Over 99 percent of all species that have ever existed are extinct. Some are celebrated, like the ferociously famous dinosaur Tyrannosaurus rex. Others, like an ancient set of stacked cones called Cloudina, are more obscure. But as life has continued spinning off more “endless forms most beautiful and most wonderful,” extinction has acted as the flipside to evolution as our planet’s biota continually reshapes itself.

John Whitfield’s Lost Animals: Extinct, Endangered, and Rediscovered Species from Smithsonian Books is a tribute to the vast menagerie of long-gone creatures, from pancake-like organisms that seem to defy classification to the endangered Bermuda petrel, a bird that may soon join Whitfield’s list. From this gorgeously illustrated compendium, here are ten creatures to be found on its pages, many of which are unlike any species alive today.

Lost Animals: Extinct, Endangered, and Rediscovered Species

Lost Animals brings back to life some of the most charismatic creatures to inhabit the planet. It captures the imagination with more than 200 incredible photographs, artworks of fossils, and scientific drawings of charming creatures like dodos, paraceratherium (the largest land mammal), spinosaurus (the biggest carnivorous dinosaur), placeoderm fishes (the sharks of their day), and more.

A Four-Foot-Wide Frilly Rug

More than 560 million years ago, in the days of Dickinsonia, animal life was new. And strange. In life, Whitfield writes, Dickinsonia resembles “a frilly rug” that could reach over four feet across. These creatures were also successful, given how often they’re found among Australia’s Ediacara Hills. But what were they? A few clues—such as preserved remnants of biological compounds—indicate that Dickinsonia was indeed an early animal, but scientists are still scratching their heads as to where this ridged pancake fits in the Tree of Life.

One of the World’s First Backbones

At first glance, Pikaia might seem like little more than a prehistoric squiggle. The tiny animal, shorter than your pinkie, might not appear to be much more than a tube with a dark streak running along its back. But that streak is important—it’s a notochord, or a precursor of our spinal column that marks Pikaia as one of the earliest relatives of vertebrates. “Pikaia had a fin on its back and could probably swim by flexing its body like an eel,” Whitfield writes, which would have allowed our ancient relative to swim away from the more numerous invertebrates with grasping limbs and compound eyes that dominated the seas 508 million years ago.

A Clawed-Trunk For a Nose

When Opabinia was first revealed to paleontologists at a scientific conference, Whitfield writes, the “audience burst out laughing.” What other reaction could there be to a tiny creature with a segmented body of plates, five eyes on mushroom-like stalks, and a proboscis ending in a kind of claw? This animal, an ancient and strange relative of today’s arthropods, was certainly one of the odder inhabitants of the 508 million-year-old Burgess Shale. In fact, paleontologists still puzzle over how this animal lived. Perhaps the position of the hose-like appendage beneath the body, Whitfield speculates, indicates that Opabinia “must have eaten like an elephant snacking on peanuts.”

Ferocious Chomper

Imagine a great white shark with a staple remover for a mouth and you have some idea of what Dunkleosteus looked like. During its heyday, about 420 million years ago, this armored fish was among the biggest and fiercest meat-eaters in the seas. Instead of chomping with teeth, like sharks, this predator sliced through other armored fish with immense jaws made of sharpened bony plates. Based on calculations of the animal’s bite, Whitfield notes, Dunkleosteus could have bit down on prey with a bite exerting over 1,100 pounds of force.

Humongous Dragonfly

Getting buzzed by big dragonflies is a common summertime experience. Now imagine the same happening with a similar insect with a wingspan over two feet across. That’s the size of Meganeura, Whitfield points out, one of the largest members of a dragonfly-like family called griffinflies that thrived around 300 million years ago. Increased oxygen, making up a greater percentage of the atmosphere than today, allowed insects to breath more efficiently and may have even altered air pressure to give flying arthropods like Meganeura a bit more lift with each flap of their wings.

Turtle From the Dawn of Time

Turtles are an incredibly ancient group of reptiles. The earliest of their kind evolved 260 million years ago, and by 210 million years ago Proganochelys looked very much like its modern counterparts. “Proganochelys had a fully-developed shell, covering both its back and its belly, as well as a beak,” Whitfield writes. But this ancient reptile still had some traits not seen among its living relatives, like a spiked-covered club tail that would have helped this slow mover defend itself.

Toothy Sea Creature

During the great Age of Reptiles when dinosaurs ruled the land, there were also fantastic saurian in the seas. Among the largest was Liopleurodon, a 23-foot-long marine reptile that swam the Jurassic seas more than 145 million years ago. While many members of the plesiosaur family had small heads and long necks, Liopleurodon belonged to a subgroup with big heads and short necks that allowed the carnivore to hunt large prey. “Armed with 4-inch teeth and capable of biting with incredible force,” Whitfield writes, “it would have been able to kill whatever it grabbed between its jaws.”

Confusing Set of Tusks

Today’s elephants have tusks that jut straight out from their jaws. But not all their ancient relatives had the same arrangement. Around 20 million years ago there lived a prehistoric pachyderm named Deinotherium with twin, curved tusks curving down from the jaw. Precisely what the elephant used these tusks for isn’t clear. One early—and fanciful idea—is that Deinotherium used them to anchor itself to riverbanks while sleeping. Paleontologists may yet discover the real answer.

Mysterious Carnivorous Beast

Among all the carnivorous mammals that have ever lived, Andrewsarchus may have been the largest. The trouble is that this meat-eating beast is only known from a skull and a foot, Whitfield says, with no other fossils coming to light in nearly a century. Still, based on related animals, it seems that Andrewsarchus was about the size of a rhino and took down prey with massive jaws, acting more like an enormous wolf than a cat. Hopefully more fossils will fill in what we know of these 45-million-year-old enigmas.

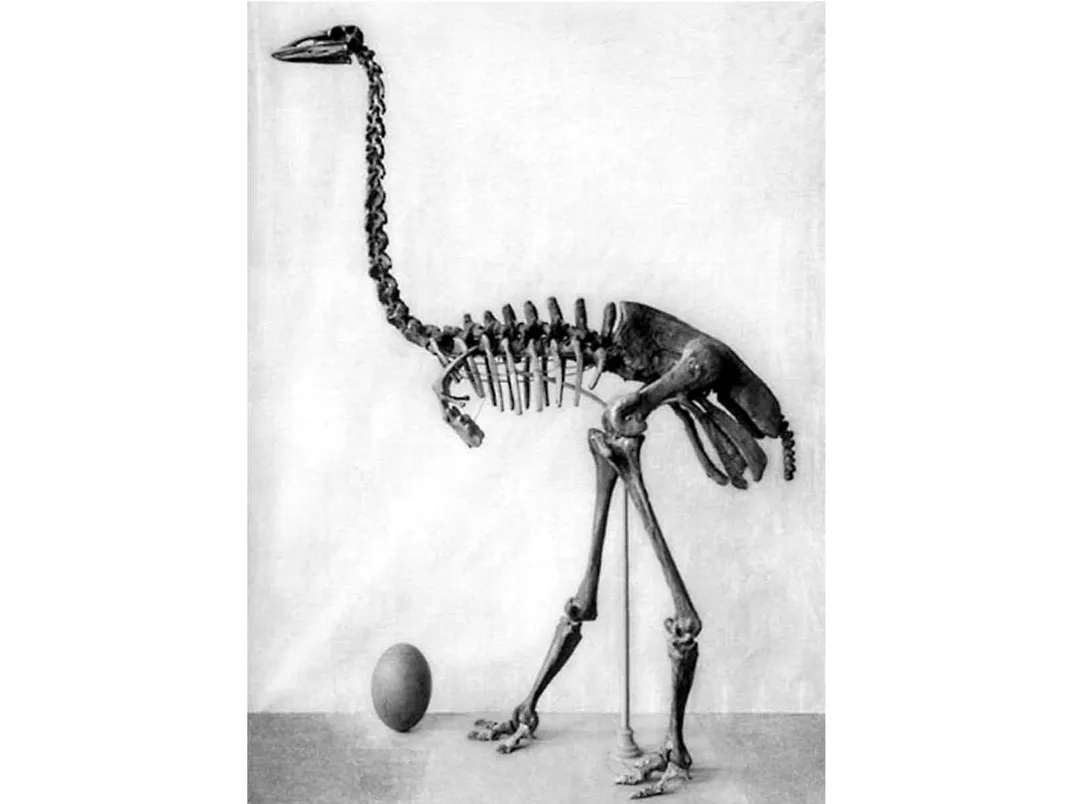

Hatched from Huge Eggs

Not all giant and impressive creatures are from the ancient past. Some lived relatively recently. Up until about 1,000 years ago, Whitfield notes, various species of elephant birds lived on Madagascar. On an island free from large carnivores, some of these flightless birds got to be over 10 feet tall and weighed more than 140 pounds. Their eggs were huge, larger than that of even the biggest non-avian dinosaurs. And their absence can still be felt. Elephant birds were herbivores and helped keep the ecosystem vibrant by spreading seeds through their droppings. Their disappearance changed the nature of the place they lived, just as every vanished species has.

A Note to our Readers

Smithsonian magazine participates in affiliate link advertising programs. If you purchase an item through these links, we receive a commission.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/3e/1e/3e1e4781-46dc-4998-8671-02f9856dd02a/longform_mobile.jpg)

:focal(980x323:981x324)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/c4/6d/c46d0794-f557-4d54-8c20-161facbd643a/testing4.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/RileyBlack.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/RileyBlack.png)