When Curious George Made a Daring Escape From the Nazis

The authors of the children’s book series fled wartime France with the manuscript tied to their bikes

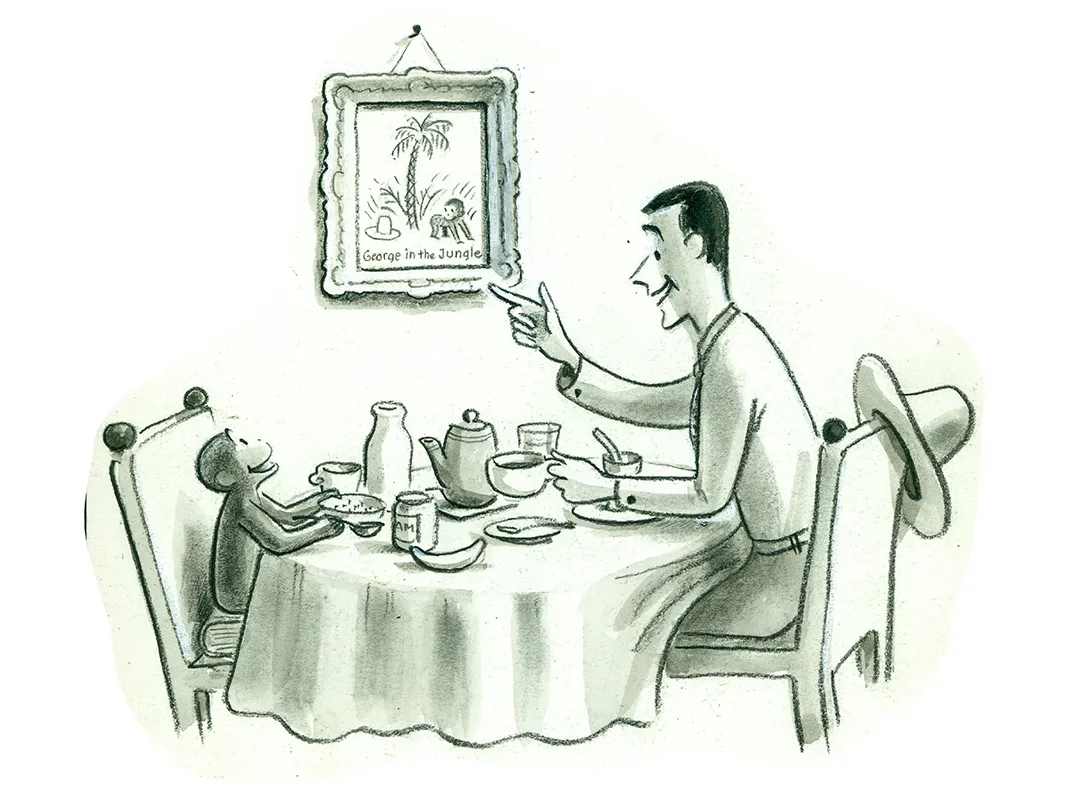

Practical, unflappable, loving, forgiving, patient—the Man in the Yellow Hat is who we would all like to be. Curious George is who we are. Well-meaning and disastrous, impulsive and forgetful, selfish and ingenious and in constant need of forgiveness. He may be the most human character in postwar literature.

And he arrived with nothing, a refugee, to became a worldwide sensation—the ultimate American story, one worth remembering on the 75th anniversary of the publication of Curious George and with an upcoming documentary about his irrepressible creators.

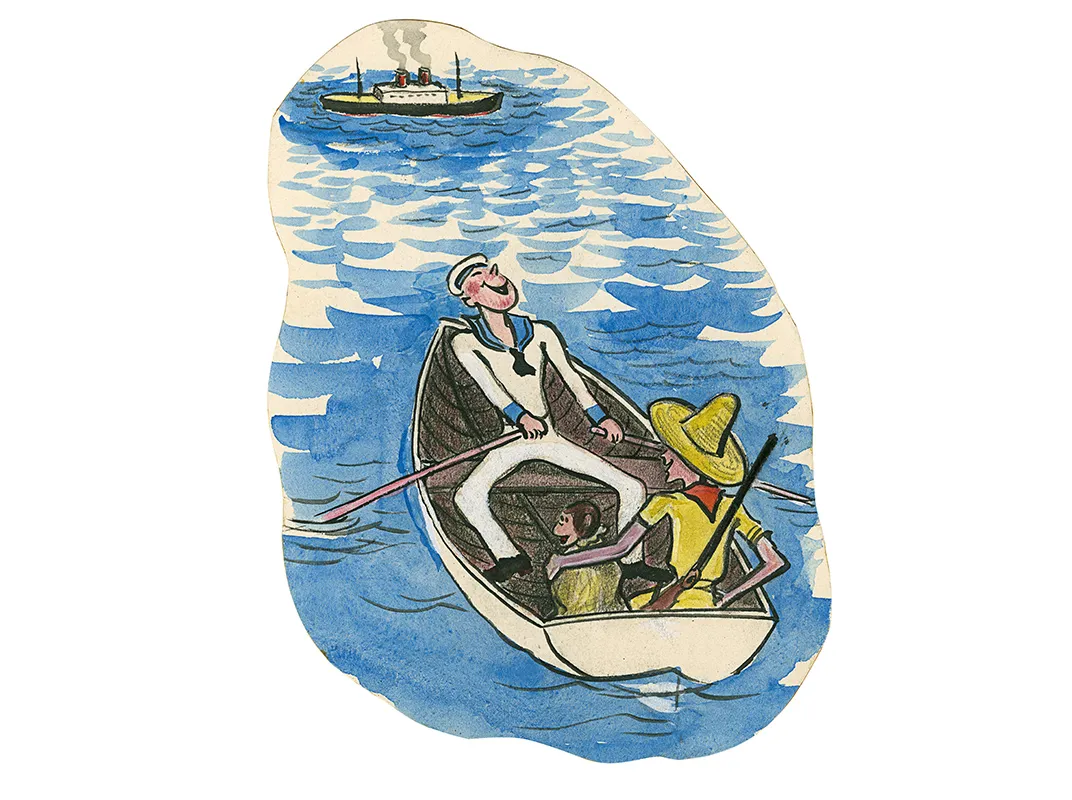

On May 10, 1940, Adolf Hitler sent three million troops through the Low Countries into France. Parisians fled by the hundreds of thousands before the Germans captured their city on June 14. Among them a young couple, German Jews who had been living in Paris for just four years. They had waited too long. There wasn’t a car or a bicycle left in the city. The husband bought every spare part he could find and built two bikes from scratch. At 5:30 on the morning of June 12, they rode out of Paris with a monkey hidden in the basket.

Hans Reyersbach and his wife, Margarete Waldstein, were artists from Hamburg, but they had met in Rio de Janeiro. Hans had moved there in 1925 after serving in World War I. He sketched and painted, and sold plumbing fixtures up and down the Amazon. Margarete, a photographer, arrived a decade later. If Hans was dreamy and sweet, Margarete was ambitious and unsentimental. They were perfect for each other. They were married in Rio in 1935 and honeymooned in Paris and never got around to leaving—until they pedaled away with the manuscript and art for what would become one of the most popular children’s books of the 20th century.

That first day they rode 30 miles south to Étampes. They could still hear the German shelling. The next day they made it to Acquebouille, another 20 miles south, and slept a fitful night in a barn. Then to Orléans, exhausted, where they squeezed onto a packed train—one of the last. Eleven days and almost 1,000 miles after leaving Paris, they rolled into Lisbon, where they waited months to cross the Atlantic to Brazil. At last they sailed for New York City.

In America, a friend named Grace Hogarth had just been hired as a children’s book editor at Houghton Mifflin. She saw a kind of bravery in the book’s optimism. “It took courage to print and publish colorful books in a gray wartime world,” she later recalled. She signed them to a four-book contract, and “Fifi,” their primate protagonist, was renamed “George.”

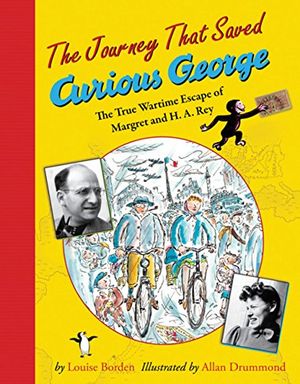

You can find the day-to-day, even hour-by-hour notations of their escape in Hans’ meticulous notebooks, saved at the University of Southern Mississippi, in a collection that bears the couple’s pen names: H. A. and Margret Rey. The trove was the basis for Louise Borden’s book The Journey That Saved Curious George, reissued this year, and has been a gold mine for documentary filmmaker Ema Ryan Yamazaki, whose film about the Reys and Curious George is to arrive on the festival circuit next year. “It was because of who they were that they were able to make Curious George,” she says.

How much of any author finds its way into a character? Like Margarete and Hans, George rides a bike and dreams of flying. Of escape. Every story in every book is a series of close calls. George needs help and people give it. Like most of us, he doesn’t set out to commit mischief. His curiosity propels him, and he just gets caught up in the gears of circumstance. In that way maybe he reminds parents how children learn and offers a subtle commentary on the slapstick dangers of fate and conformity.

So far 75 million copies of the Curious George books have been sold worldwide in over a dozen languages. But the monkey who escaped the Nazis in a bicycle basket never had a closer call than his very first.

Related Reads

The Journey That Saved George

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Jeff_MacGregor2_thumbnail.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/4f/db/4fdb5372-f973-47b7-8ad9-7f6e4a255121/nov2016_h01_phenom-wr-v2.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Jeff_MacGregor2_thumbnail.png)