Home on the Range

A new public television series transplants three American families to the frontier West of 1883, without electricity, running water or visits to the mall

When 9-year-old Logan Patton started getting headaches, it created something of a dilemma for the producers of Frontier House, a six-part series scheduled to begin airing on PBS stations April 29. The problem was that aspirin and other painkillers of choice didn’t exist in 1883, the period created with painstaking accuracy and $3 million by New York public television station Thirteen/WNET and Wall to Wall Television. Still, series producer Simon Shaw wasn’t about to take his zealous quest for authenticity so far as to deny the boy medication. “There’s a point where you just have to relent,” he says.

In May 2001 Shaw recruited three modern families to live in one-room cabins for five months in backcountry Montana—without electricity, ice, running water, telephones or toilet paper. Though Frontier House is dramatic, at times even harrowing, Shaw bristles at any suggestion that the series is a Survivor for eggheads. “Reality-TV programs are game shows. We’re trying to do something more complex,” he says. Shaw helped create the British series The 1900 House, which ran on PBS in 2000. It presented the trials of an initially eager couple who suffered with four of their children through three months of cold baths and gaslit evenings in a retro-furnished Victorian town house.

Frontier House is more ambitious, involving more people subjected to a longer stay in an isolated and rugged setting. By placing 21st-century families in the 19th-century American West, complete with blizzards, nosy bears and week after week of bean dinners, the program explores how settlers once lived and, by comparison, how we live today. “Life in the American West has been greatly romanticized and mythologized,” Shaw says. “We wanted to peel away some of that veneer.”

The producers selected their three homesteading families from more than 5,000 applications. They looked for engaging, sincere, but otherwise ordinary folks with whom viewers could identify. With no prizes or winners, the experience would be its own reward.

The chosen families were supplied with historically correct livestock—low-volume, high-butterfat milk-producing Jersey cows, for example—and provisions such as slab bacon and sorghum. After two weeks of on-camera instruction in the fine points of milking cows and plucking chickens, the participants were carried by wagon train the final ten miles to their destination: a spectacularly telegenic valley 5,700 feet above sea level bordering GallatinNational Forest, north of YellowstoneNational Park.

The families lived in log cabins, each situated on a 160-acre parcel in the creek-fed valley. From one homestead to the next was a ten-minute walk.

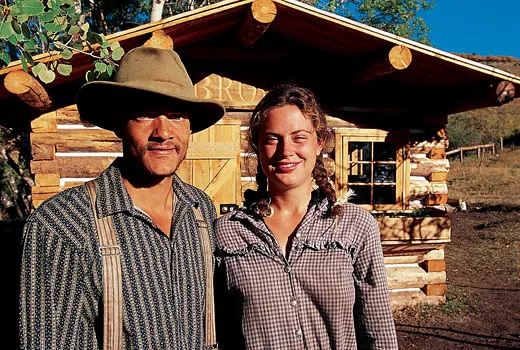

At the head of the valley one day in September, some 20 weeks into the 22 weeks of production, smoke curls from the chimney of the log cabin home of newlyweds Nate and Kristen Brooks, both 28, of Boston. The two are seasoned wilderness hikers. Nate, who was raised on a farm in California, has worked as a college activities coordinator; Kristen is a social worker. Though they’ve lived together for years, she honored 1883 propriety by not arriving in the valley until their July wedding day. Nate’s companion for the early days of the program was his father, Rudy, a retired corrections officer.

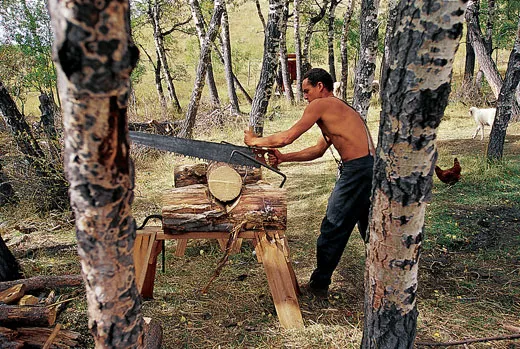

“When my father and I came up, there was nothing here but a pasture and a pile of logs,” says Nate, wearing filthy jeans and a scraggly black beard. The two men lived in a tent—weathering freezing rain, hail and a nine-inch mid-June snowfall—as they notched and hoisted 300-pound logs with ropes and old-fashioned hand tools. (The other two families were provided with at least partly built cabins.) “My father is 68 years old, but he took on the challenge of being out here for six weeks without the comforts of his normal golf and bowling life,” says Nate. Working under the tutelage of log cabin specialist Bernie Weisgerber, father and son finished making the cabin habitable a day before Kristen’s arrival. (After the wedding Rudy flew home to California, where he became reacquainted with his wife, bowling ball and golf clubs.)

“I’m in the middle of goat cheese production,” says Kristen, in granny boots and braids tied in twine. “I hadn’t ever milked an animal before I got here.” By law, homesteaders needed a permanent dwelling, and Kristen has done her part. She proudly points to a window she helped install.

Passed in 1862 to spur settlement of the West, the Homestead Act invited any U.S. citizen to file a claim for 160 acres of public land. If you “proved up”—occupied and farmed the homestead for five years—the land was yours. Nearly two million people, including many a tenderfoot, filed land claims over the act’s 124 years (Alaska was the last state in which the act operated). But working a homestead was an endurance test that many settlers failed; just 40 percent of homesteaders lasted the five years.

It’s still a test. “Without modern conveniences, it takes me five hours to make breakfast and lunch and then clean up,” Kristen says. “It’s all I do.” (In the 1880s homesteaders typically ate off unwashed dishes, saving both time and water.) Divvying up the chores, Nate took on chopping and plowing, and Kristen became the cook. “It’s kind of fun now, because I’ve embraced this role that I normally loathe,” Kristen says. But it was hard in the beginning. “Nate could point to the cabin he built, the garden he planted, his chicken coop. But what could I show?” “When she’s done with a whole day of work,” says Nate, “and we’ve eaten the food and washed the dishes, things look exactly the same as the day before.” Kristen couldn’t even vent for the cameras. “The film crew would say, ‘Oh, we’ve already done frustration.’”

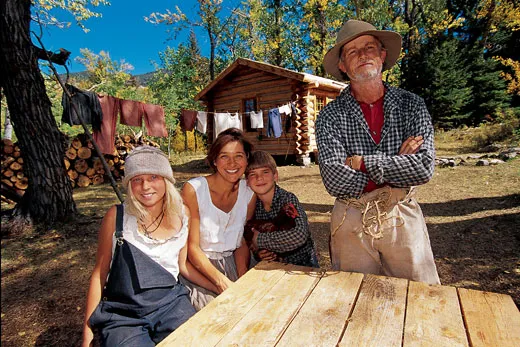

Down the valley, Karen Glenn, a 36-year-old Tennessean, has to cook constantly for her family of four: her husband, Mark, 45, and two children from a previous marriage, Erinn, 12, and Logan Patton, 9. Outgoing, feisty and cheerfully talkative, Karen is baking bread. When not cooking, she scrubs clothes on a washboard. She works as she talks. “In the 21st century, we’re so into being clean,” she says in a twangy drawl, ignoring buzzing houseflies. “We keep our bodies clean, our clothes clean, our houses clean. Here, we bathe only twice a week. But we have much less trash because we reuse everything.” The Glenns even dry the peels from precious store-bought lemons to add to tea, then later chew on the tea-sweetened rinds. Empty tin cans serve as measuring cups, candle reflectors, stove racks, lunch pails and extra cooking pots. Karen uses tin can lids as mouse guards on a cord strung across the cabin for hanging grain sacks and ham shoulders. Tin can labels are used as writing paper.

A can of peaches packed in syrup is a rare treat. “The kids were arguing the other day over who would drink the leftover syrup. I said, ‘None of you can. We’ll save it and make jelly.’” The family consumes a fraction of the sugar that it did before. “One of the kids was saying the canned peaches tasted so sweet, why don’t we buy these back home? I said, ‘Honey, we’ve got cans of these back home, but you guys never wanted to eat them.’”

Though her own father was born in a log cabin, the life Karen leads back home in Tennessee—coaching soccer and working as a nurse—is thoroughly middle class. There, the Glenns race from jobs to games to fast-food joints in the family SUV, which features a backseat TV. Here, their only store is a tiny log cabin stocked by the production team with period produce and dry goods. The store is far enough away—a ten-mile trek over windswept ridges—to discourage impulse buys. Erinn and Logan make the trip riding the same horse. “Going camping in an RV just seems so frivolous now,” Karen says.

Erinn, a blonde seventh grader with a newfound affinity for livestock, will never watch Little House on the Prairie with the same acceptance she once did. “I always wanted to be Laura,” she says. Now that she is Laura, in effect, Erinn says the scripts need work. “Laura’s never dirty, and you never see her milking a cow. Their biscuits are never burnt, and they never cuss at the stove, and they’re never sad at dinner. Their store’s right down the street, which isn’t right, and she’d walk in and say, ‘Can I have some candy?’” Erinn giggles indignantly. Candy is an indulgence to be savored. She says she makes butterscotch last a good seven minutes on her tongue.

“I make mine last about a year,” says Logan. Erinn adds: “I sit there and go ‘Mmmm.’ Back home, I’d just chomp them up.”

Karen’s husband, Mark, who has been scything hay, walks up to the cabin and sits down. An admitted McDonald’s junkie, Mark arrived with 183 pounds distributed on a six-foot frame but didn’t consider himself overweight. After almost five months, he’s lost nearly 40 pounds and needs suspenders or a rope belt to hold up his baggy pants. He takes in plenty of calories, what with all the biscuits, bacon, and eggs fried in lard that Karen serves up. But he also burns energy like a furnace. Executive producer Beth Hoppe jokes about publishing The Frontier House Diet.

Mark, an introspective and soft-spoken man, quit his job teaching at a community college to come out here. “The work’s been twice as hard as I thought it was going to be, but at the same time I’ve never been more relaxed in my life,” he says. Mark has come to regard the film crew, with their fluorescent Tshirts and designer water, as eccentric neighbors: he’s happy to see them arrive, happier to see them leave. More than the other participants, he has found himself adapting heart and soul to frontier life. He even considered staying on alone after the TV production closed down. “This experience has truly changed me,” he says simply.

At the low end of the valley is the Clune family of Los Angeles. Gordon, 41, runs his own aerospace-manufacturing firm, and his wife, Adrienne, 40, does charity work. Here, they share the cabin with their daughter, Aine (“ahnya”) and niece Tracy Clune, both 15, and their sons Justin, 13, and Conor, 9. “I had always romanticized the 19th century,” Adrienne says as she spoons chokecherry syrup into jelly jars from a large copper pot on the woodstove. “I’ve always loved the clothes especially.” Like the other women, Adrienne, a slender, fine-featured woman, was given three custom-made period outfits. The Sunday-best dress came with so many undergarments, from bloomers to bustle pads, that the full nine-layer ensemble weighs 12 pounds.

But food was not so bountiful. After initial supplies ran low, “We actually went hungry the first five weeks,” she says, describing beans and cornmeal pancakes night after night. A gourmet cook, Adrienne wasn’t about to extend her coffee with ground peas or to make “pumpkin” pie using mashed beans and spices, as many an old-time settler did. Deprived of cosmetics, Adrienne has taken to moisturizing her face with cow-udder cream.

Next to her, the girls are doing homework at the table. (All six children attend a one-room school in a converted sheep shed.) Aine and Tracy have tried charcoal in lieu of mascara, though they’ve been warned that in frontier days only showgirls and prostitutes painted their faces.

Conor, a recovering TV addict, bursts into the cabin with an arrow he’s whittled and a handful of sage grouse feathers he plans to glue to its shaft. His older brother, Justin, shows off the vegetable garden and a huge hay pile where chickens lay their eggs. Child labor was a necessity on the frontier. “It’s happened that a child failed to split firewood,” says Adrienne pointedly but naming no names, “and I couldn’t cook dinner that night.”

The adjustment to frontier life was hardest for the girls. “There’s tons and tons of work to be done,” says Tracy. “There’s not a day you get a break.” Her grimy forearms are covered with scrapes and scabs from stringing barbed wire and carrying firewood. Back in California, her main pastimes were shopping, watching TV and talking on the phone. Her only chores were to bring the dogs in from the yard for the night and take out the garbage. “I never wanted to take out the trash, because we have a really steep driveway. That was hard work for us in the modern world.” Here, Tracy has milked a cow in a driving snowstorm. Month by month, she and Aine have learned to work harder and complain less. “I feel like I’ve grown up a lot here,” she says.

Gordon Clune’s entrepreneurial personality, if not his lifestyle (he hadn’t mowed the lawn in 16 years), suited him to the challenges. Pale and chubby when he arrived, a shirtless Gordon now looks suntanned and trim. “I’m a strong believer in making every day a little better than the day before,” he says. At the spring, where they get water, he lifts a board that serves as a sluice gate, and water flows into a shallow trench he dug. “Before this, we carried 17 buckets of water to the garden every morning,” he says. By cutting down on the water-fetching, he’s had time to dig a root cellar, excavate a swimming hole and build a two-seater outhouse.

He has also found more time to make Gordon’s Chokecherry Cure-All Tonic. Out past a jury-rigged shower, he shows me a large copper still he designed. “It’s just for sniffing purposes, but if I was to have tasted it, it tastes pretty good.” He smiles. “If I was.”

Gordon is proud of his homestead. “Get this,” he says. “I can be watering the garden, digging the root cellar and making moonshine all at the same time. That’s multitasking.” He plans to keep improving things to the very last day of production, just over a week away. “In five years,” he says, “I could have this place really wired.”

Because all three families find themselves hard-pressed to live entirely off the land, they barter among themselves—trading goat cheese for pies, or firewood for the loan of a horse. Storekeeper Hop Sing Yin, portrayed on camera by Butte rocket scientist and local history buff Ying-Ming Lee, handles cash transactions. He has agreed to buy 25 bottles of Gordon’s cure-all tonic for $25—equivalent to two months’ pay for an 1883 ranch hand. The program’s researchers combed probate records, newspaper ads and rural shop ledgers from Montana Territory in the 1880s to learn what things cost then. A pitchfork was $1; a dozen needles, eight cents. When tendinitis turned Karen Glenn’s fingers numb, a local doctor made a house call. “We billed her for the doctor’s travel at a dollar a mile, which is what it would have cost back then,” says producer Simon Shaw. “Unfortunately, the doctor was 18 miles away.” The bill wiped out a fourth of the Glenns’ savings and forced Karen to take in laundry from “miners” at 20 cents a pound. One piece of clothing was stained with melted chocolate that production assistants had rubbed into it for a really grubby look. Karen recognized the aroma while scrubbing at her washboard. Her eyes filled with tears.

Despite the Frontier House deprivations, no one was eager to pack up when filming ended in October. And when recontacted in March, the participants all claimed that the experiment had changed them.

“It was a whole lot easier adjusting to less out there than it was coming back here and adjusting to more,” says Karen Glenn from Tennessee, where the couple decided to separate after they returned. “There’s so much noise and traffic and lights on everywhere. It’s overwhelming.” Once home, she got rid of her car phone, her beeper and the premium cable-TV package, all once family necessities. And she doesn’t use her dishwasher anymore. “Doing dishes in hot running water by hand is so nice now. It’s my time to reflect, which I never used to do before.”

In California, Adrienne Clune, too, has slowed her once-hectic pace. She says she drives less and shops less. Before the show, she and Gordon bought a new, 7,500-square-foot house in Malibu. They now say they regret it. “If we had waited till we got back from the frontier, we probably would have bought a much smaller, cozier house,” Adrienne says. She keenly misses the family intimacy imposed by their 600- square-foot cabin. Moving into the new house, she found the experience of unpacking box after box of household items sickening. “If a burglar had run off with most of our possessions while we had them in storage, I wouldn’t have cared,” she says. “They’re just things.”

Though between jobs, Kristen Brooks says she’s gained newfound confidence. “I feel like I could do anything now.” Like the Glenns, Nate and Kristen have stopped using a dishwasher. They even question the necessity of flush toilets. But Kristen draws the line at giving up her washing machine. “That,” she says, “is God’s gift to the world.”