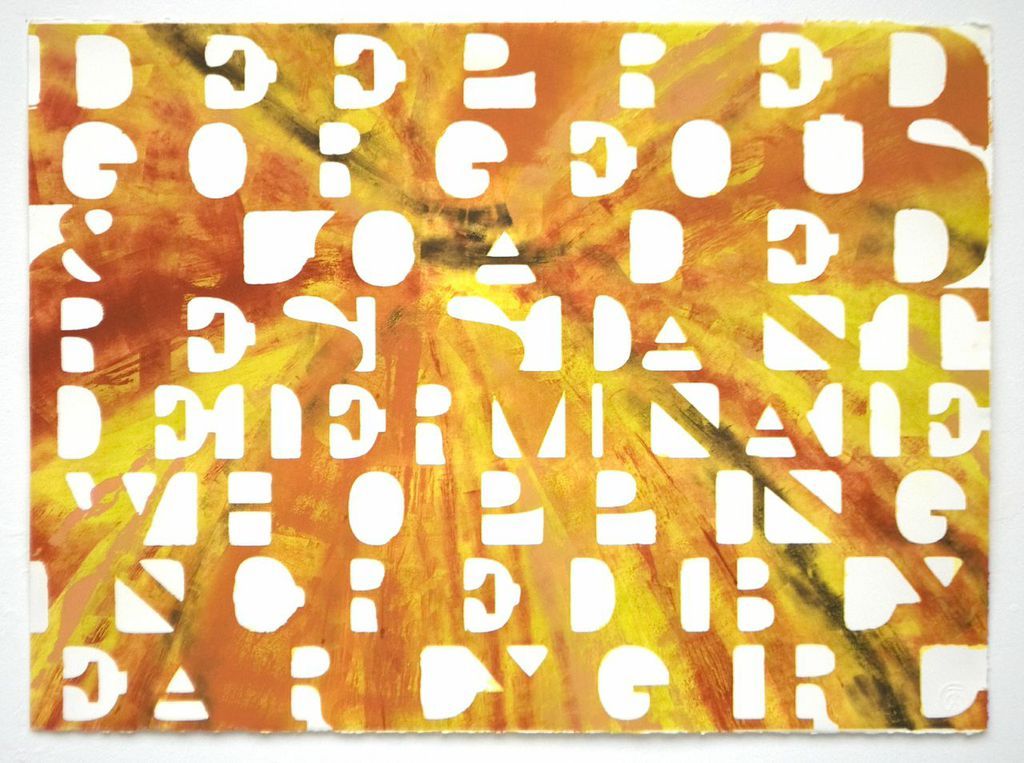

Rath documented a tomato vine that she grew and cared for over the course of 18 months in a drawing called Indeterminate (Before human). The piece consists of a drawing from life of her vine, and then a traced version of that original drawing. Together, the vines reference the plant she grew and the original tomato plant that humans found in the Andes. In a series of lithographs called Early Girl, she overlaid text from a 1970s-era Burpee Seed Catalog, something she remembers drooling over in the cold, gray winters of her childhood in southern Missouri, on a background of the varigated reds, oranges and yellows of heirloom tomatoes.

With help from a production team, the artist also created two short films. One shows tomatoes bouncing in slow motion on a trampoline. Called Ripe Gambol, this film is "a parody of 'The Man Show' segment featuring bikini-clad women," according to the Los Angeles Daily News. It is meant to be projected 14 feet wide, its score booming from two 50-inch subwoofers and a pair of 1100-watt speakers.

"You are sort of moved through the film with the music and into a level of abstraction where you no longer see them as tomatoes. You just see them as these beautiful bodies moving," says Rath. "Some of my ideas are about a kind of sexual repression that we have in this country that comes out in the strangest places."

Like the produce section of the grocery store.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/megan.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/megan.png)