How Nylon Stockings Changed the World

The quest to replace natural silk led to the very first fully synthetic fiber and revolutionized the products we depend on

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/b9/c2/b9c2a821-4db6-4fa2-96ae-6fc04568791c/nmah-2005-16765r.jpg)

Major technological innovations such as gunpowder, GPS and freeze dried ice cream are more likely to be credited to military research than to women’s undergarments, but one humble pair of lady’s stockings in the Smithsonian collections represents nothing less than the dawn of a new age—the age of synthetics.

Woven of a completely new material, the experimental stockings held in the collections of the National Museum of American History were made in 1937 to test the viability of the first man made fiber developed entirely in a laboratory. Nylon was touted as having the strength of steel and the sheerness of cobwebs. Not that women were jonesing for the feel of steel or cobwebs around their legs, but the properties of nylon promised a replacement for the luxurious, but oh so delicate silk that was prone to snag and run.

An essential part of every woman’s wardrobe, stockings provided the perfect vehicle for DuPont, the company responsible for the invention of nylon, to introduce their new product with glamorous aplomb. Nylon stockings made their grand debut in a splashy display at the 1939 World’s Fair in New York. By the time the stockings were released for sale to the public on May 15, 1940 demand was so high that women flocked to stores by the thousands. Four million pairs sold out in four days.

In her book Nylon; The Story of a Fashion Revolution, Susannah Handley writes: “Nylon became a household word in less than a year and in all the history of textiles, no other product has enjoyed the immediate, overwhelming public acceptance of DuPont nylon.”

The name may have become synonymous with stockings, but hosiery was merely the market of choice for nylon’s introduction. According the American Chemical Society it was a well calculated decision. They state on their web site:

The decision to focus on hosiery was crucial. It was a limited, premium market. "When you want to develop a new fiber for fabrics you need thousands of pounds," said Crawford Greenewalt, a research supervisor during nylon development who later became company president and CEO. "All we needed to make was a few grams at a time, enough to knit one stocking."

The experimental stockings were manufactured by Union Hosiery Company for Dupont with a cotton seam and a silk welt and toe. They were black because scientists hadn’t yet figured out how to get the material to take flesh-colored dye. One of the other hurdles to be overcome was the fact that nylon distorted when exposed to heat. Developers eventually learned to use that property to their advantage by stretching newly sewn stockings over leg-shaped forms and steaming them. The result was silky smooth, form-fitting hosiery that never needed ironing.

Nylon’s impact on fashion was immediate, but the revolution sparked by the invention of what was originally called fiber-66 rapidly extended its tendrils down through every facet of society. It has given rise to a world of plastics that renders our lives nearly unrecognizable from civilizations of a century ago.

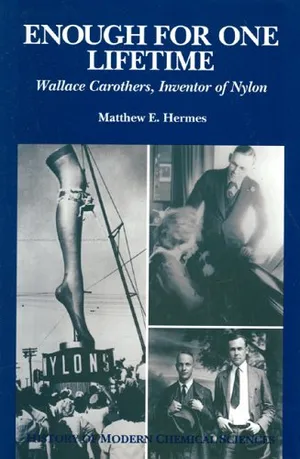

“It had a huge impact,” says Matt Hermes, associate professor at the bioengineering department at Clemson University. He is a former chemist for DuPont who worked with some of the early developers of synthetics and wrote a biography on nylon’s inventor Wallace Caruthers. “There’s a whole series of synthetic materials that indeed came from the base idea that chemists can design and develop a series of materials that had certain properties, and the ability to do it from the most basic molecules.”

There-in lies the true revolution of nylon. Synthetic materials were not completely new. But until the breakthrough of nylon, no useful fibers had ever been synthesized entirely in the laboratory. Semi-synthetics such as Rayon and cellophane were derived from a chemical process that required wood pulp as a basic element. Manufacturers were stuck with the natural properties plant material brought to the table. Rayon for instance was too stiff, ill-fitting and shiny to be embraced as a replacement for real silk, which is, of course, merely the chemical processing of wood pulp in the belly of a silk worm rather than a test tube. Nylon, on the other hand, not only made great stockings, but was manufactured through human manipulation of nothing more than “coal, air and water”—a mantra often repeated by its promoters.

The process, involves heating a specific solution of carbon, oxygen, nitrogen and hydrogen molecules to very high temperature until the molecules begin to hook together in what’s called a long-chain polymer that can be drawn from a beaker on the tip of a stir stick like a string of pearls.

The completely unnatural features of nylon may not play as well in the marketplace today, but in 1940, on the heels of the Great Depression, the ability to dominate the elements through chemistry energized a nation weary of economic and agricultural uncertainty. “One of the largest impacts was not only the generation of the synthetic material era,” says Hermes, “but also the idea that the nation could recover from the economic doldrums that went on year after year during the depression. When new materials began to surface, these were hopeful signs.”

It was a time when industrial chemistry promised to lead humankind into a brighter future. “All around us are the products of modern chemistry,” boasted one promotional film from 1941. “Window shades, draperies, upholstery and furniture, all are made of, or covered with, something that came from a test-tube. . . in this new world of industrial chemistry the horizon is unlimited.”

The modern miracle of that first pair of nylon stockings represented the epitome of human superiority over nature, American ingenuity and a luxurious lifestyle. Perhaps more important, however is that the new material being woven into hosiery promised to release the nation from reliance on Japan for 90 percent of its silk at a time when animosity was reaching a boiling point. In the late 1930s, the U.S. imported four-fifths of the world’s silk. Of that, 75 to 80 percent went into the making of women’s stockings—a $400,000 annual industry (about $6 million in today's dollars). The invention of nylon promised to turn the tables.

By 1942, the significance of that promise was felt in force with the outbreak of World War II. The new and improved stockings women had quickly taken to were wrenched away as nylon was diverted to the making of parachutes (previously made of silk). Nylon was eventually used to make glider tow ropes, aircraft fuel tanks, flak jackets, shoelaces, mosquito netting and hammocks. It was essential to the war effort, and it has been called “the fiber that won the war.”

Suddenly, the only stockings available were those sold before the war or bought on the black market. Women took to wearing “leg make-up” and painting seams down the backs of their legs to give the appearance of wearing proper stockings. According to the Chemical Heritage Foundation, one entrepreneur made $100,000 off of stockings produced from a diverted nylon shipment.

After the war the re-introduction of nylon stockings unleashed consumer madness that would make the Tickle-Me-Elmo craze of the 90s look tame by comparison. During the “nylon riots” of 1945 and ’46 women stood in mile-long lines in hopes of snagging a single pair. In her book Handley writes: “On the occasion when 40,000 people queued up to compete for 13,000 pairs of stockings, the Pittsburgh newspaper reported ‘a good old fashioned hair-pulling, face-scratching fight broke out in the line.’”

Nylon stockings remained the standard in women’s hosiery until 1959 when version 2.0 hit the shelves. Pantyhose—panties and stockings all in one—did away with cumbersome garter belts and allowed the transition to ever higher hemlines. But by the 1980s the glam was wearing off. By the 90s, women looking for comfort and freedom began to go au-natural, leaving their legs bare as often as not. In 2006, the New York Times referred to the hosiery industry as “An Industry that Lost its Footing.”

In the last 30 years sheer pantyhose have done a complete 180, devolving into fashion no-no’s except for sheer black and in offices where dress code prohibits bare legs. The mere mention of pantyhose ruffles some women’s feathers. In 2011, Forbes writer Meghan Casserly blogged they were “oppressive,” “sexist,” “tacky” and “just plain ugly.” She was striking out against one pantyhose manufacturer’s campaign to re-invigorate the market among younger women.

Fashion editor for the Washington Post, Robin Givhan takes a more subdued stance. “I wouldn’t say they’re tacky. They’re just not a part of the conversation; they’re a non-issue in fashion.”

Even at formal affairs, Givhan says bare legs are now the norm. “I think there’s a certain generation of women that feel they’re not properly dressed in a polished way unless they’re wearing them, but I think they’re going the way of the dodo bird,” she says. “I don’t think there is even the slightest chance that they’re coming back.”

No matter, they’ve made their point. Nylon has become an indispensible part of our lives found in everything from luggage and furniture to computers and engine parts. Chemistry and human ambition have transformed the world in which we live.

Nylon: The Story of a Fashion Revolution

Enough for One Lifetime: Wallace Carothers, Inventor of Nylon (History of Modern Chemical Sciences)