Newly Unearthed Mesoamerican Ball Court Offers Insights on Game’s Origins

“This could be the oldest and longest-lived team ball game in the world,” says one archaeologist

:focal(403x281:404x282)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/a3/0a/a30a4ad4-5d58-4d64-bfb7-515ecdf9c84a/maya.jpg)

The ball game pok-ta-pok was nearly ubiquitous in pre-Hispanic Mesoamerica, but today, its origins remain a matter of debate among archaeologists. Though a version of the activity appears in the Maya creation myth, many modern researchers suspect it actually originated near the Gulf Coast. Now, however, a newly discovered pok-ta-pok court nestled in the highlands of Oaxaca, Mexico, is challenging that theory.

The court, found at the Etlatongo archaeological site, dates to between 1400 and 1300 B.C., according to research published in the journal Science Advances. In use for about 175 years, the space is the second-oldest Mesoamerican ball court found to date—the oldest is located in Paso de la Amada and was built around 1650 B.C., reports Science magazine’s Lizzie Wade.

The Etlatongo court dates to a pivotal period in the region’s history, when political and religious factions, trade, and a clear social hierarchy were starting to emerge.

“It’s the period when what we think of [as] Mesoamerican culture begins,” study co-author Salazar Chávez of George Washington University tells Science.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/26/07/2607055b-64e4-487a-90d7-3469f69be4a4/f5large.jpg)

Archaeologist and study co-author Jeffrey Blomster, also of George Washington University, has long made a point of excavating sites in the Mexican highlands, reports Discover magazine’s Leslie Nemo. Because the area lacks temples and a complex infrastructure, other researchers have tended to discount its potential. Blomster began excavating in the highlands in the 1990s; he and Chávez started working together in Oaxaca in 2015.

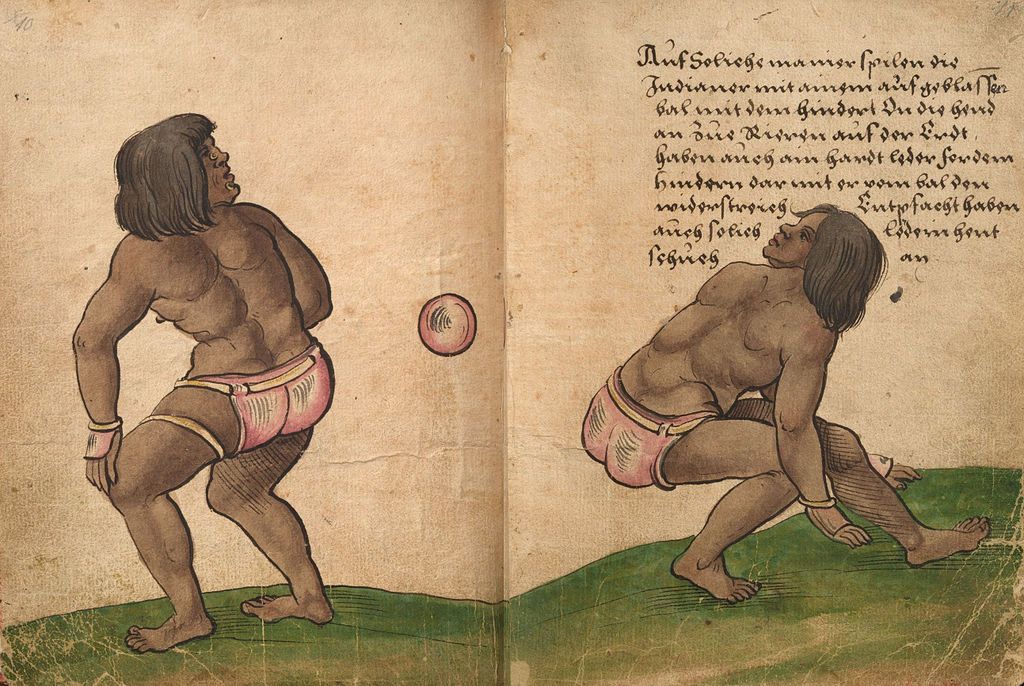

Etlatongo hosted two courts: the original venue and a second larger structure built on top of the first. The space was flanked with rough stone walls that players would bounce a rubber ball off of by hitting it with their hips. The goal was to send the ball soaring onto the opposing team’s side, much like in modern volleyball. Players wore thick, padded belts to protect themselves from the ball, which could weigh up to 16 pounds, but still risked sustaining life-threatening injuries. Behind the walls, the alley-like court was lined with benches for spectators.

The court at Etlatongo is 800 years older than any other court unearthed in the central Mexican highlands, and more than 1,000 years older than any found in Oaxaca. The find suggests that the highlanders who used the court may have contributed to the game’s early rules and customs, instead of just acting like “social copycats” as previously believed, Chávez tells Discover.

“The discovery of a formal ball court [at Etlatongo] … shows that some of the earliest villages and towns in highland Mexico were playing a game comparable to the most prestigious version of the sport known as ullamalitzli some three millennia later by the Aztecs,” Boston University archaeologist David Carballo, who wasn’t involved in the study, tells Bruce Bower at Science News. “This could be the oldest and longest-lived team ball game in the world.”

The researchers found not only the courts, but the remains of a ceremony that would have marked the end of the playing space’s use. (Burned wood from these ceremonies was used to determine the court’s age.) The archaeologists also recovered pottery and figurines of people wearing padded belts.

Annick Daneels, archaeologist at the National Autonomous University of Mexico who wasn’t involved in the research, tells Science magazine that the pottery and figurines are of the Olmec tradition, suggesting the Etlatongo court “could be inspired by Olmec contact.”

But Radford University archaeologist David Anderson, who was also not involved in the study, tells Science that the new find “suggests that the ball game is an extremely old, broad tradition throughout Mesoamerica that doesn’t originate with any one group.”

Over the millennia, the game evolved, gaining political and religious importance as a replacement for war—or as a rigged punishment for prisoners. The stakes could be high. At times, losers were even sacrificed.

Eventually, the walls alongside the court grew taller, and a suspended ring was added to up the ante: If a player threw the ball through the opening, they would either gain bonus points or instantly win the game.

As Erin Blakemore reports for National Geographic, Dominican priest Diego Durán witnessed the game firsthand when he stopped by an Aztec match in 1585. The winner, he wrote, “was honored as a man who had vanquished many and had won a battle.”