Rescuing Jorge Prelorán’s Films From Storage And Time

The Smithsonian’s Film Archives is reintroducing the world to the influential work of the Argentine-American filmmaker

Last May, a Smithsonian researcher traveled to a farming village in Argentina, where documentary filmmaker Jorge Prelorán filmed a movie four decades ago. The researcher brought with him a copy of the film, the only one in existence. No one from the village had ever seen the film, Valle Fértil, but 500 people showed up to its screening at a local gymnasium. Among the crowd were two people who appeared in the film, as well as the children and grandchildren of other people on screen. Chris Moore, the researcher, says many of them had tears in their eyes.

Behind the mission to reintroduce the world to Prelorán's work is the team at the Human Studies Film Archives, part of the anthropology department at the Smithsonian’s National Museum of Natural History. The Archives launched an online hub for its Prelorán project, which has involved preserving his films and screening them around the world. Following the event in Argentina and screenings in Chile last month, Prelorán’s restored Valle Fértil shows for the first time in the United States on December 4 at the Society for Visual Anthropology Film Festival in Washington, D.C. An exclusive clip from the preserved film appears above.

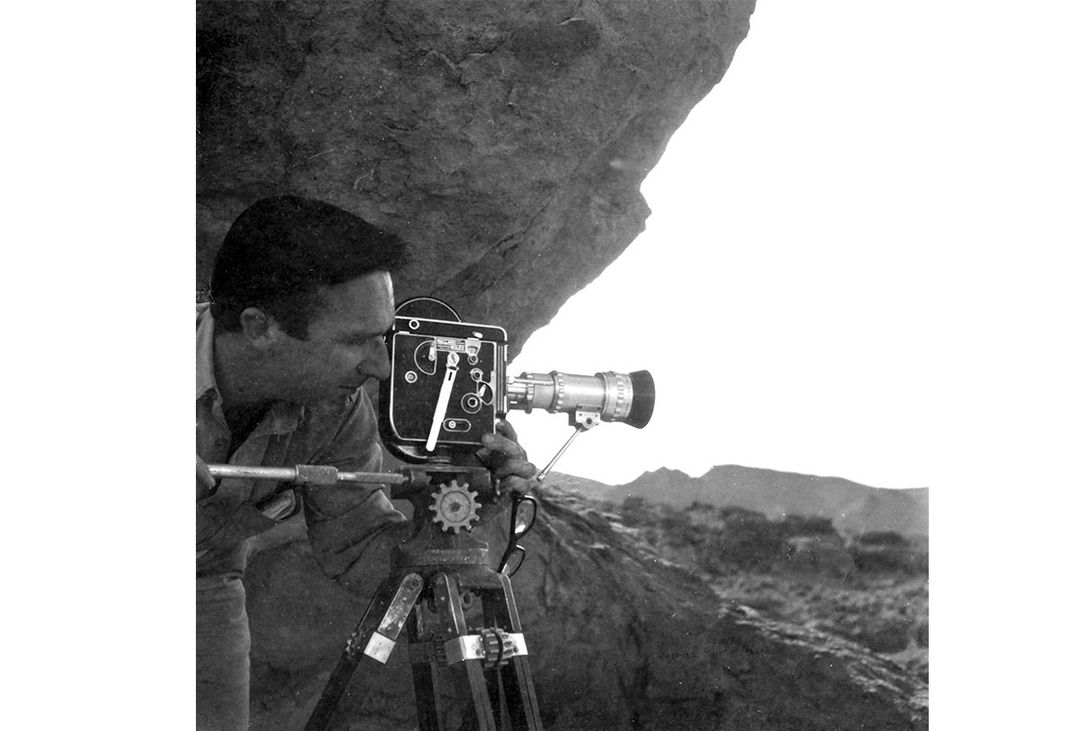

Before his death in 2009, the Argentine-American filmmaker made more than 60 films, some of which have only one remaining print. Once a film student at U.C.L.A., Prelorán took to documentary film in the early 1960s, at a time of renewed interest in the medium, thanks to the cheaper, lighter-weight equipment. “This was a period when there was a lot of excitement about the possibility of anthropological films being used for teaching,” says archives director Jake Homiak. “Prelorán’s films are nested in that same area.”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/80/c2/80c2390f-805c-4c56-807e-1c078f7f7c3a/2.jpg)

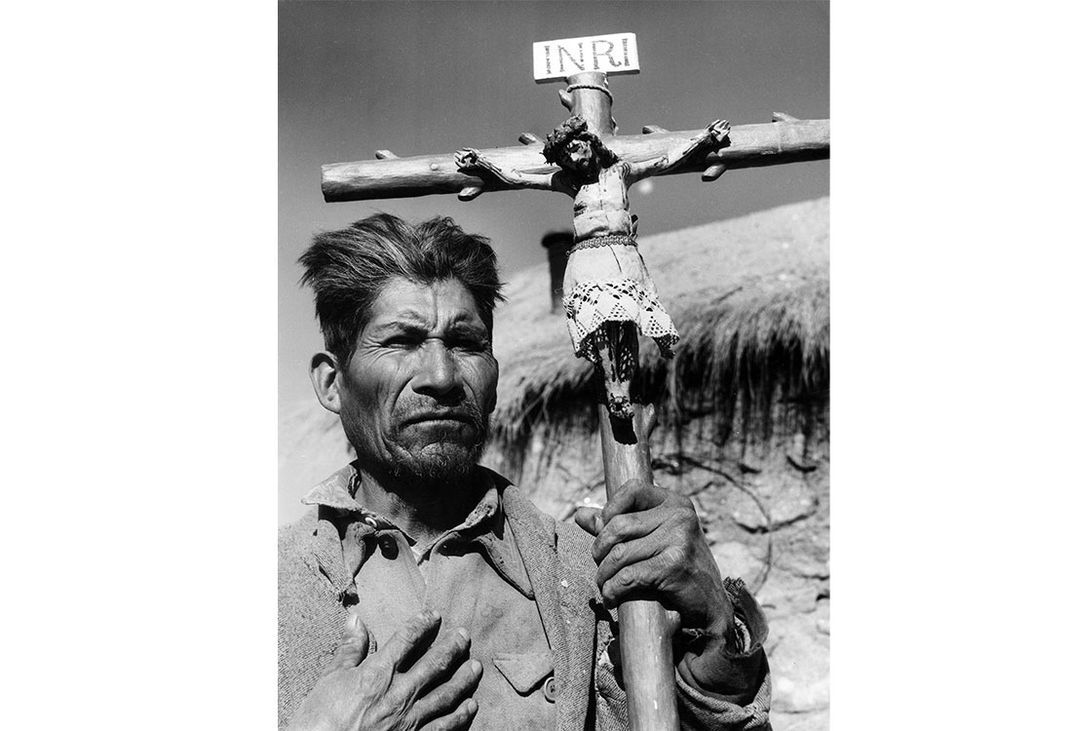

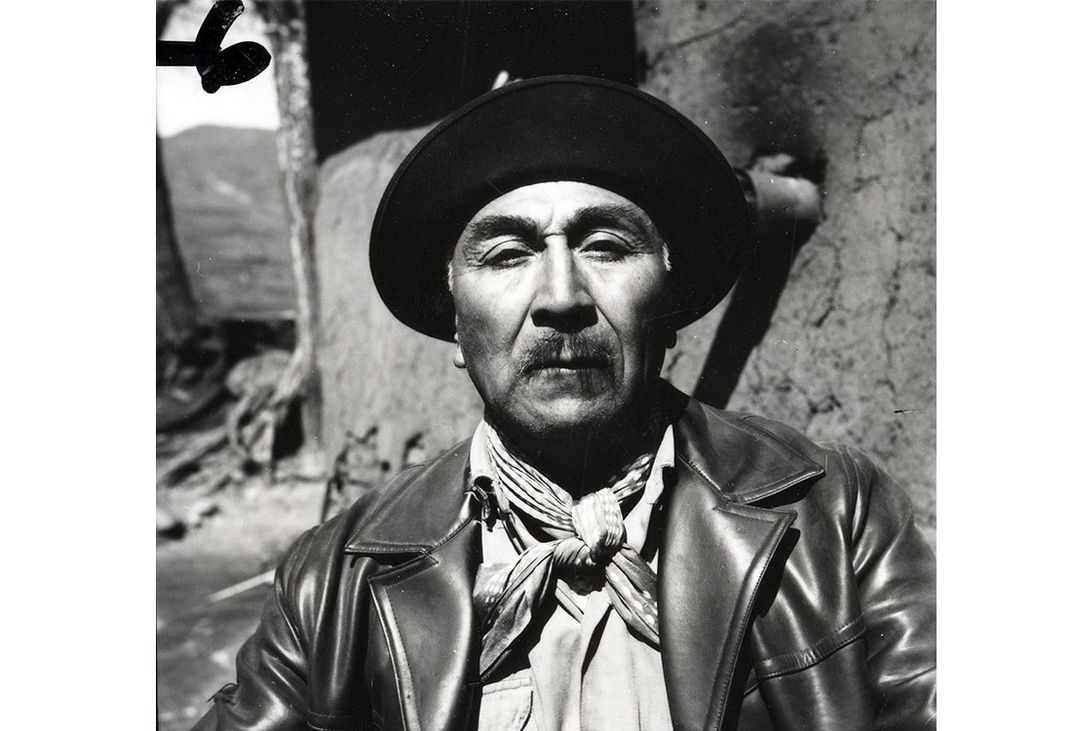

At first, the filmmaker took on science subjects, but it wasn’t long before he shifted to more humanistic stories. “He fell in love with the cultures, the people who lived in very remote areas of Argentina,” says his wife, Mabel Prelorán, who lives in Los Angeles. “To him, it was a revelation to see the struggles of these people, the suffering.”

Life as a filmmaker in Argentina wasn't easy. Following the disapeparance of some friends and a family member, Prelorán and his wife decided to leave Argentina. But fearing the military regime, the filmmaker did not want to travel with some of his more political work, and so he asked friends to hide the film reels. The friends buried the reels in a garden, where they remained for a long time until Prelorán's sister-in-law eventually brought them to the filmmaker in Los Angles. “Jorge put in those films all his life,” his wife says.

Unlike other documentary filmmakers, Prelorán didn’t treat his subjects as foreign. In one of the most celebrated documentary films of all time, Nanook of the North, for example, filmmaker Robert Flaherty depicted his Inuit subject as an exotic character to be observed. Prelorán, on the other hand, spent time getting to know his subjects. “He kept in contact with people until the people died. They became part of our extended family,” Mabel Prelorán says about her husband’s subjects.

The idea to donate his life work’s to the Smithsonian came around 2005, when Prelorán heard that his film collector friend had recently donated. So he contacted the Smithsonian, and archivist Karma Foley traveled to Los Angeles to collect the materials. Foley spent several days organizing the prints, which the filmmaker had kept in zip-lock bags in his finished attic. At the time, Prelorán was undergoing chemotherapy. “He was being very reflective, thinking about his legacy,” Foley says.

Once the materials arrived at the Archives, archivist Pam Wintle says, “We immediately launched a project to begin to preserve the film.” That effort involved doing photochemical restoration and adding English subtitles.

“Very few people actually got to see his films,” says Smithsonian Fellow Chris Moore, who screened the films in Argentina and Chile. “People generally don’t know very much about who he is, but this is a good first step.”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/MAx2.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/MAx2.jpg)