Planned Afghan Cultural Center Will Honor Ancient Statues Destroyed by the Taliban

The winning design will memorialize two ancient Buddha statues demolished in 2001

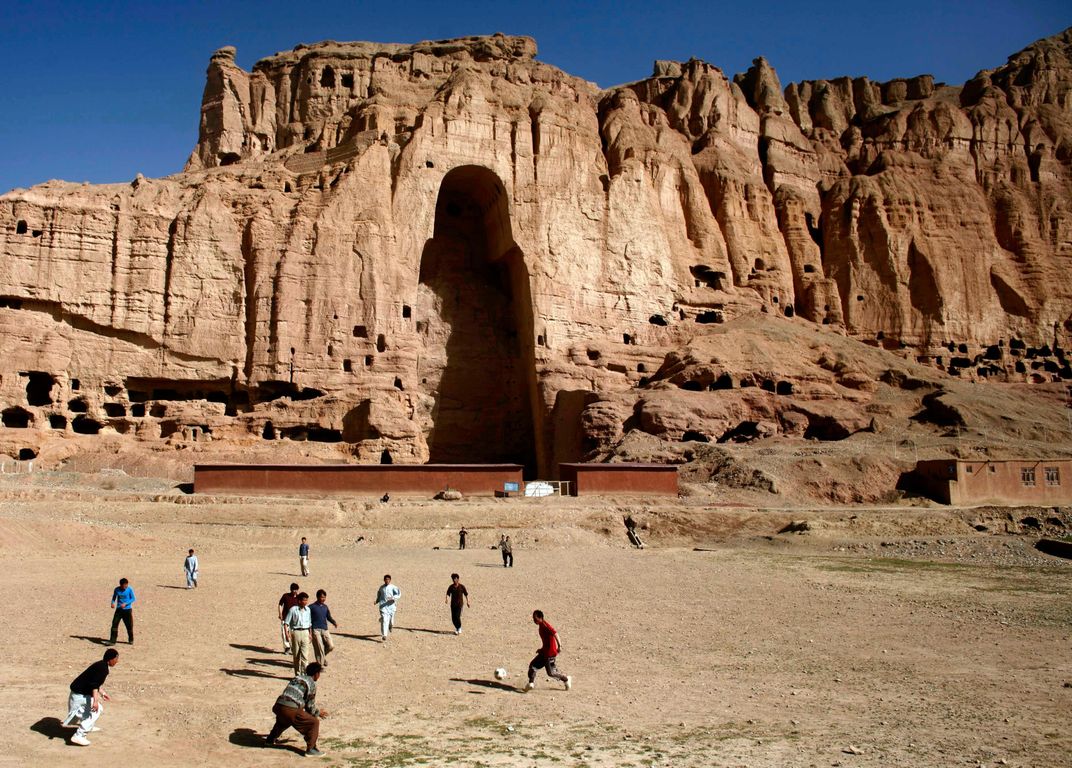

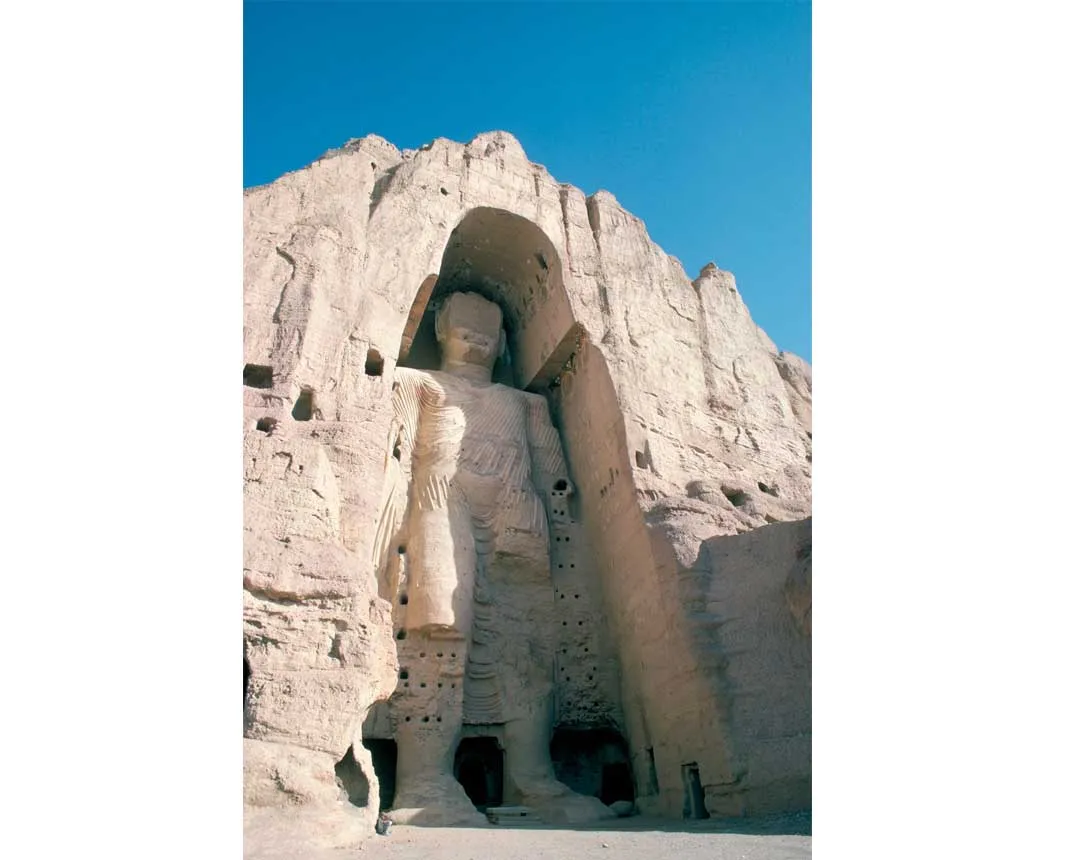

In March 2001, the Taliban destroyed two ancient, colossal Buddha statues that towered above Afghanistan’s Bamiyan Valley. The statues, carved about 1,500 years ago by monks and considered the largest of their kind in the world, were integral not only to Buddhism (one even contained relics from the Buddha himself) but also to local culture. “The statues symbolised Bamiyan,” Mullah Sayed Ahmed-Hussein Hanif told The Guardian, even though locals (now mostly Muslim) “had completely forgotten they were figures of the Buddha,” said Hamid Jalya, head of historical monuments in Bamiyan province, to the news outlet.

Conservators who’ve studied the remains after the blast have been impressed by the degree of artistic skill used 15 centuries ago. Although workers carved the main bodies of the Buddhas from the cliff, they formed the robes that covered them from clay, using a “technically brilliant method of construction.” And as one expert told the Washington Post, “The Buddhas once had an intensely colorful appearance.” Depending on the part of the statue and the era (they were repainted over the years), the forms were dark blue, pink, bright orange, red, white and pale blue.

The spaces that remain after the Taliban’s destruction—two empty niches carved into the cliff face—have since been described as “open wounds,” blemishes, symbols of violence and instability. Their destruction caused a worldwide outcry.

For more than a decade, a controversy lingered over whether or not to rebuild the statues. Although some archeologists wanted to do so, Unesco’s Venice charter—which says that monumental reconstruction has to be done using the original materials—made that unlikely.

When Unesco finally made moves to honor the loss (they declared the area a World Heritage site in 2003, but took a while deciding what to do), the organization launched a competition for the site, not to rebuild or replicate the Buddhas but to mark their destruction with a larger cultural center. The center is designed to host exhibitions, education and events that will promote “cross-cultural understanding and heritage,” according to Unesco. Festivals, films, drama, music and dance will also fill the space, with the “broader aims of reconciliation, peace-building and economic development” in the country.

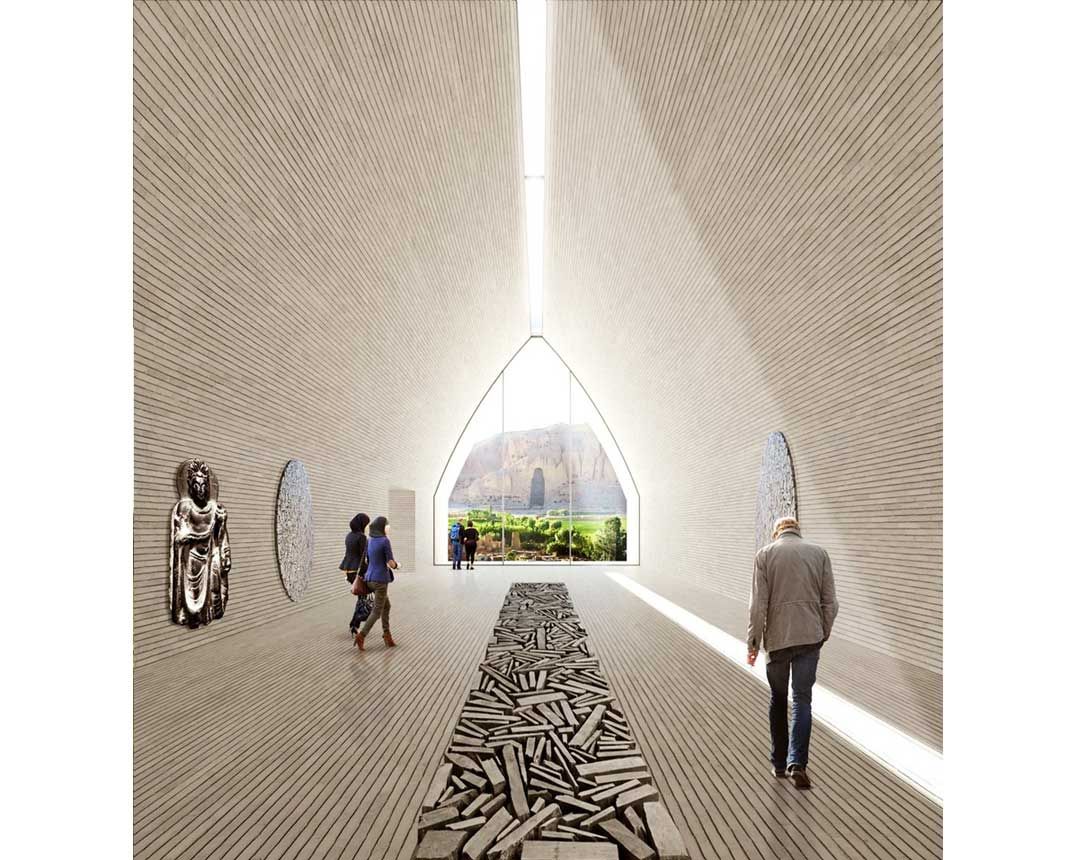

The winning design, announced in late February, came from a small architectural firm in Argentina called M2R, and takes its aesthetic from ancient Buddhist monasteries. As one of the three lead designers, Nahuel Recabarren, told Smithsonian.com: “It was easy to fall into the trap of making a gloomy building that was only about the destruction of the Buddhas. In the end, we decided that we didn’t want to create a building that was a monument for a tragedy but rather one that worked as a meeting place.” The project, he said, “creates multiple interior and exterior spaces for contemplation but also very informal and lively spaces for people to enjoy.”

The design team also didn’t want the Bamiyan Cultural Centre to dominate the landscape and history of the area. Much of recent architecture has become obsessed with image and visibility, Recabarren said, but in this case, “instead of creating an object to be viewed and admired we decided to make a moment of silence: a space where architecture was not an object but rather a place. Our building has a subtle presence because we wanted life, history and people to be the protagonists.”

To that end, the center will be almost entirely underground. Because Buddhist monks carved spaces into the mountain in ancient times, Recabarren said, he and his team wanted to acknowledge and reinterpret that tradition of excavating the natural landscape rather than building structures upon it.

“We are interested in the fact that voids and negative spaces can have an even stronger emotional presence than built objects,” he said.

The team drew inspiration not just from ancient local traditions, but from “the rock-hewn churches in Lalibela, Ethiopia, and the amazing works of the Basque sculptor Eduardo Chillida,” as well as the infrastructure of places like the prehistoric Jordanian city of Petra, much of which was carved out of sandstone cliffs.

And because gardens and open spaces “are a central element of the built environment of Afghanistan,” Recabbaren said, noting that social life in the country often takes place outdoors, his team designed a piazza, or open public area, that overlooks the valley.

The architects are still figuring out a timeline with Unesco, but hope to begin construction next year. Unesco and the Ministry of Information and Culture of Afghanistan are leading the project, with financial support from South Korea, which gave a $5.4 million grant.

You can see the architectural renderings of the new center, as well as images of the Buddhas it commemorates, above.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/michele-lent-hirsch.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/michele-lent-hirsch.jpg)